Commonwealth Plasticity

Post-COVID Trade Recovery Pathways and Resilience Building

Reforming and Reinforcing Multilateral Trading Systems

The world can not recover from the impact of COVID-19 without an effective rules-based trading system that is both inclusive and sustainable. It will require members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to work in conjunction towards galvanizing multilateral trade to equip the Commonwealth states, as well as the rest of the world should they wish to partake, for any trade issues that may arise. This is by no means an easy feat amidst the geo-political and geo-economic tensions between the US and China together with the rising unilateral trading measures being adopted by WTO member states. These challenges have intensified due to the recent accusations put on the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism, Appellate Body (AB), by the US over its “overreach” and the latter’s subsequent blocking of new appointments to the AB since December of 2019. The WTO, having received complaints regarding its obsolete rulebook for world trade management, is at a critical juncture at which it must refurbish official standards and rules by incorporating new regulations to accommodate the growing trade in digital services and commodities, shifting modes of manufacturing, and the increasingly worrisome phenomenon of climate change and loss of biodiversity. It is equally as important for the WTO to bear in mind that the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are very much linked to the direct and indirect impacts of international trade as mentioned straightforwardly under 7 of the 17 SDG goals, related to hunger, health, well-being, employment, infrastructure, inequality, sustainable use of oceanic resources, and invigorating international partnerships.

The WTO, with a new Director-General taking the helm in March of this year, is mindful of its obligation to update its system as is evident in its undertaking of various proposals and initiatives, including the Canada-led Ottawa Group and Africa Group. In support of the WTO’s determination for reformation, the Commonwealth Trade Ministers, during a meeting in October 2019, renewed their commitment to work collectively and constructively with fellow WTO members in ensuring the prioritisation of disadvantaged members and provide equal access to a platform for all members to express and forward their respective trade-related developmental interests.

This Trade Review offers initiatives that may be applied forthwith as well as long term plans of action required to build a strong and resilient rules-based trading system.

Actions for prompt implementation

The promotion of transparent policies to ensure predictability in world trade is a salient purpose of the WTO; it invokes member states to submit their trade policies for regular review and declare any new domestic policy measures undertaken that may affect international trade whether directly or indirectly. This mechanism must be executed more strictly during times of crisis, to assure disadvantaged members that protectionist policies brought about due to COVID-19 are “temporary, targeted, proportional, and transparent”, by reinforcing discipline on export restrictions and bettering supervision of trade policy responses to the pandemic, particularly in regards to vaccine distribution. In addition to this, the WTO must attempt to adjust intellectual property rules to public health needs to guarantee affordable and equitable vaccine access for the secure movement of goods and people and the gradual opening of global economies. Relaxing domestic regulations for service providers of essential sectors such as health care may also aid post-COVID recovery.

Relatedly, the importance of digital trade, e-commerce and online service delivery in particular, for the continuation of global trade during the pandemic, can not be overemphasised; in acknowledgement of this, members of the WTO must invest in ways to enhance inclusivity by identifying areas of convergence in cyber trade where possible to lessen the digital capability gaps between developed member states and developing, small, and LDC member states. Progress may be optimised through the Aid for Digital Trade initiative and the Trade Facilitation Agreement to also provide pragmatic solutions to all concerns related to effective capacity building.

The preservation of food security is another critical issue that requires immediate attention as it was significantly hampered by the restrictions on, and self-preserving stock holding of, food trade amidst the panic of the pandemic. This has endangered the well-being of the net-importing developing and LDC states reliant on global trade of edible goods to meet their personal needs. Several WTO members have pressed on fellow member states to expedite the process of drafting a permanent solution to public stockholding (PSH) to guarantee food security for the vulnerable should any similar crisis occur in the future. However, some developed and developing member states maintain caution on such programmes and reject the exportation of products benefitting from the PSH, wary that they may do more harm than good by causing trade distortions.

It must be noted that the food security crisis has been an issue even before the pandemic; the rapid overconsumption of global fish stocks is threatening the food security of the coastal small states, Small Island developing states (SIDS) and LDCs. To prevent the irreversible consequences this may entail, WTO members are envisaging disciplinary prohibition of fisheries subsidies that are known to cause overfishing and overcapacity inclusive of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. This may be implemented with partial exclusions for developing and LDC states that rely more on fishing for their economic well-being. Negotiations on fisheries are long overdue and undoubtedly crucial for the international economy and the achievement of the UN SDGs. The WTO should prioritise such negotiations in the upcoming 12th Ministerial Conference considering how these negotiations were launched during the 2001 Doha Ministerial Conference and already missed the deadline set for the WTO’s 11th Ministerial Conference 2017.

Actions for long-term implementation

Of all the prospective actions recommended for WTO reformation, the most pressing matter is the renovation of the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) and WTO AB. When the AB was deemed dysfunctional by the US government in 2019, the WTO was left with no credible and binding mechanism for the enforcement of settlements. All parties involved in disputes after the disbandment of the AB side-stepped the alternate settlement mechanisms offered by the WTO, deeming them secondary and insignificant, leaving losing parties with no choice but to lodge their appeals “into the void”. Even the attempts of several WTO members, inclusive of some Commonwealth states, to instate the Multiparty Interim Appeal Arbitration Agreement, a replica of the AB’s two-tier appeal mechanism, did not succeed in garnering adequate legitimacy. The WTO is advised to utilise the growing exigency amongst WTO member states for its reform by urging them to undertake a more proactive role to either reinstate a revised WTO AB or reach a consensus on a new binding mechanism to be enforced on all members.

Another time-sensitive dilemma is the increasingly threatening repercussions of climate change, a growing number of natural disasters, and irreversible biodiversity loss. This imposes a great burden on the international community to unite in their efforts for greater cohesiveness and “mutual supportiveness” via collaboration between multilateral trade and environment regimes on climate change and sustainability, areas the WTO does not yet have any particular provisions for. WTO members, frustrated by the lack of a proper forum, have rerouted these concerns to WTO disputes on energy, more specifically renewable energy. Member states including Canada, the US, and the European Union (EU) countries, are considering utilising border carbon adjustment mechanisms and subjecting them to WTO rules and procedures as a multilateral means to tackle climate change. These types of initiatives, if successful, could have a major impact on international trade and the investment landscape for developing countries that may be required to compose more integrated climate change investment plans. This will be particularly challenging for smaller developing states.

Fortunately, discussions on the restructuring of international trade to promote environmental sustainability have been pushed to the fore of the MC12 by 53 WTO members, including Commonwealth states, to mutually agree upon and set timelines for “deliverables” by the time of the MC12 and beyond. The WTO members are also in talks for advanced multilateral collaboration on promoting trade in environmental goods and services, investment in green infrastructure and technologies, and the cancellation of fossil fuel subsidies. Branching off of this, an informal platform involving multiple Commonwealth states endeavours to discuss viable solutions for plastic pollution by discouraging trade in plastic products. Furthermore, the UK is set to be the chairing state for the G7 of industrialised nations as well as the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which is a great opportunity for Commonwealth leadership in the advocation of greener trade-led post-pandemic recovery and greater support for small vulnerable WTO member states.

Improved support measures for LDCs and recent LDC-graduates

The pandemic has hindered the progress of LDCs on the cusp of graduation from the category; Bangladesh was set to graduate after Vanuatu succeeded in doing so by December 2020, but this has been pushed back a further 2 years to allow recovery from the pandemic whilst the Solomon Islands remains determined to graduate by 2024, though with the long term ramifications of the pandemic, this remains unclear. COVID-19’s exacerbation of the LDC economies’ existing vulnerabilities has created a “resilience gap” that will require double the efforts to effectively bridge. Initiatives must hence prioritise the expansion of productive capabilities in higher-productive sectors and promotion of higher value-added activities that will bring about the structural reformation of their economies built for resilience against future economic shocks. Additionally, as comprehensively discussed in Chapter 2, Commonwealth LDCs also face a dearth of digital literacy and access to digital technologies that may significantly hamper future trade prospects.

Multilateralism may potentially play a crucial supporting role for these LDCs provided they can give due consideration to their special requirements as was discussed in Chapter 4 which also emphasised just how much work LDCs have cut out for them in regards to progress in debt sustainability and improved access to financing. The upcoming decade will be the defining timeframe for their future; the previous decade, which ended in 2020 with the failure to meet the goals of the Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA), was an essential reality check plus motivation for a new and revitalised commitment for the LDCs as well as the international community on the need to support these states. The Fifth UN Conference on LDCs, scheduled for January 2022, aims to work towards instating added international support actions to strengthen LDC relations with development partner states. LDC countries have requested the WTO to generate a “smooth transition” mechanism for LDC graduation that will enable them to work towards upgrading whilst retaining flexibilities granted to them for an extra 12 years after their graduation.

Another development area for trade recovery is capacity building for LDCs that maximises the benefits of duty-free market access for various exports to developed economies such as Australia, Canada, the EU-27, the US, and the UK and also notable developing countries including Singapore, China, and India, the latter two of which are established key drivers for global recovery in 2021. Whilst developed economies offer LDCs favourable incentives to maximise the WTO services waiver for export diversification, the utilisation of this avenue is rather low due to the absence of adequate capacity building infrastructure. For LDCs to build such infrastructure they must avail the WTO’s Enhanced Integrated Framework for LDCs, the UN Technology Bank for LDCs and bilateral/multilateral Aid for Trade (AfT) programmes to reinforce trading capacities especially for digital trading. This will be particularly useful for unique new trading opportunities such as in the UK post-Brexit and China.

China and the Commonwealth: Linkages beyond COVID-19

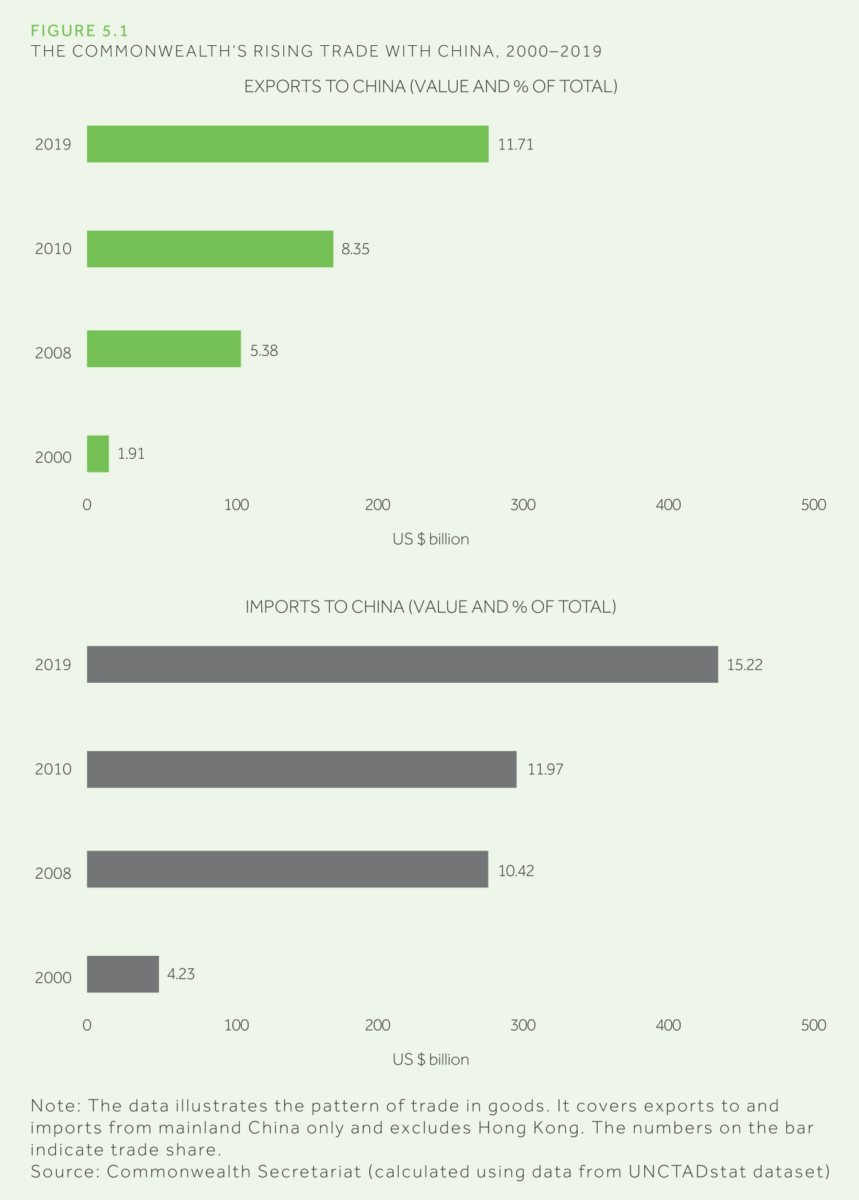

The trade relations between the Commonwealth states and China have been steadily deepening over the past few decades and have remained relatively insulated against the economic shocks caused by the pandemic. In 2019, China was the Commonwealth’s third-largest trading partner (the top two being the US and EU-28) constituting 12 per cent and 15 per cent of Commonwealth exports and imports respectively. The Commonwealth’s share of exports to China have multiplied by 6 from around 2 per cent in 1999 to 12 per cent in 2019 whilst imports from China have risen four-fold to 15 per cent over the same duration. Given their proximity to China, the Commonwealth states of South Asia and the Asia-Pacific regions have a higher reliance on China in terms of trade than other counterparts.

Figure 5.1: The Commonwealth’s Rising Trade with China, 2000-2019

Being the only country across the globe to register positive growth (2.3 per cent) in 2020, with its economy predicted to expand by a further 8.4 per cent in 2021. The spill-over resulting from this presents lucrative opportunities for Commonwealth states to reignite trade flows in the aftermath of the pandemic. Firstly, Commonwealth LDCs, in particular, may gain duty-free access for their exports. Secondly, China is a signatory of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership which includes 5 members of the Commonwealth; and having signed it three months earlier than expected, it is evident that Beijing deems the agreement vital. China also has separate Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Australia and New Zealand in the Pacific, Singapore, Brunei and Malaysia in Southeast Asia, Pakistan and the Maldives in South Asia, and Mauritius in Africa which should be prioritised and further advanced by these Commonwealth states. Africa as a region has been quite diligent in the upkeep of its trade relations with China; 2020 marked the 20th anniversary of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) under which the Beijing Action Plan 2019-2021 provides significant economic, industrial, and investment-related cooperation including the China-Africa Private Sector Forum and an imports (from Africa) financing fund of US$5 billion. Through the Belt and Road Initiative China also provides Africa financial support for the development of the continent’s physical infrastructure. Lastly, Commonwealth countries that are tourist-heavy may benefit from well off Chinese tourists, once international travel resumes, as these travellers comprise 21 per cent of all tourism spending across the globe.

Burgeoning trading opportunities post-Brexit

On 31 January 2020, the UK officially left the EU, entering a transitional period until December 2020 during which the existing rules on trade, travel and other business between the UK and the bloc remained in force. As of January 2021, trade relations between the UK and the EU-27 is now administered via the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) which is an FTA blanketing all merchandise but limited services, leaving prospects for regulatory regimes to deviate over time. Due to the Northern Ireland protocol to the Withdrawal Agreement under which the UK exited the EU, the market conditions in Northern Ireland may differ.

UK-Commonwealth Trading Relations

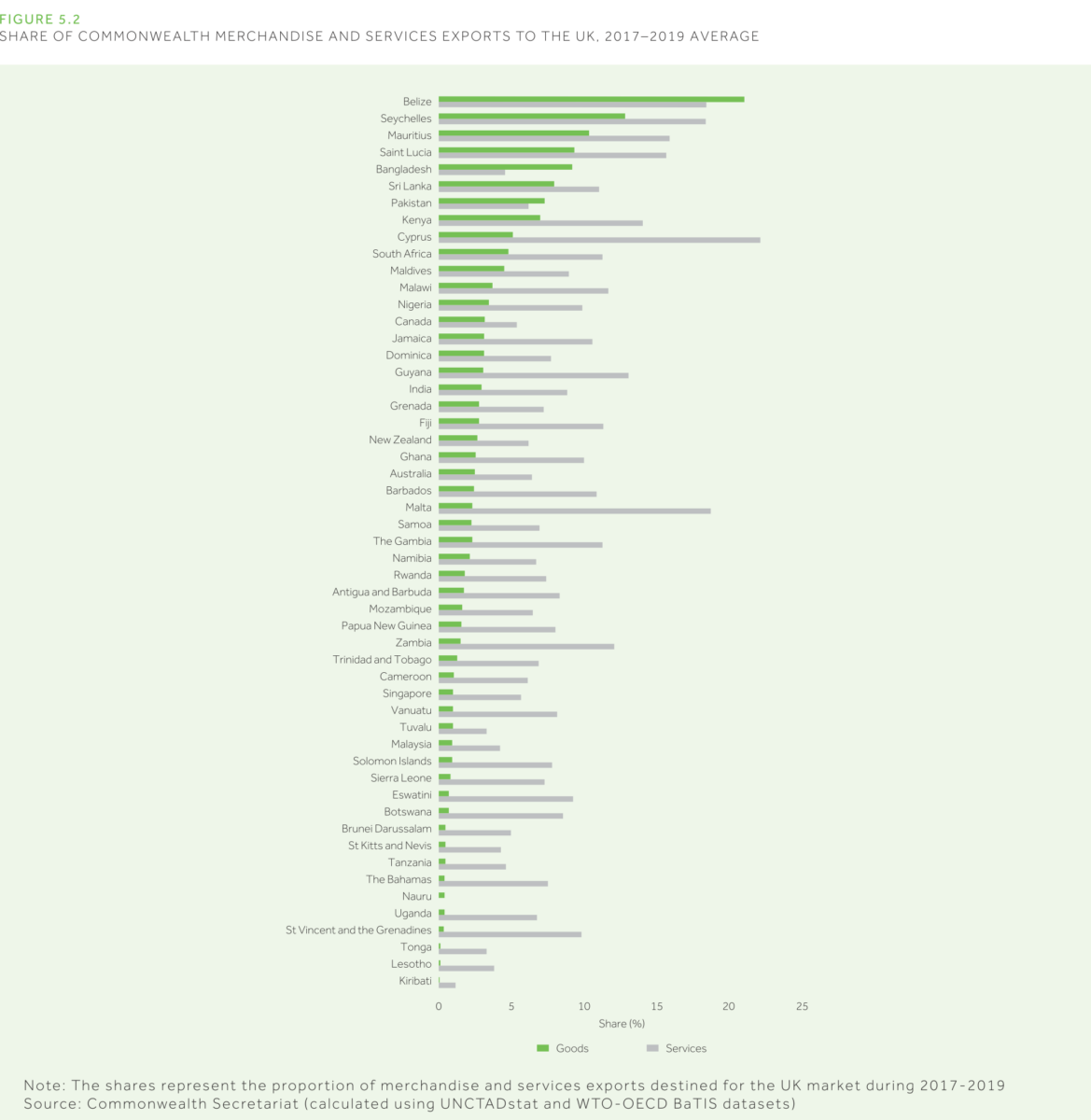

Commonwealth states’ exports to the UK in 2019 were estimated to be worth US$116 billion, meaning that the UK consumed 13 per cent of intra-Commonwealth goods exports and one-fourth of intra-bloc services exports [Figure 5.2]. This consumption is not uniform across the regions; Commonwealth Africa, Caribbean and Pacific (combined called ‘ACP’ states) are relatively more reliant on the UK’s exports, specifically for fish, sugar, rum, vegetables, beef, bananas, and textiles and apparel products. The 19 sub-Saharan African (SSA) states are the most reliant on the UK in terms of both goods and services exports with Belize shipping 20 per cent of its goods and 6 other member states trading more than 15 per cent of their total services with the UK. Small states seemingly dominate the services exports share, around 16 per cent overall, which mainly arise from the travel and tourism sectors. For LDC states the UK does not constitute a sizable share of their exports making up a 6 per cent share of the state category’s export, although for Bangladesh the share is higher, pegged at 9 per cent.

Figure 5.2: Share of Commonwealth Merchandise and Services Exports to the UK, 2017-2019 Average

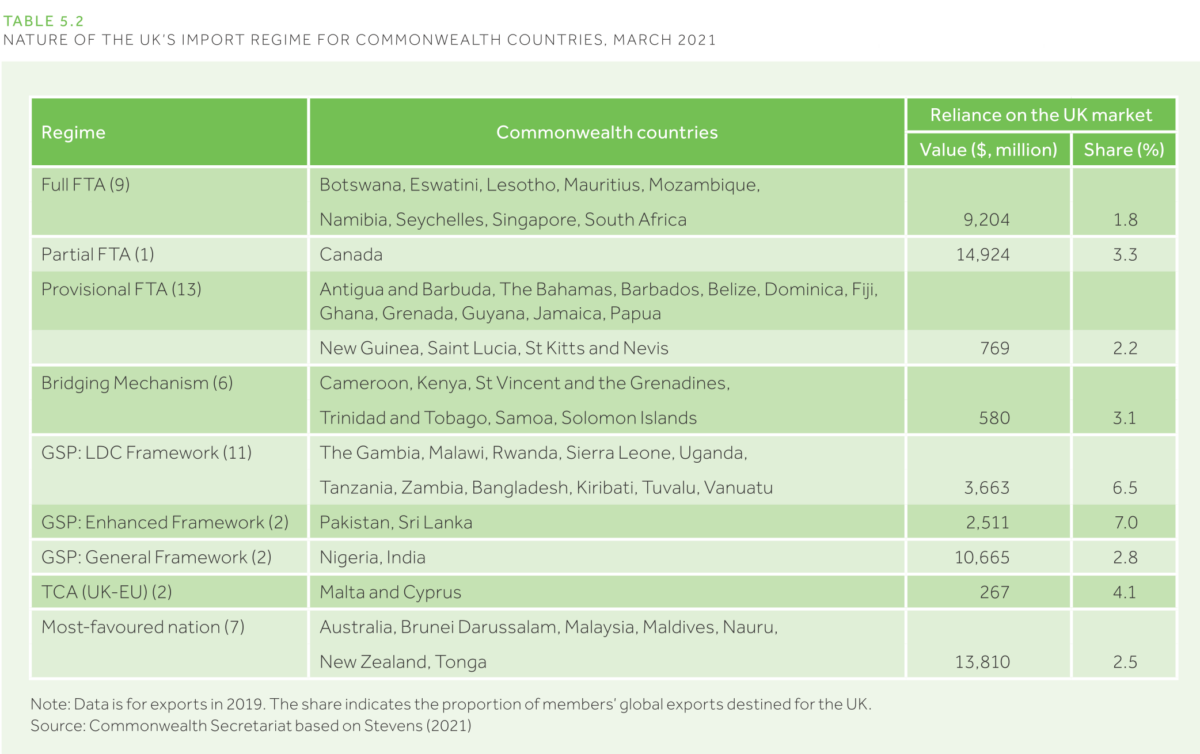

UK’s free trade regimes and Commonwealth imports

For Commonwealth states’ governing bodies and businesses, the UK-EU TCA offers clarity on the short-and-long-term effects on their trade with the country whilst also indicating potential new opportunities to ramp up their economic relationship with the UK [Table 5.2]. London’s trade regimes are modelled on those of the EU; meaning, the majority of the countries that have an FTA or economic partnership agreement (EPA) also have similar FTAs or Bridging Mechanism with the UK. For those that do not, they fall under the Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) which, similar to the EU version it is based on, contains three separate categories which offer broader market access compared to the WTO. The three segments include the LDC Framework GSP, offering market access congruent to the EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA), the Enhanced GSP Regime, similar to the EU’s GSP+ as well as the General Framework GSP for other low-and lower-middle-income countries. The UK GSP, excluding the LDC Framework, bars many goods, especially agricultural products, much like the EU Model. In addition, states considered overly competitive for specific products are “graduated” out of the GSP for those products e.g. India recently graduated out of the GSP for 2,652 different tariff lines.

Table 5.2: Nature of the UK’s Import Regime for Commonwealth countires, March 2021

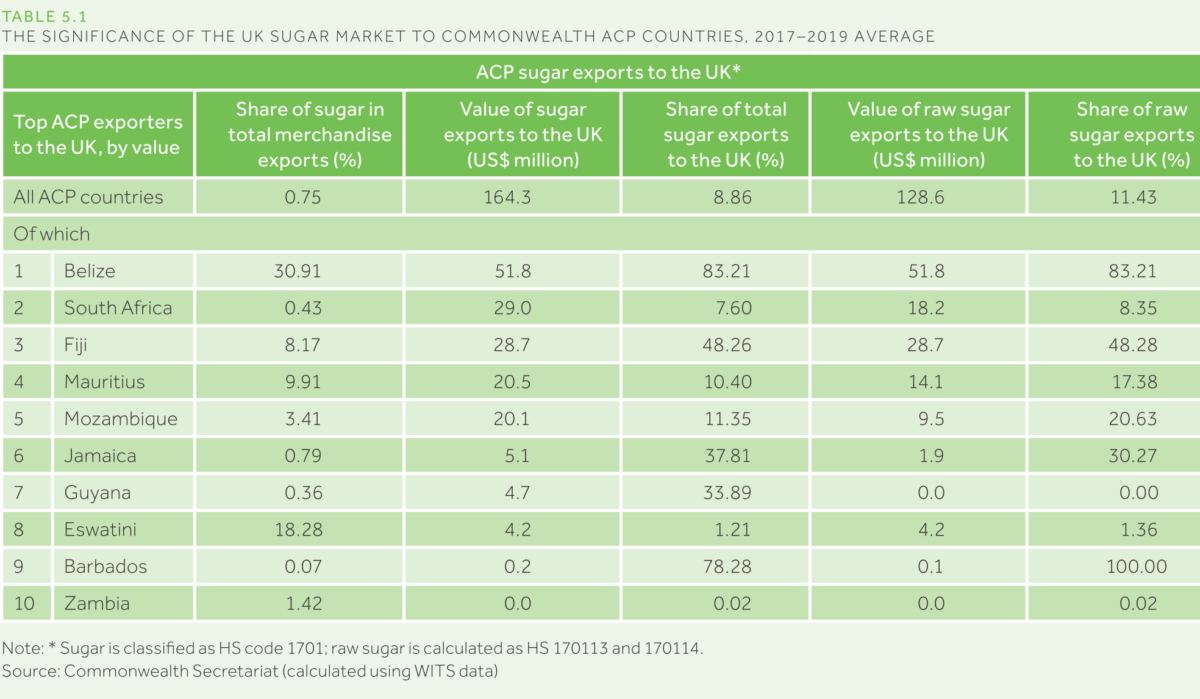

As for the ACP, the newly established trade agreements, implemented on 1 January 2021, with the UK continue to allow duty-free and quota-free (DFQF) export market access. These benefits notwithstanding, the UK’s endeavours for increasing future trade deals may heighten the competition for ACP suppliers which may subsequently jeopardize revenues for those ACP exporters reliant on the UK market for time-sensitive products such as bananas and sugar. Sugar is quite a significant export for many of these Commonwealth developing states [Table 5.1]; it constitutes 30 per cent of Belize’s total merchandise exports, 20 per cent of Eswatini’s, 10 per cent of Mauritius’ and 9 per cent for Fiji. This is especially the case for raw sugar; Barbados sends all raw sugar commodities to the UK, Belize around 83 per cent, and Fiji about 48 per cent. As previously mentioned, this is an exceedingly sensitive sector for these states as it attracts foreign exchange and creates a sizable share of jobs that sustains the livelihoods of many citizens. Back in 2017 when the UK was still a member of the EU, the bloc had reformed the high-priced sugar market to match world prices which had already diminished the value of the ACP’s sugar exports; and now with the implementation of an annual tariff-rate quota (ATQ) (on the same date as the DFQF) of 260,000 metric tonnes of raw sugar at zero tariffs, the competitive stakes for the ACP are even higher due to their comparatively higher production costs versus, for example, Brazil.

Table 5.1: The Significance of the UK Sugar Market to Commonwealth ACP Countries, 2017-2019 Average

Although both the UK and the EU provide DFQF access to ACP states, their bilateral TCA does not include diagonal cumulation amenities for the ACP, which could hamper the import of raw sugar from these states. Since more than 70 per cent of sugar consumption in the UK and EU, and sugar trade between the two parties, are typically processed food and drink, the lack of diagonal cumulation will not allow raw sugar imported from the ACP but refined locally to be considered to originate from the UK. And since these products will not benefit the UK via favoured rules of origin, the companies of the UK will opt to utilise EU or UK beet sugar instead. This is a significant challenge for the developing member states, especially in the maintenance of sustainable sugar agriculture that forms such a crucial share of their agro-industry and their efforts for recovering and building back better. Sugar cane constitutes 50 per cent of total value-added agricultural products for Eswatini and Mauritius, which goes to show that for ACP member states, decreasing exports will adversely affect their export earnings, create unemployment, and hamper progress towards SDG achievement, especially because this sector is the main source of revenue for smallholder producers that reside mainly in rural areas. Efforts must be put into seeking ways to preserve preferential market access to the UK and other Commonwealth countries with high intake of sugar imports to protect the economies of these ACP sugar-producing countries. Concurrently, the ACP countries must think of ways and policy frameworks to reduce costs and increase efficiency through bilateral and multilateral AfT initiatives.

The UK has improved upon policies of the EU regime but further reforms to simplify rules and lower restrictions are still required. A recurrent worry for many ACP exporters is the high standards and strict regulations for market access in the EU regime is superfluous if not borderline protectionist; for instance, South African citrus exports have been met with rigorous sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) conditions due to what is called ‘citrus black spot’ which is a harmless fungal disease. Fortunately, as of 1 April 2021, citrus exports into the UK no longer require these SPS certificates whilst other fruits and related products, such as guavas, kiwis, and passion fruit, are also exempted from these certificate requirements. This is because the UK’s less diverse range of climatic conditions and production, compared to that of the EU, incentivises the state to laxen health checks on a broad set of Commonwealth goods exports without risking the livelihoods of UK producers and consumers. Alluding back to Chapter 1 of this series, it was mentioned how, as of yet, Caribbean service providers have been unable to maximise the advantages of their EPA with the EU (the only one of its kind with ACP countries covering services) due to the barriers they face in the mutual recognition of standards and difficulties in acquiring visas. The UK is well-placed to assist its fellow member states in this regard, especially due to the large Caribbean diaspora that dwells within the country.

Despite reassuring measures placed for trade continuity for most Commonwealth states post-Brexit, multiple challenges remain. One such hurdle that Commonwealth countries face pertains to border disruptions obstructing supply chains transporting goods and services of Commonwealth origin across the EU-UK border. Additionally, agri-food exports from the Commonwealth’s developing member countries that are repackaged and/or processed within the triangular supply chain before being shipped onwards to their destination, will also be adversely affected by rules of origin conditions and face most-favoured-nation tariffs if the trade takes place outside of customs supervision. This is because such customs’ supervision under the Common Transit Convention procedures is quite cumbersome and difficult to activate along ACP supply chains due to inadequate infrastructure and staffing shortages. Another complication arises from border controls on transhipped goods becoming overly burdensome as the EU and UK standards continue to diverge. Agricultural products such as plant and animal exports will now have to be dually certified under both UK and EU standards. At the same time, no provisions have been set up to cross-recognise manufactured good standards which means all goods sold in both markets will have to be certified separately for each jurisdiction.

Outlook for the future of UK-Commonwealth Trade

The government of the UK has renewed its dedication to deepen economic ties with the Commonwealth during and beyond this post-pandemic recovery period and has made it a pillar of its “Global Britain” strategy. The UK hosted the UK-Africa Investment Summit in London 2020, appointed trade envoys for the Commonwealth Caribbean region, and is a leading contributor to, and advocate of the AfT, to help bolster Commonwealth developing states’ and LDCs’ regional and global trade. To provide a ‘springboard’ for the integration of the UK’s diplomacy and developmental efforts in the several new initiatives the government has proposed, the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office was set up in September 2020 as a separate department of the British government.

The UK is to complete bilateral FTAs that cover 80 per cent of its trade, including tariff-free trade with Commonwealth fellow states Australia, Canada, and New Zealand by 2022. Other FTAs with other Commonwealth states may also be a prospect for the future; for example, a UK-India FTA could increase the trade between the two states significantly. This would result in a greater increase of merchandise exports for the UK (an annual increase of 33 per cent) as compared to India (an annual increase of 12 per cent) perhaps due to the higher value of Indian tariffs. The UK also plans to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) this year that aside from the three previously mentioned Commonwealth members also includes Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, and Singapore.

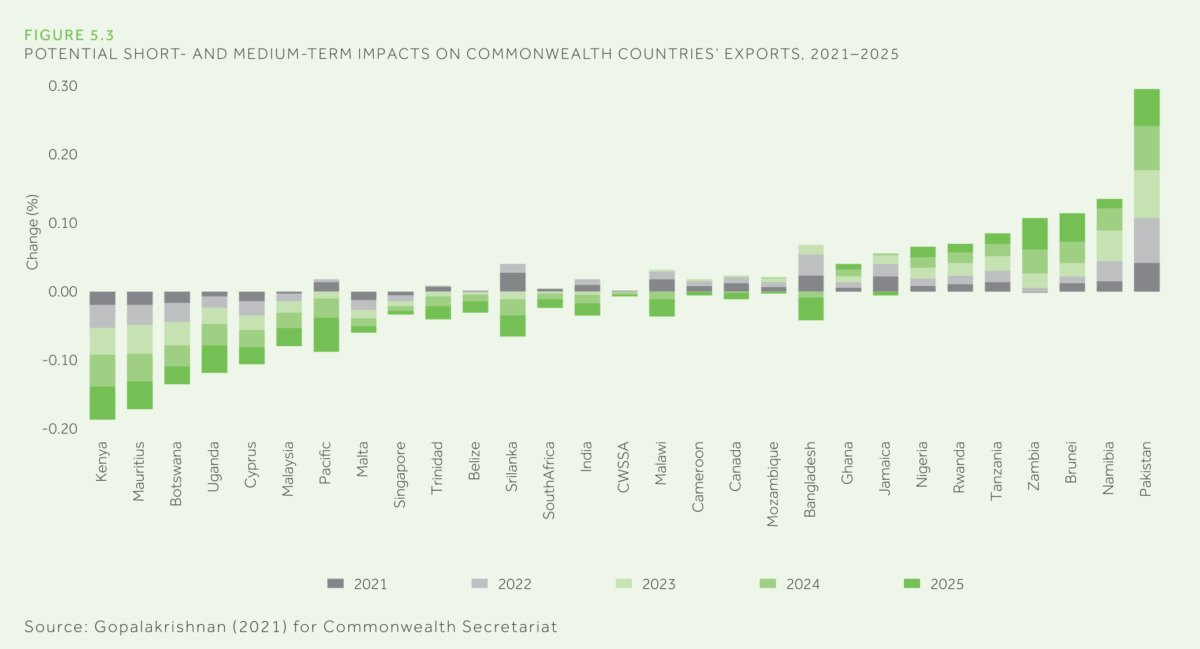

While these two new trade initiatives will cause a dynamic change for the trade between the UK and Commonwealth countries, adjustment support is crucial to ensure that it does not inflict more harm than good. [Figure 5.3] To elaborate, the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), a global research network, surmises that tariff-free trade between the UK and Australia, Canada, the EU-27, Japan, New Zealand, and the US may reduce trade flows for countries that are not part of these FTAs due to loss of preferences, especially Commonwealth LDCs. The exports of meat, textiles, leather, plastics and vehicles etc. will increasingly be sourced from these new FTA partners and Commonwealth countries that rely on the UK for their exports in specific commodities (e.g. apparel for Bangladesh, beef for Botswana, sugar for Belize, and tea and vegetables for Kenya) may experience a dip in their export, GDP, output, employment, and investment though fortunately these effects are expected to be small in scale and will wane over time. For some Commonwealth states that have the most competitive rates for their exports, such as Brunei Darussalam, Malta, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zambia, there will be marginal benefits arising from these new FTAs due to the reduction of input costs for the Commonwealth members as a result. These effects will also be gradual, over 5 years. To ensure minimal adverse effects to the Commonwealth member states, the UK can make concerted efforts to diversify and steer its food trade preferences towards the Commonwealth. At present, the UK imports US$65 billion worth of food per year, 70 per cent of which is sourced from the EU but proposed FTAs with Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, facilitated by the Commonwealth Standards Network, could effectively increase the share for Commonwealth states.

Figure 5.3: Potential Short – and – Medium Term Impacts on Commonwealth’ Countries Exports, 2021-2025

In 2018, two-thirds of services exports and half of the services imports of the UK were digitally delivered, and in 2019 the digital sector made up 7.6 per cent of the UK economy. As these digitised trade flows increase, so will lucrative prospects for digital trade with fellow Commonwealth states such as the UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement already being negotiated. Additionally, there are favourable openings for further collaboration in services which coupled with greater digitisation of economies provides new prospects for bilateral services trade in areas like financial services technology, especially in the context of increasing servicification of the Commonwealth economy. The UK could also contemplate giving LDCs commercial preference according to the WTO LDC waiver. Aside from LDCs, the UK is a key destination for services exports of the tourism reliant ACP countries as British tourists have been recorded to spend 7 times more than any other tourist that arrives in the Caribbean. UK arrivals are the top source of revenue for Barbados; the second largest source for Saint Lucia; and the third largest for St Kitts and Nevis. If they have not already, these ACP states must take full advantage of the repressed demands for international travel and excess savings collected during the pandemic by prioritising revamped branding and marketing of their tourism, entertainment, and hospitality services among more.

Reviving the Commonwealth tourism and travel sector

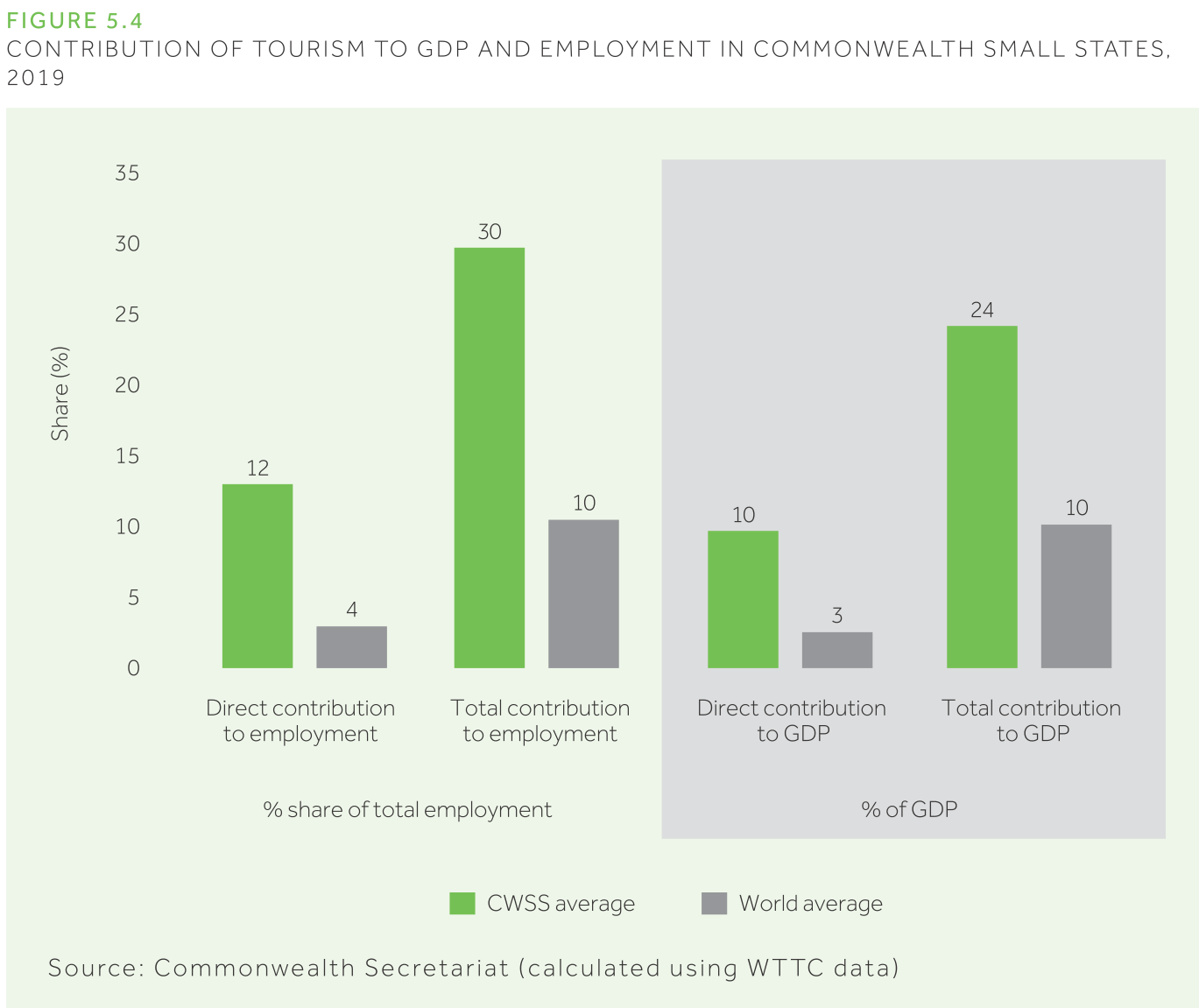

Globally, the tourism and travel sector has been the most severely affected and due to the small states’, especially SIDS’, heavy dependence on this sector for their economic well-being, these Commonwealth states have been the hardest hit, particularly the women, youth, returning migrants, and the informal sector. 14 of the 32 Commonwealth small states draw more than 30 per cent of their GDP from tourism [Figure 5.4]; to give a few cases, Maldives derives approximately 56 per cent, Antigua and Barbuda The Bahamas derive around 43 per cent and Barbados and Vanuatu around 30 per cent. To tackle the dire consequences of the pandemic, many of these member states have executed recovery plans for the tourism sector using industry body guidelines in two broad ways; in the short term, stimulus and relief packages for citizens were dispatched for immediate crisis management; and in the medium-to-long term recovery, policy responses to bolster industry resilience are being implemented as well as the adoption of operations facilitating technologies. Notwithstanding the fact that such responses are always specific to the unique nature and context of individual countries, valuable lessons can be learnt from their experiences, successes, and failures.

Figure 5.4: Contribution of Tourism to GDP and Employment in Commonwealth Small States, 2019

Maldives’ experience with reopening their borders for tourism presents an exemplary case of success. When the country cordoned off their borders in March 2020, the devastating impact on the economy was felt almost instantly due to which the Maldivian government blueprinted a sequenced plan for the reopening of the tourism sector by capitalising on its scattered islands several of which are solely inhabited by resort staff providing great ease in separating the tourist population from the civilian residences. Registering a positive result from this policy response, Maldives reopened its borders to the international community in July 2020 with access only allowed for visitors going to resorts, hotels, and/or liveaboard boats located on the segregated islands. In mid-October 2020, those tourism service providers and guesthouses meeting the required health standards were allowed to reopen their businesses with special permits allotted to those situated on islands inhabited by the local citizens to facilitate passengers for domestic transfers. To safeguard public health and maintain Standard Operating procedures (SOPs), international travellers are required to show a negative PCR test result for COVID-19 taken within 96 hours of their departure to Maldives and they must also complete an e-health declaration form 24 hours into their departure. Upon arrival, they must undergo thermal screening and those that do not have any symptoms are exempted from quarantine and are ready to start their holiday “mask-less” with no movement restrictions on the island. Some private resorts offer PCR tests for their guests upon their arrival, directing them to remain in their designated lodging until the results of the tests are available. The government then requires travellers to use an app called TraceEkee to jot down their movement to facilitate a community-driven system of contract tracing. The government has also ensured the protection of its tourism sector staff by launching a vaccination initiative for them. Such thorough safety measures have ensured tourist confidence in the Maldivian public health measures greatly helping in attracting more international travellers to come to Maldives.

To reinvigorate internal demand, governments across the globe have pushed for domestic staycations and intra-regional tourism to compensate for the lack of international consumption. Countries with a below-average number of cases have created “bubbles” i.e. travel corridors and offered long-term online work and residency conditions to “digital nomads” all whilst conducting digital marketing on a global scale. In addition to this, they have slowly began releasing more comprehensive health and safety protocols for international travel to lessen border restrictions which have effectively brought about more tourist trust in such tourism destination markets.

On the supply side of the tourism sector, some Commonwealth states have given precedence to maintaining their existing supply capacity along tourism value chains by investing in the revampment of crucial infrastructure, expanding production and service capacity, and workforce skill upgradation. Improved inter-sectoral, national, and regional cooperation on supply-side policy-making has enhanced supply-side readiness in all regions as well as the private sector. Unexpectedly, the pandemic has presented an opportunity for the amalgamation of conservation, ecology, creative industries and cultural heritage; for example, chimpanzee rehabilitation in The Gambia and the Liwonde National Park in Malawi. For the promotion of sustainable investment in their respective tourism sectors, Commonwealth developing countries can utilise AfT initiatives as well.

The digitalisation of the world’s economies has positively impacted the tourism sector. The use of technology for the promotion of virtual tourism and tourism expos and the use of e-commerce platforms can aid states in bettering their market strategies whilst creating avenues for local tourism suppliers to provide services to national as well as international customers. The usage of comparatively more high tech robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) can aid travel and accommodation booking and security measures in heavy presence areas such as airports and border crossings. These measures will improve safety and be a crucial line of defence in the face of future global crises. Augmented reality is a fascinating new area to explore and invest in to make it possible for individuals to virtually visit distant areas at a more affordable price than traditional travel. Such innovative technology is also being employed for the issuance of vaccine passports however this particular idea has faced opposition; concerns have been raised over the risk of this type of “passport” being discriminatory and political divisive because those unable (due to digital infrastructure gaps) or unwilling to access COVID-19 vaccines may have to deal with additional barriers on their movement and employment-seeking.

Capitalising digital infrastructure for trade development and competitiveness

As discussed previously in Chapters 2 and 4, the digitisation of trade has been an effective tool for attenuating the adverse impact of COVID and also for accelerating post-pandemic recovery. With digital trade becoming an increasingly important element of consideration for international trade and future investments, the enhanced competitiveness in economic performance may burden countries that struggle with gaps in digital infrastructure, such as LDCs and small states, hence the highest priority must be to guarantee their greater access and ability to afford the proper structure for ICT usage. To give an idea of the vast potential of the digital economy, the upgradation of internet services in Africa could contribute an extra US$180 billion to the region’s GDP by 2025 whilst enhancing supply chains and various sectors’ productivity, including their health care, agriculture, education, and financial services sectors. To harness this potential, however, member states must extend cellular internet services and integrate digital innovations across the entire population, not just large urban cities, to empower informal workers and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), particularly women and young entrepreneurs.

Rwanda’s digitally-led development

Rwanda provides an exemplary case for how digitalisation can aid an LDC country in overcoming obstacles in trade, caused by its geographically landlocked disposition, and emerge as a frontrunner in digital development within the African region. Since 2000, Rwanda has conducted back-to-back five-year plans targeting different means of digital development. The government began building the foundation of the ICT sector by drafting a set of enabling legal and regulatory frameworks and liberalising the telecommunications market. They then focused on constructing robust ICT infrastructure, including a country-wide fibre optic and cross-border terrestrial links to undersea cables through Kenya and Tanzania which has greatly enhanced internet capacity. Rwanda has always dedicated resources to honing the ICT sector employees’ digital skills through innovative partnerships and collaborative initiatives between the public and private sectors, with special emphasis on providing training in coding, software development and programming to the youth and working-age Rwandan women. The government has also incorporated basic digital skills training into the national curricula in primary and secondary schools. The government itself has adopted innovative technologies for its use and functions, consistently updating e-government services such as the one-stop online government portal IremboGov that can be paid for via mobile payment. Since 2017, the number of payments for e-government services has risen from 1 million to 8 million in 2020 showcasing the popularity of the convenient payment system.

Rwanda’s consistent efforts in delivering high-quality digital services delivery and accessibility have resulted in a ten-fold increase in international bandwidth access since 2015, a solid 4G network that covers 95 per cent of the country which is much higher than the regional average. These improvements have also helped streamline trade procedures for the member state; since the introduction of the Rwanda Electronic Single Window (RSEW), the average customs clearance duration for imports has been reduced by 40 per cent whilst exports by 55 per cent, lowering both direct and indirect trade costs. During COVID-19 the RSEW has played a key role in enabling employees to work from home which has kept the state’s trade flowing relatively well. Another important digital facility is the Rwanda Trade Portal, an online platform providing comprehensive information on 128 import-export procedures, transit protocols, and 203 laws and regulations concerning intra-and-trans-border trade. Rwanda’s health care sector has been a notable benefactor of this digitalisation; the country is on the path to come the first country ever to have a digital-first universal primary care service as a collaborative project being developed between the government and Babylon Healthcare, an online health care provider, since the past ten years. Such initiatives include the use of high-tech, for example, Zipline, a private company, deploys drones to deliver essential medical supplies to the remotest areas of Rwanda lowering costs and the burden on local hospital capacity to refrigerate delicate medical supplies i.e. blood, tissue, heat-sensitive medication etc.

Short and long term means of harnessing technology for economic recovery

Depending on their respective degree of ICT adoption, countries may use both short-to-medium and long term digitisation measures to bolster their economic recovery. In the short-to-medium term, online services, especially e-commerce, remain an effective measure in alleviating the adverse effects of the pandemic although such online activity may decline as vaccine roll-outs and treatments are more widely accessible. In the long term, investing in worker’s skill upgradation and frontier technologies related to Industry 4.0 has the potential to completely transform Commonwealth economies, build resilience for future crises, and incorporate sustainability into global supply chains.

E-commerce

E-commerce is defined as a digital platform for online transactions of products and services. The pandemic saw widespread use of e-commerce facilities due to which the online shopping mode is on the path to reaching trillion-dollar sales by 2022 worldwide. Yet, e-commerce activity is concentrated in the more developed nations, most notably in the US, and is not as significant in some Commonwealth states due to their lack of readiness to engage in e-commerce (factors explained previously in Chapter 2). This provides motivation and incentive for these member states to bridge the digital divide by investing not only in international e-commerce platforms but also in domestic e-markets. Such cyber marketplaces can help lower entry barriers, reduce transaction costs, and link the informal and formal sectors across territories potentially generating new opportunities for MSMEs and women-owned businesses to enter new markets.

E-commerce marketplaces are especially useful for the business community of Commonwealth SIDS and landlocked small states because it is the only means for them to still reach their international customers, as well as new markets through intermediaries, without burning through capital reserves. Due to the opportunity to reach new markets, some studies have also hypothesized that e-commerce platforms may result in export diversification which may entail a role for e-commerce to play in accelerating productivity growth through galvanised business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-customer (B2C) connections. Subsequently, e-commerce activity may increase the demand for logistic supply chain services that will create jobs for information technology, postal and delivery services. Leveraging these advantages depends on states’ overcoming existing challenges including poor digital infrastructure, lack of appropriate digital skills’ training, and insecure payment, dispute resolution, customs and logistics platforms.

Financial technology and innovation

Financial Technology (FinTech) was rapidly developed following the global financial crisis of 2008. Notable aspects of FinTech on the advanced side include virtual currencies, digital wallets, blockchains, and tech startups that provided multiple and innovative financial services unlike those of traditional banking. Such breakthroughs notwithstanding, it can be maintained that mobile money and associated lending/insurance services have been the most impactful on the livelihood of developing and LDC states; this is due to the services’ financial inclusivity for women and rural communities unable to access mainstream physical banking institutions. Amidst the pandemic, the significance of these financial services was once more highlighted as these mobile money solutions enabled the cashless transactions that have been a necessity in the cross-border supply of services under social distancing rules and regulations. Moreover, these financial services are frequently mentioned in UN SDGs as a key catalyst of global financial inclusion. Relating to the Commonwealth, the bloc’s member countries, both developed and developing ones, are at the forefront as pioneers of FinTech innovation and development. The UK, Singapore, Australia and Canada rank 2nd, 3rd, 8th, and 9th respectively on the 2020 Global Fintech Index City Rankings. Two SSA countries- South Africa and Kenya- ranked 37th and 42nd on the same index due to the M-Pesa mobile money revolution; Nigeria was also a notable inclusion on the list, ranking 52nd.

With an increasingly digital outlook for the future in sight, Commonwealth countries must be dedicated to strengthening collaboration with the private sector, particularly young entrepreneurs and tech startups, to expedite the distribution of financial services across all demographics inclusive of agri-tech and trade finance to bolster economic recuperation. Commonwealth states may consider “regulatory sandbox” approaches, which is a framework wherein FinTech startups are permitted to conduct experiments in a controlled environment which is supervised by supervisory regulators, to create avant-garde financial services and products. The Commonwealth Secretariats FinTech Toolkit is an invaluable resource for leaders, senior officials, and their teams to gain comprehensive knowledge on FinTech to help build their capabilities; this resource may also be used to build a pan-Commonwealth platform to develop “innovation hubs”.

Frontier Technologies

Frontier Technology, also dubbed “Industry 4.0”, is a category of revolutionary technology that has been created through arduous research and development (R&D) but has not been made available to the public as of yet due to its unpredictable and disruptive nature. Artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things, blockchain technology, 5G, 3D printing, robotics, and nanotechnology are some known examples of frontier technology the market of which currently stands at an estimate of US$350 billion and is predicted to grow to US$3.2 trillion by 2025. Due to its innovative and high-tech nature, it has massive potential to solve global problems, help bolster post-pandemic economic recovery, and achieve UN SDG goals. However, this advanced technology comes with equally severe risks e.g. geoengineering may fight climate change but may also invoke dire stratospheric changes, faster internet speeds may lead to as much misinformation as information etc. In the case of Commonwealth developing states and LDCs, the biggest risk these frontier technologies may bring about is an insurmountable widening of the digital divide between these states and their developed counterparts across the globe.

Such technological developments may affect job opportunities in the Commonwealth states in three ways. Firstly, frontier technology may both increase and decrease labour demand; more high-skilled labour forces will be needed to develop and supervise these mechanisms but the automation of certain tasks, mostly those that require lower skill levels, may result in income/job loss. Secondly, there is a positive correlation between frontier technology and labour productivity, meaning jobs that involve the use of digitisation generate higher productivity and also have the option of being carried out remotely which has been proven to be quite advantageous during the pandemic. Lastly, if the developing and LDC member states are given the proper support to catch up technologically to their developed peers, studies show that successful efforts will significantly reduce trade costs and subsequently increase their trade growth by 2.5 percentage points per annum by 2030. However, for LDCs that wish to continue traditional trading and focus on developing low-costing manufactured exports, the consequences of such purposefully constrained digital growth are not yet fully known.

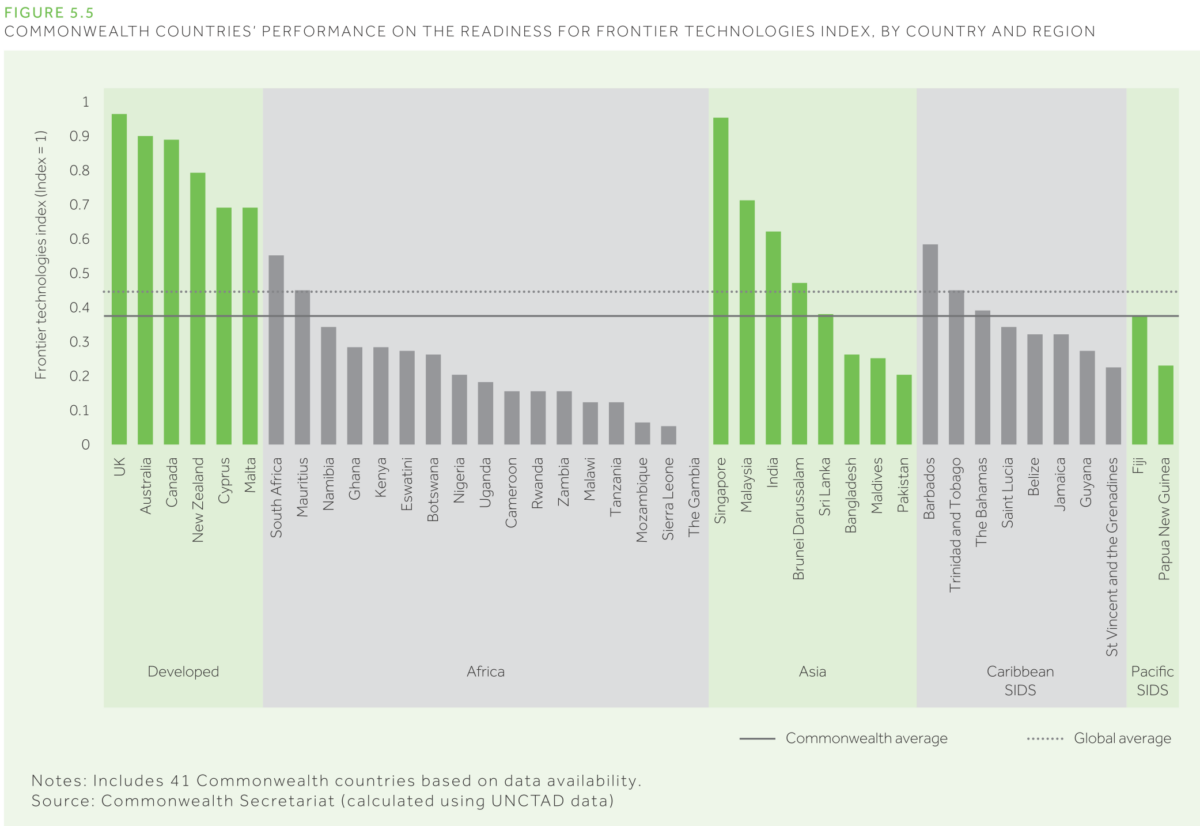

Although numerous Commonwealth countries have made commendable headway in mobilising frontier technology to elevate their economy including (but not limited to) their respective agriculture, energy, tourism and manufacturing sectors; the majority of the bloc’s members have below-world average scores in the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Readiness for Frontier Technologies Index 2019 [Figure 5.5]. Singapore and the UK, with their respective scores of 0.96 and 0.95, are the highest-scoring member states of the Commonwealth, being amongst the top 5 globally on the Index along with the US (1.00), Switzerland (0.97), and Sweden (0.96). Region-wise, Commonwealth Asia had the highest average score due to the above global average performance of Singapore, Malaysia, India, and Brunei Darussalam; India in particular outperformed relative to its GDP mainly because of its surplus of skilled human resources and high-level R&D capabilities. Aside from Commonwealth Asia, Commonwealth Caribbean SIDS scored higher than Commonwealth Africa with Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, and The Bahamas scoring above both the global and Commonwealth average. Two SSA countries, South Africa and Mauritius, also grossed above-average scores due to their well-developed ICT sectors. The Index echoes this trade Review’s previously mentioned concern of the LDCs being left behind amidst this technological revolution and underscores the urgent need to support these states by developing inclusive policy frameworks to bridge these infrastructural gaps. For developing countries, the main priority should be unimpeded structural economic transformation and sharper alignment between technological and industrial policies.

Figure 5.5: Commonwealth Countries: Performance On The Readiness for Frontier Technologies Index, by Country and Region

Developing effective frameworks for digital trade governance

Internet and data are the lifeblood of the digital economy; stored, processed, and transferred across and beyond national borders. The regulation of this digital ecosystem requires strict due diligence in governance policies regarding data protection and privacy, cyber security, consumer protection, data processing and localisation, and digital signatures. All Commonwealth developed countries have successfully applied fitting frameworks however the majority of the developing countries, in particular the SSA countries and small states, have yet to successfully establish the required legislative regulations. Favourably, progress in developing, collaborating and harmonising standardised rules for digital trade via bilateral and regional trade deals or initiatives at the WTO has been fruitful; between 2010 and 2018, approximately 60 per cent of all regional trade agreements have incorporated provisions for digital trade. One notable agreement under negotiation is the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)’s scheduled protocol on e-commerce, an opportunity for Commonwealth Africa to develop unified rules and regulations. All Commonwealth states are encouraged to establish such kinds of digital free trade agreements. It is advised for them to model future agreements after the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile and the two Commonwealth member states- New Zealand and Singapore.

DEPA: The trade model for the digital future?

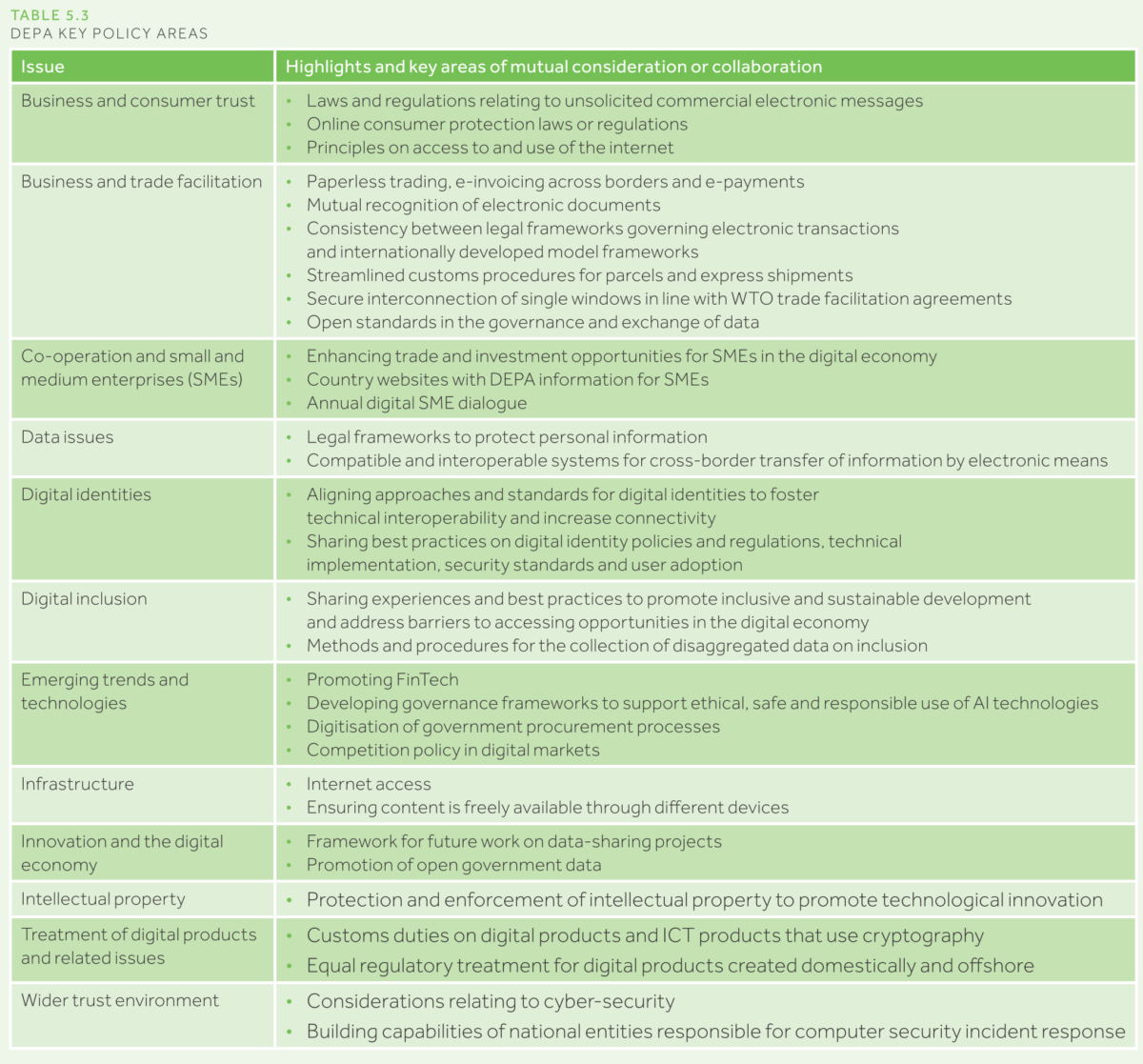

The DEPA was enforced on 7 January 2021, seeking to address the digital trade barriers between these three states with an open invitation for other like-minded countries to join. It underscores the significance of digital technologies for the development of economic growth via innovative production, improved productivity and better market access [Table 5.3]. The Agreement aims to provide involved parties with a forum to brainstorm solutions for common digital-trade related issues and navigate interoperability amongst their respective digital systems to create an interconnected digital economy. Although the Agreement puts heavy emphasis on cooperation, it acknowledges the pertinence of states’ internal policies and regulations, allowing flexibility for them to adjust the Agreement’s rules accordingly. The DEPA will gradually transform over time as new technological advancements, and their consequent new challenges, materialise; and as more Commonwealth states begin to integrate into the motherboard of the international digital economy, the Agreement’s scope will expand and be further refined to accommodate more complex deals and regulations. Recently, Canada has shown interest in becoming a member of the DEPA after launching several public consultations regarding its terms and conditions. As of yet, the DEPA is the most ambitious digital agreement in force and presents itself as a useful template for Commonwealth member states seeking to facilitate their economies’ digitalisation and digital trade across the globe.

Table 5.3: Depa Key Policy Areas

Multilateralism and digital trade frameworks

Relatively, multilateral rule-making has been slower in terms of progression; the WTO Work Programme on E-Commerce (established in 1988) permits conversation on e-commerce related trade issues regarding the moratorium on customs duties levied on electronic transmissions. Back in January 2017, 71 WTO members had drafted a Joint Statement Initiative on trade-related features of e-commerce and launched negotiations encouraging all WTO members to partake. 3 years since, with an addition of 16 more WTO members, 86 member states have drafted a negotiating text regarding five major issues on which they endeavour to reach a multilateral consensus on by the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference (MC12): e-commerce openness, trust, telecommunications and market access, and miscellaneous cross-cutting issues. Meanwhile, other members of the WTO continue to work on developing the existing WTO Work Programme to enhance domestic digital trade capacity and overcome digital divides.

The inevitable progression of the digital economy post-COVID will bring about a range of cross-border issues in digital trade, services, competition and taxations i.e. customs duties on e-commerce and digital services; this will demand better regional and global unanimity on the rules and regulations for goods and services. As the policy landscape for digital services continues to evolve, the WTO and trade agreements across the globe must change their perception of, and negotiation mechanisms for, the future of trading goods and services. To elaborate, in Chapter 1 it was discussed how the delivery of services was shifted to Mode 1 due to social distancing measures; however, digitalisation facilitates physical services such as road transport, construction, engineering, retail and even tourism to an extent (for now), whether domestic or across borders, through digital means. In light of this, governments and policymakers may devise ways to cooperate and coordinate on reducing regulatory fragmentation; for example, regionalised e-payment systems alongside integrated rules on data and privacy may contribute to cross-border trade via e-commerce platforms.

Developing a reinvigorated Aid for Digital Trade Initiative

The Commonwealth developed states, namely Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK, have been at the forefront in advocating for and donating to, the WTO’s Aid for Trade (AfT) initiative which was set up in 2005 to assist developing states increase production and supply-side capacity. Over these past 15 years, the AfT has been a significant voice for addressing the constraints felt by developing members of the WTO that prevent them from participating and benefitting from international trade. Initially, AfT initiatives were limited to setting up network communications infrastructure and digitalising import-export procedures; by 2017, issues of connectivity, e-commerce and readiness to engage within the global digital economy became the forefront agendas for the AfT resulting in the increased promotion of online connectivity and digital inclusiveness campaigns. Simultaneously, WTO member countries began negotiations on e-commerce prior to the WTO’s 11th Ministerial Conference (MC11) to focus more digital trade in bilateral, regional and mega-regional FTAs.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Credit Reporting System, the AfT funding towards digitisation has been positively impactful for the ICT sectors, with Commonwealth Africa and Asia states receiving US$36 million and US$40 million, respectively, largely from the contributions to the AfT by International Development Association donors and Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members. Despite such positive contributions, the available data on AfT capital flows for promoting digital trade is not specific and comprehensive enough to showcase which specific areas of digitisation have been contributed to; hence, more data must be extracted to accurately analyse the AfT’s input in firms’ and states’ different digital trade facilities. Regardless of the current ambiguity of donation specifics, it is clear that AfT contributions can greatly improve countries’ digital trade equipment in a short span of time which may be maximised through efficient allotment of resources and capital.

A study was conducted for the Commonwealth Secretariat on the Aid for Digital Trade agenda wherein four specific areas of focus are highlighted:

1) Infrastructure

Similar to the cases of other infrastructure development projects funded by the AfT, Aid for Digital Trade programmes will be useful for intervening in digital infrastructure construction projects that require redirecting focus to capacity-building and technical assistance.

2) Digital skills adoption

To ensure an inclusive digital economy, individuals, consumers, entrepreneurs and businesses involved in digital trade must be empowered and their access to digital technologies must be facilitated. Commonwealth governance bodies are implored to develop supportive policy and regulatory environments that maximise the benefits of the digital economy for their citizens.

3) E-government

Aid for Digital Trade can help lessen the burden of costs incurred by the development and implementation of e-government systems and services that will improve the ease of doing business for Commonwealth states.

4) Financial inclusion

Financial services are increasingly digitising their platforms, especially for e-commerce, FinTech and other financial services such as mobile banking. The Aid for Digital Trade can be very effective in making such digital innovations more mainstream and providing better access to these services for broader demographics.

Evidently, the Aid for Digital Trade initiatives could be crucial for Commonwealth states looking to capitalise on the unprecedented benefits of digital trade provided this aid is in addition to pre-existing official and governmental aid and other AfT cash flows. This is to guarantee that Aid for Digital Trade resources are not simply redirections of cash flows meant for non-digital trade development projects.

Striving for paperless trade

Currently, international trade remains heavily paper-based; an estimated four billion documents are circulated in the system which results in inefficient handling time and additional costs for all exporters, particularly for Commonwealth developing MSMEs. Case in point, it is reported that a singular shipment of roses from Kenya to Rotterdam produces a 25 cm high pile of documents. Whilst automation of the documentation could cut down documentation time, it does not solve the problems caused by outdated laws and the absence of efficient best practices.

The gradual post-recovery period highlights an important lesson to be learnt about the virtues of digitised customs and border procedures going paperless for environmental sustainability as well as protection of customs personnel due to minimal physical proximity requirements in the absence of physical documentation. Previously, a study showcased that a 10 per cent decrease in the overall price for a commodity/product to exit a Commonwealth country resulted in a 7.4 per cent increase in their global exports whereas for the global average it would increase by 6.8 per cent, almost a whole per cent lower. In terms of intra-Commonwealth trade, it would increase exports by 5 per cent on average.

As mentioned before in Chapter 4, 48 of the 50 Commonwealth countries that are members of the WTO ratified the TFA under which Article 10.4 requires members to set up a national single window using ICT means to the most “extent practicable” using the TFA Facility and other such avenues. The Commonwealth developing countries inclusive of some LDCs have already set up such facilities; however, improvements can be made through the use of paperless trade solutions using digitalisation, especially via frontier technology such as blockchains and eventually the “Rules as Code” which is the concept of translating standard trade regulations into business-friendly language that can be read by humans and machines alike. Amidst COVID-19, many governments adopted a variety of digital trade measures to accelerate cross-border clearance procedures for goods i.e. electronic processing of trade-related documents (on-site as well as in advance), electronic payment of taxes and levied duties, digital certificates and signatures, automated processing of trade declarations, and electronic pre-arrival processing. If such temporary digitalised measures are made permanent, it would make vast and meaningful changes in the post-COVID trading system.

According to the 2019 UN Trade Facilitation Survey, many Commonwealth countries are making significant headway in paperless trade implementation; the Commonwealth developed states and Asian states have converted 77 per cent and 68.5 per cent, respectively, of their trade into a paperless form which is above the global average of 61 per cent (as of 2021 it is 65 per cent) whilst the 9 African states- Botswana, Cameroon, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia- are nearing the global average at 57.2 per cent. Cross-border paperless trade is far more challenging, with the global average being at 36 per cent although it presents a wide scope for countries to start focusing on enlarging capacity, updating ICT systems and digitalising supply chains. During the peak of COVID-19 in 2020, the percentage of paperless trade has most likely increased. Regionally, Commonwealth Pacific countries have the highest potential for transforming their trade facilitation with the help of technology; to give an example, Australia and Vanuatu recently partnered up to automate Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) certificates cutting the processing time of applications down to just 10 minutes.

Further advancement of cross-border paperless trade measures, including definitive legal frameworks for electronic transactions (for instance in e-commerce) and electronic SPS certificates to bolster agricultural trade amongst countries, are being discussed for a supposed TFA-Plus scheme. This may prove vital to bridge the gap in international cooperation on integrated legal and institutional frameworks especially for Commonwealth states who need it for successful cross-border paperless trade expansion. To present a case, the Framework Agreement on Facilitation of Cross-Border Paperless Trade in Asia and the Pacific was enforced in February of 2021. The participants include digital powerhouses Singapore, Malaysia and India that scored 72 per cent, 56 per cent and 55.6 per cent respectively in cross-border paperless trade, again far higher than the global average. Singapore stands out the most mainly because it has incorporated the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records into its framework and is leading the implementation of TradeTrust, a blockchain-based maritime trade tool. Having recently ratified the Agreement, it is estimated that Bangladesh could potentially reduce trade costs by a whopping 33 per cent translating to annual savings worth US$700 million provided it implements the WTO TFA alongside its paperless trade.

Promoting sustainable trade and a more circular economy

The post-COVID era is an opportune chance for the Commonwealth to advance their UN SDG goals, especially SDG 12 titled ‘responsible consumption and production’ also counting trade policy and agreements, as well as to advance the principles of a circular economy whereby economies consume fewer resources, emit less carbon, and decrease waste to minimal levels. Betwixt these two goals, there is also a chance to build more buoyancy into these states’ supply chains and industries for a stronger recovery. Without efforts towards achieving these targets, not only would the recovery period be elongated, but further environmental harm and pollution will adversely affect societies and economies worldwide with a risk of such unsustainable models becoming irreversible.

Technological advancement is a crucial catalyst for the transition towards sustainable growth and development, ‘green job’ creation, renewable energy production and robustion of regional and local supply chains. Blockchains, for example, can be a useful tool to embed sustainable attributes into products by lowering CO2 footprints, plastic content and waste whilst also increasing compliance investment. During this push towards sustainable consumption through digitisation, countries must capitalise on technology to augment the agriculture and fishing sectors by raising yields during and after the pandemic. Some examples of how this may be carried out include enabling climate-smart advisory services to counter drought seasons and produce short season seed varieties, deploying precision farming to decrease the harmful effects of agrochemicals, and setting up index-based insurance services which could be critical in protecting farmers against damages caused by natural disasters. Such initiatives will improve sustainable economic growth in these sectors for Commonwealth countries, provided targeted interventions are carried out to guarantee farmers and stakeholders involved in the value chains are given the proper equipment to deal with the massive changes such digital farming solutions will bring about. Some Commonwealth countries have already successfully incorporated digital technologies in the use of maritime resources by encouraging higher levels of information sharing, data-driven subsidies and tariff policies whilst increasing the accuracy of fish tracking and regulation (in particular IUU fishing) via the use of satellites and drones. These actions have resulted in the maximisation of these countries’ current global fleet hence they present themselves as good role models for other member states to follow and seek guidance from.

Current Connectivity Agenda Initiatives in the Commonwealth

During the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) that took place in April 2018, the Leaders of the Commonwealth approved the Commonwealth Connectivity Agenda (CCA) setting up an objective to bolster Commonwealth trade and investment links and a goal to raise intra-bloc trade to US$2 trillion by 2030. The CCA will also involve the development of tools necessary for national policy-making facilitation and economic and industrial development, the most notable of which is a policymaker’s guide to Manufacturing 4.0. This tool is quite practical and will assist its readers in understanding both the benefits as well as implications of Manufacturing 4.0 on economies. Particularly for tackling gaps in digital skills across the Commonwealth, the CCA is creating a series of Youth Digital Skills Strategies to upgrade member states’ institutional capacity for youth digital skills training.

The Agenda is dissected into five separate clusters, each of which is chaired by a Commonwealth state voluntarily. Of these clusters, the Digital Connectivity Cluster is in charge of issues pertaining to the digital economy; future sessions will focus on and specialise in digitising trade facilitation and ICT infrastructure policy development with the aim to maximise digital innovation and inclusivity wherever possible. The Physical Connectivity Cluster is involved in addressing issues related to accessibility and equal distribution of both hard and soft infrastructure that is needed for economic development. Within the Cluster, members have eagerly compared notes on experience with addressing infrastructural needs and collectively ratified the Agreed Principles on Sustainable Investment in digital infrastructure, identifying six areas in need of prompt actions. In 2020, the Cluster members, partnering with the World Bank and the Commonwealth Secretariat, conducted training on the Infrastructure Prioritisation Framework, and as the CCA progresses into the implementation phase post-2021 CHOGM, the initiative will be extended to include virtual training modules along with other technical teaching areas related to digital infrastructure.

The Supply Side Cluster provides base support to create a foundational link between sectors. This is important because whilst digitisation is a known game-changer for enhancing smallholder agriculture operations and fisheries, there is a dearth of understanding of the concept amongst traditional workers of these sectors. Therefore the Supply Side Cluster is instrumental in guiding these stakeholders in their uptake of digitalisation, via programs such as the Business Development Service Capacity Building activity for Agricultural, Fisheries, and Digital MSMEs.

The initiatives explained above are proof of the Commonwealth’s commitment to advancing knowledge-sharing and capacity building amongst member states to equip them not only for a post-pandemic economic recovery but also an inevitably digital future.