The Decentralised Commonwealth Dominance

The Commonwealth’s Regional and Multilateral Trade Response to COVID-19

Trade Multilateralism and the Commonwealth

Undoubtedly, trade is an essential element of sustainable economic development which has alleviated millions of individuals out of poverty worldwide. The importance of global trade to universal prosperity is showcased in the WTO’s membership which, over the 25 years since its establishment in the 1994 Marrakesh Agreement, has increased to 164 members, including 50 Commonwealth states, collectively constituting 96 per cent of global GDP. The WTO has continued the mission of its antecedent, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), as a platform for global collaboration towards lowering global tariffs, supporting economies during crises and providing a binding system of rules and codes of conduct to ensure uniformity, equality, and predictability of global trade. Its success in trade facilitation is evident in its contributions towards the almost threefold increase in global trade volume since its inception in 1995.

Besides being a forum for global cooperation, the WTO has implemented several agreements as an extension of its global endeavour for multilateral trade growth. The most notable is the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) which was ratified in February of 2017 under the Doha Round of Trade Negotiations; its innovative framework for capacity-building via expedition of goods’ clearance and transboundary movement has enhanced the efficiency of developing states’ border procedures and merchandise flows and which can increase global trade value by US$1 trillion annually. Similarly, the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is an international legal agreement between its member nations that has garnered a positive response during COVID-19 due to its provision of a legal framework (under WTO regulations) to allow developing countries greater access to cost-effective medical supplies. Another successful initiative by the WTO is the Aid for Trade initiative that was incepted during the 2005 WTO Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong, aiding developing countries in addressing issues related to lack of trade capacity. Besides trade facilitation, the WTO has a crucial role in international trade arbitration; to date, the WTO has settled 600 trade disputes. In terms of gender equality, the Trade Review highlights the fact that the new Director-General of the WTO, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweaka of Nigeria, is the first woman to be appointed to the role. For the first time in history, along with Dr Okonjo-Iweaka, the UNCTAD and the International Trade Centre (ITC) have also appointed women leads; Pamela Coke-Hamilton is the Executive Director of the ITC and Isabelle Durant is the current Acting Secretary-General of the UNCTAD. Of these three women, Dr Okonjo-Iweaka and Dr Coke-Hamilton both belong to Commonwealth member states.

While the WTO has made commendable progress, the future of trade multilateralism remains unclear. As the world struggles with the adverse impact of the pandemic and is in dire need of trade stability, the WTO members’ interests and views on the efficacy of multilateralism continue to diversify, mounting more challenges and pressure on the WTO to manage world trade and its recovery. These challenges have been worsened by the delay of the 2015 Doha Round trade talks (some members did not reaffirm the mandate as they believe new measures must be adopted for better outcomes) as well as the stalling of the Dispute Settlement Understanding mechanism due to the termination of the WTO’s Appellate Body in December of 2019. The consequent halt in the progress of multilateral rule-making is making states more inclined to sign bilateral and/or regional trade deals to further economic integration which, coupled with the changing structure (or in some cases, reversal) of complex global supply chains and shift towards near-shoring by governments and MNCs, will decrease future cross-border trade of intermediate components of finished goods over long distances thus negatively affecting trade multilateralism and having negative implications for Commonwealth states. In addition, as global trade continues to transition towards the digitalisation of goods and services, governments will increasingly rely on frontier technologies e.g. 3D printing, nanotechnology, robotics etc. to bypass the need to import intermediate goods from low-wage countries and manufacture products proximate to their respective points of goods’ consumption. This may likely result in the decline of the importance of traditional comparative advantages i.e. low costing high-skilled labour. Such shifts in the global trade system will consequently lower the dependency of countries on open trade rules, more so for merchandise than services perhaps, and promote more unilateral re-shoring policies. These developments combined with the effects of the pandemic pose a heavy burden on the WTO to rapidly adapt to the current volatile environment whilst improving its facilitation of data, technology and knowledge trade so that it may remain vital for WTO member states.

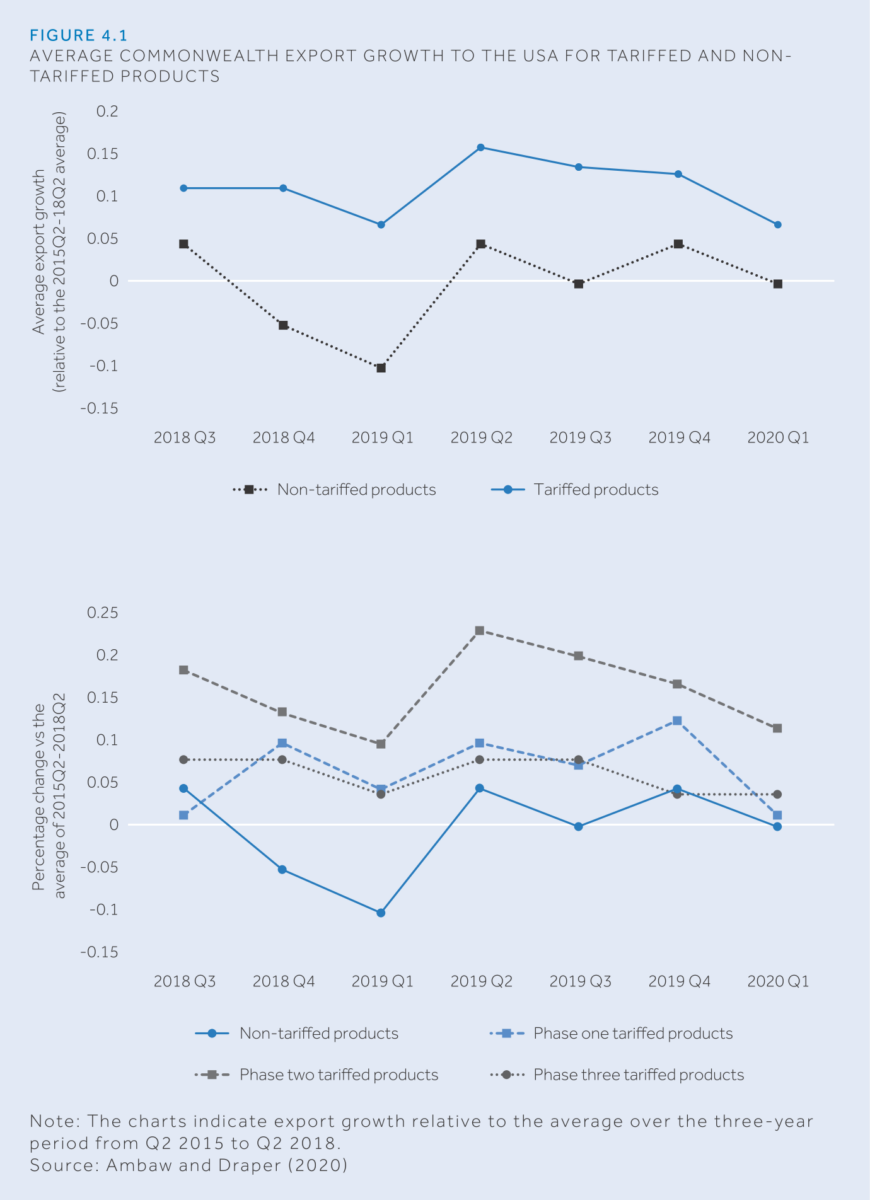

While these issues are already jeopardizing the future of multilateralism in trade, managing its global trade regulations amidst the US-China conflict remains the biggest challenge for the WTO. The geopolitical rivalry between the two leading states has notably hindered international trade and has had significant effects on Commonwealth countries’ exports. The Commonwealth Secretariat conducted a regression analysis study to analyse empirically the trade dispute’s impact on Commonwealth exports and supply chains. The resulting data found that before the conflict began, there was a positive correlation between US imports from China and Commonwealth countries; once the tariffs increased, Commonwealth exports, of both tariffed and non-tariffed merchandise, to the US plummeted except for a few Commonwealth Asian countries. Although, the dispute has hindered the Asian member states’ supply chains by lowering the growth rate of their exports of parts and components thereof, indicating just how deeply integrated within the GVCs these economies are. Simultaneously, Chinese imports into Commonwealth countries surged as China diverted imports meant for the US.

Figure 4.1: Average Commonwealth export growth to the USA for tariffed and non-tariffed products

The Commonwealth has been an active advocate of multilateralism since before the pandemic; in October 2019, Trade Ministers of the Commonwealth issued a collective Commonwealth Statement on the Multilateral Trading System. To counteract anti-multilateral sentiments, the Heads of Government of the Commonwealth have unanimously proclaimed their commitment to strengthen transparent, inclusive and fair free trade in an open rules-based and multilateral trading system that will prioritise the development of the LDCs and small states, under Paragraph 16 of the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting Communiqué, and highlighted the potential negative effects that protectionism may entail not only on vulnerable states but also the global economy. The multilateral trading system is of great importance to almost all Commonwealth states, especially LDCs, SSAs, and small states, as it provides them with a chance to be on equal footing with advanced economies in the international playing field of world trade. Furthermore, multilateralism creates a forum for Commonwealth developed and developing states alike to further their developmental and economic interests, especially for battling against harmful pathogens and protectionism simultaneously during this global crisis of COVID-19.

Trade Multilateralism during COVID-19

The global shift towards virtual and hybrid negotiations

As the pandemic intensified in March 2020, both international and national organisations across the world, including the WTO, transitioned their diplomatic discussions and negotiations to virtual and hybrid platforms which have created both challenges and innovative opportunities for participants. To better understand the experience of ambassadors and diplomats of Commonwealth developing states who attended virtual and hybrid WTO meetings, a study was conducted this year for the Commonwealth Secretariat, wherein these diplomats were interviewed and asked about what challenges they faced during their participation. Three main challenges were highlighted in the study; the first challenge, which was mainly felt by developing member states, were the technical difficulties in attending the online sessions. Weak internet connections were especially cumbersome due to the dearth of knowledge and skills to solve the connectivity problems. Besides the disruptive internet issues, there was concern that there were not enough measures in place to secure the diplomats’ servers to ensure the security of their privacy, their data, and the confidential matters that were being discussed. Logistical problems in coordination due to differences in time zones also led to delays in important discussion and the lack of timeliness of responses was a source of frustration for participants and organizers alike. For example, the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference (MC12) was originally planned to take place in Kazakhstan in June of 2020 but has now been planned for late November of 2021 after two rounds of rescheduling. The second challenge noted by participants was the format of the online meetings and lack of physical presence which complicated the organisation of training seminars and briefing sessions. The increased participation of capital-based officials hindered the focus on diplomatic topics of importance to the ambassadors interviewed who also felt that the standards and norms of regular pre-pandemic negotiation meetings could not be effectively replicated online thus causing further delays. Thirdly, challenges arising from geopolitical tensions and power struggles were further exacerbated by the virtualisation of the WTO meetings. Based on the issues discussed, the study offers recommendations for developing member states of the Commonwealth (more specifically for LDCs, SSAs, and small states) to capitalise on the advantageous opportunities of virtual meetings i.e. lower costs, environmentally friendly, greater participation, and curtail the drawbacks as much as possible. The study suggests that the ideal post-pandemic protocol for such international negotiation and discussion forums should be a mixture consisting of both in-person and virtual/online meetings, and those member states that struggle to effectively participate due to gaps in digital prowess must give priority to train their ICT and digital sector professionals to facilitate better software up-gradation and promote the use of innovative technology, such as gesture-recognition that may provide clearer body language signals and more sophisticated chat applications. If they are unable to do so effectively, they should be allowed to draft and/or amend discussion texts or agendas at asynchronous times to accommodate lags caused by slower internet speeds.

In general, due to the popularity and benefits of virtual meetings for the majority of the developed and developing states, digital means of communication will remain in place well after the pandemic. Despite the challenges faced by the aforementioned states in building the appropriate digital infrastructure, virtual and/or hybrid meetings can increase their participation in WTO discussions without burdening member states with travel costs and causing capacity issues for Geneva. The question of whether WTO’s objectives may be effectively carried through via digital communication largely depends on how swiftly they can optimise the current provisional arrangements to streamline online and/or mixed-mode meetings.

Trade measures in response to the pandemic

Many WTO members, including the G20, have administered unilateral trade policies to abate the effects of the pandemic on their economy and healthcare; from the beginning of 2020 to mid-October, around 50 of the 133 (37 per cent) trade and trade-related policies for pandemic management were trade-restrictive mostly in the form of export controls encompassing US$111 billion worth of trade. These measures have exacerbated pre-existing import restrictions placed on G20 countries since 2009 that have already affected 10.4 per cent of their imports. Overall across different periods, WTO members, including several Commonwealth states, have introduced a total of 183 trade-restrictive measures of which 93 are still in place as of March 2021 with no concrete end date in sight. This raises issues within the WTO regarding the validity of these measures as although Article XI of the GATT allows such restrictions to prevent supply shortages, these measures are only meant to be temporary and should not impose any form of discrimination that may risk the trade security of others (many of these restrictions were imposed upon medical supplies and food products). Not to mention, several of these measures were carried through without the WTO being informed despite that being a rule for WTO members, causing difficulty for other countries that were forced to make abrupt changes to their trade purchases. Aside from short term disruptions, trade restrictions of these sorts have long term repercussions on import-export prices until and unless former trade relations and favourable agreements are re-established.

Besides the direct impact of these restrictions on trade, they have also directly and indirectly affected member countries’ UN SDGs’ progress, especially for vulnerable countries. To give a non-tariff example, additional license requirements on food products during the pandemic adversely affected food-importing countries which encompassed 34 Commonwealth countries, hindering their progress on SDG 2: Zero Hunger i.e. food security and hunger alleviation. Likewise, technical barriers to trade (TBT) preconditions on medical products have affected SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth i.e. sustainable growth, by reducing pharmaceutical businesses’ earnings due to added compliance costs. Interestingly, however, this has had a positive effect on SDG 3: Good Health and Wellbeing as the stricter quality standards resulted in better quality medicine available to citizens. Another risk concerning medical products is the finite production of vaccines in complex supply chains. Whilst Commonwealth states removed all trade restriction measures by July 2020, other countries may consider export restrictions for vaccines to safe keep surplus stockpiles for their own public policy objectives, which may have dire consequences for all Commonwealth states, whether developed or developing, in being able to obtain enough vaccine doses for their citizens. Global responses to COVID-19 must include a call to lift such trade-restrictive measures which will not be feasible without international cooperation towards enabling supply chains and expediting transborder goods movement.

Commonwealth advocacy for trade facilitation and enabling supply chains

Given the large-scale disruption in cross border transport and logistics services compounded by heightened checks and balances of quarantining and social distancing measures, the movement of essential goods trade was significantly staggered. To bypass these blockades Commonwealth states introduced several digitised measures to replace traditional transborder clearance processes, a few examples of which are:

1) Joint cooperation of the Commonwealth Secretariat with the WTO and other multilateral organisations in developing the COVID-19 Trade Facilitation Repository under the WTO TFA ratified by 154 (94 per cent) members. This Repository is a comprehensive guide for policy responses to the pandemic containing all relevant material available on trade facilitation measurements.

2) The UK government’s use of temporary digitisation of customs border processes by allowing traders, agents, and Border Force staff to exchange important documents via electronic means (email, fax, digital photographs etc.).

3) The South African government permission of animal product importers to submit computerised veterinary health certificates, and further verification documents if needed by relevant authorities, to replace time-consuming hard copy application procedures.

4) The introduction of ePhyto certificates by Grenada, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago to prevent setbacks and/or lag in the exchange of fresh produce amongst each other.

5) Commonwealth members of the Asia-Pacific region’s implementation of facilitation measures to boost transparency, promote institutional coordination, and simplify transport, transit, imports, and customs protocols.

These measures have produced favourable results and their continuation post-COVID could lead to notable policy improvements and accelerated economic recovery. Other noteworthy examples of initiatives undertaken by the Commonwealth that highlight their active advocacy for open trade and complex supply chains include the Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic, issued by Singapore and New Zealand in April 2020. The two-member states committed to removing all types of export restrictions on medical and food products and increasing trade amongst each other, inviting their fellow WTO member states to partake in the agreement as well. In the following month of the same year the Commonwealth states of Australia, Canada, Malawi, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK, along with other WTO members, delivered a joint statement advising fellow members against any trade policy changes that would be damaging to trade in agricultural food products and encouraged digital trade-facilitating interventions e.g. electronic copies of certificates of origin to protect the agri-sector trade markets. Additionally, the Ottawa Group (includes Commonwealth states of Australia, Canada, Kenya, New Zealand, and Singapore) was a frontrunner in campaigning against emergency trade restriction measures during the pandemic.

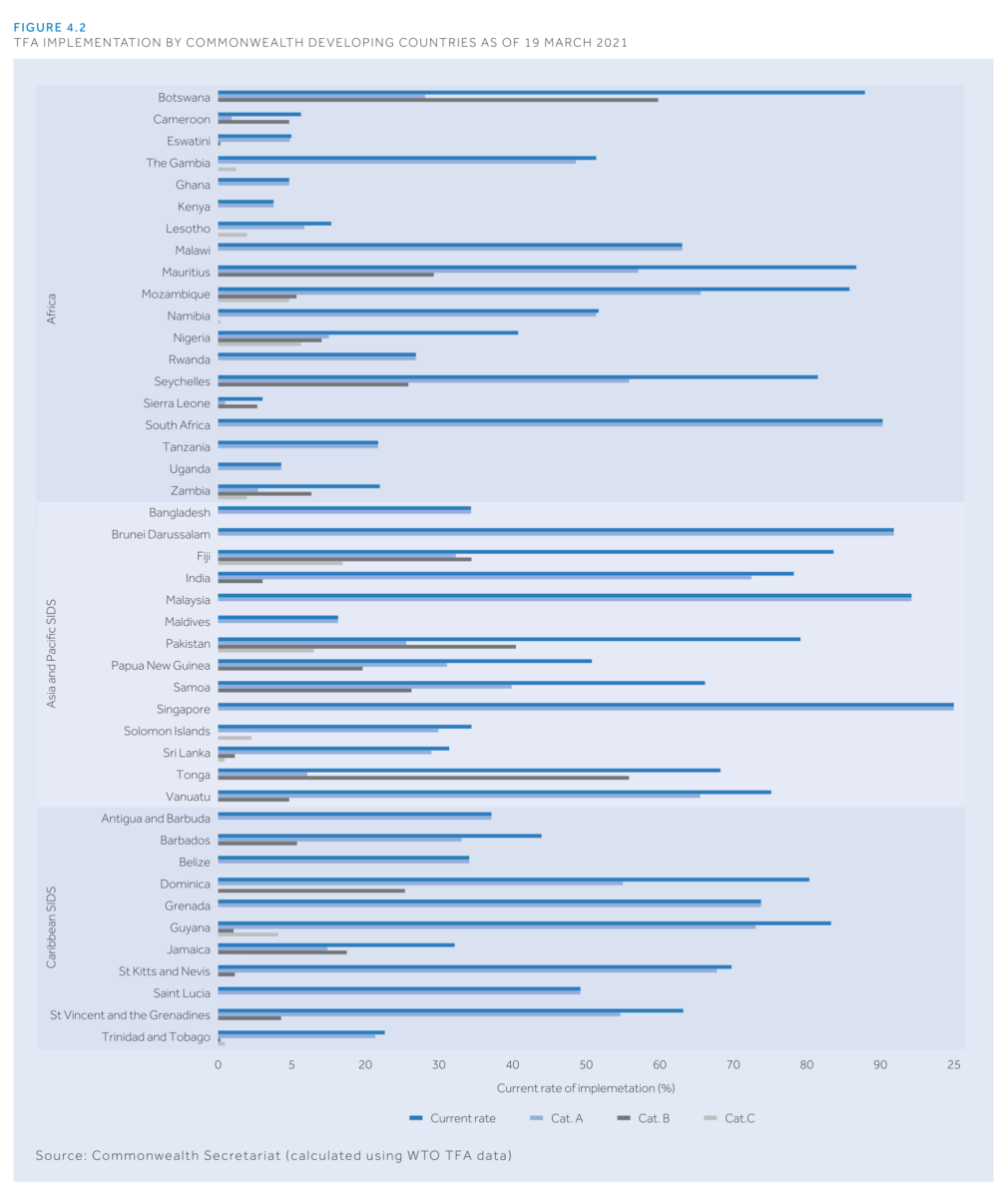

Developing and LDC member states of the Commonwealth that lag in terms of pandemic responses to enhance economic recovery, are suggested to replicate the aforementioned advocacy campaigns and consider making the improvised trade-facilitation measures adopted during the pandemic permanent. Furthermore, despite 48 of the 50 Commonwealth countries (that are members of the WTO) having ratified the TFA, the extent and rate of implementation of the agreement are quite uneven across the developing states with Singapore being the only state in the category to complete all the requirements. Including Singapore, only 17 of the 50 member states have successfully fulfilled more than half of the Category A requirements of the TFA whilst only 2 member states have fulfilled more than half of the Category B requirements. It must be clarified that the TFA acknowledges the need for technical assistance (under TFA Article 14) and more time to be allotted to developing and LDC state members for Category B capacity-building; this extended timeframe can partially explain the low implementation rate for Category C which has only been successfully implemented by LDCs Bangladesh and Rwanda (on-going Category C projects in March 2021). Additionally, although the TFA Facility has been set up by the TFA Article 14 to aid developing and LDC states in applying the TFA, the member states have flagged issues regarding the increasing difficulty in being able to secure the support. Fortunately, many Commonwealth African, Caribbean and Pacific member countries are participants of other bilateral and regional trade facilitation initiatives that provide these member states with the additional support to compensate for the lack of TFA Facility assistance.

Figure 4.2: TFA implementation by Commonwealth developing countries as of 19 March 2021

Ensuring affordable and equitable vaccine access in the Commonwealth

Besides Malta, the other 5 net-exporting countries of COVID-19 related medical supplies of the Commonwealth are located in Asia- Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, and Sri Lanka; the remaining 47 Commonwealth states rely on international trade in these goods for their consumption. Since such a few Commonwealth members can produce vaccines, the WTO’s Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health is a crucial multilateral means for the Commonwealth to gain sufficient and affordable supplies of vaccines. The 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health advocates for the WTO members’ right to use the flexibilities of the TRIPS Agreement to protect public health by being able to grant compulsory licenses via conditions they may set up themselves. In January 2017, Article 31bis was enforced to allow affordable medicine production to be exported under a compulsory license solely for those countries that are unable to produce the medical supplies themselves. Despite the presumably beneficial nature of the Agreement, the majority of the developing countries continue to face challenges for equitable access and fail to capitalise on the clausal advantages owing to factors such as political and economic pressure exerted on these developing states by industrialised economies, the complexity of applied licenses in practice, meagre institutional capacity, and lack of coordination between patenting bodies, government ministries, and regulatory authorities. Due to such obstacles, the special licensing system has been used only once since the ratification of the Agreement, and its slow pace towards satisfactory results has been widely criticised. Furthermore, finding a sufficient number of countries with the appropriate capacity and approved infrastructure to manufacture and distribute medicines on a global scale has been an arduous and unfruitful task.

As a possible solution to this deadlock, multiple Commonwealth countries of the WTO, led by India and South Africa, along with other non-Commonwealth WTO members, have asked the WTO to waive the TRIPS Agreement’s conditions regarding copyright, patents, industrial designs, and confidential information (trade secrets) amidst the pandemic until the majority of the population has built enough immunity. If permitted, the waiver would allow members of the WTO to produce and export standard vaccines at both a national and global level which will reduce access disparities and increase the likelihood of eradicating the vaccine before it has a chance to mutate into multiple, dangerous, and vaccine-immune variants. The waiver may also contribute to a healthier precedent for future emergencies and human biosecurity that will restore international confidence in the multilateral system of trade and globalisation. Despite the sizeable support for this notion, there are also a considerable number of WTO members that rebut this idea, arguing that the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health already offers sufficient flexibility within its clauses that strikes the right balance between the considerations of global public health whilst also safeguarding the intellectual property rights (IPR) holders. These contending states maintain that further flexibilities to the Agreement will complicate the already cumbersome and time-consuming process of obtaining compulsory licenses which will involve laborious negotiations over remunerations with the IPR holders that will be counterproductive to a problem as time-sensitive as the COVID-19 pandemic. Ultimately, the WTO members must hasten their progress towards reaching an agreement on how to facilitate worldwide vaccine distribution.

The Commonwealth and regional cooperation amidst a global crisis

Regional trade developments

Despite limited multilateral progress in trade development and due to deepening trade and investment relations between regional neighbours, regional trade agreements (RTA) are on the rise with 339 RTA acknowledged by the WTO as of February 2021 and several ongoing negotiations for new RTAs currently taking place. Several RTAs involving the Commonwealth states have been established in the past few years, including but not limited to the AfCFTA, the RCEP, the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER)-Plus, and multiple RTAs between the UK and other Commonwealth states that were signed post-Brexit to guarantee Britain’s counterparts of its commitment towards trade continuity and improving trade opportunities amongst each other. Due to their regional nature, RTAs surpass the WTO’s coverage of member states’ policy areas such as e-commerce, investment, competition, environment, labour standards etc. and new forms of RTAs are also on an upward trend encompassing cooperation in innovative fields e.g. the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement between New Zealand and Singapore that analysts surmise may be the first model of next-generation agreements for this field. Commonwealth Africa has been leading the way in terms of the Commonwealth trade agreements and is currently establishing reciprocal trade with the top two global economies; Mauritius having already signed an FTA with China in 2019, the latter’s first-ever, and Kenya currently in talks with the US which, if successful, would be the latter’s first FTA with an SSA country after the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and US FTA saw concluded in April 2006. Inter-regional developments are also a key avenue of multilateral activity in the Commonwealth; in December 2020, the Commonwealth members of the Organisation of African, Caribbean, and Pacific States (OACPS) and the EU, inclusive of the two Commonwealth Europe states of Malta and the UK, announced the end of the Cotonou Agreement and vowed to replace it with a new agreement with a more holistic approach. As of April 2021, the negotiations have concluded and the new agreement will be announced soon.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the majority of the Commonwealth trade occurs regionally, meaning that RTAs have a considerable impact on Commonwealth trade, even more so than the WTO according to the Commonwealth Secretariat. This is backed by studies that find trade between Commonwealth states to be triple in value (356 per cent) if they happen to be participants of the same trade agreement. As more agreements are being notified to the WTO, the Commonwealth countries continue to pen down more RTAs that will be useful for trade recovery post-COVID-19. Africa, for example, has signed the highest number of RTAs in the bloc with some countries of the region belonging to two or more agreements at a time. An increasing number of RTAs in the Asia-Pacific is enhancing trade complexity in the region as agreements begin to overlap amongst each other. However, this multi-RTA membership creates what is known as the “spaghetti bowl” effect which may risk complicating trade rules and regulations subsequently confusing businesses and potentially hiking up costs, especially for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) who must comply with multiple rules of origin (RoO) to enjoy tariff preferences. To avoid adverse effects, mega-regionals such as the AfCFTA and RCEP may be effective in rationalising the RTAs by standardising rules and regulations as well as facilitating more countries’ participation in these networks, especially post-COVID-19. These two mega RTAs are the largest of their kind in terms of economic size and the number of participant countries.

The AfCFTA: The game changer for Africa’s Global and Intercontinental Trade

The AfCFTA is a single market platform for goods and services allowing free movement of businesspersons and investments for 54 out of 55 African Union (AU) states. Although enforced on 30 May 2019, the RTA faced a 6-month delay and began on 1 January 2021 following the onset of the pandemic with Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa being among the first members to trade on the new basis of preferences. The most important element of the AfCFTA is its prioritisation of benefitting SMEs which comprise more than 50 per cent of the entire African region’s GDP and is responsible for above 80 per cent of the region’s employment, creating lucrative trade opportunities for market expansion, most notably for food products, services, and basic manufactures. Notwithstanding the advantages, most African states customarily rely on exports outside their continent; in 2018, intra-African trade constituted 15 per cent of the region’s total, far lower than the averages of Asia (60 per cent) and Europe (80 per cent) that year. As of yet, the 19 Commonwealth SSA states, who currently have a 55 per cent share of intra-African trade, are in place to benefit the most from this Agreement; whereas the Commonwealth LDCs, who have been given a longer implementation period with bigger carve-outs set aside for sensitive products compared to other members (10 years vs 5 years to reach 90 per cent liberalisation; 13 years to reduce tariffs on sensitive products vs 10 for non-LDCs), have yet to maximise the Agreement’s potential for their trade growth.

Provided the members of the AfCFTA remain determined to engage each other within the Agreement, it has the potential to increase intra-African trade to above 25 per cent within the next 10 years. Studies show that the elimination of non-tariff barriers and prioritisation of building productive capacity, boosting regional value chains, and investing in infrastructure within the continent will bring about an even higher percentage increase of intra-African trade and may even help bridge the US$60-90 billion infrastructure gap.

Commonwealth and the RCEP: Trade and Investment implications

Representing one-third of the global population, 30 per cent of the global GDP, and 30 per cent of the Commonwealth’s global merchandise exports, the RCEP is currently set to be the largest trading bloc in the world. The agreement was ratified in November of 2020 and is expected to take effect on 1 January 2022. Of its 15 members, 5 are the Commonwealth states of Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Singapore; India underwent the negotiation process but ultimately withdrew its application in 2019, reportedly due to concerns regarding lack of better service access and appropriate mechanisms to safeguard its economy from the risks of lower tariffs on local producers. The most attractive element of the RCEP is its harmonisation and simplification of the RoO of existing FTAs, creating a single intermediary goods market that will boost intermediate product trade and further integrate and diversify regional supply chains, which may be particularly beneficial to the GVCs of the two Commonwealth states of Malaysia and Singapore. Furthermore, participants of the RCEP that have comparatively lower labour and production costs may use the platform to draw multinational enterprises looking to invest and establish new supply chains in lower costing locations within the region.

The RCEP also does not have adverse implications for Commonwealth states outside its jurisdiction; it will undoubtedly benefit the South Asian member states of India, Bangladesh, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka due to their robust trade relations with their RCEP signatory counterparts. Equally, the Commonwealth small states and LDCs are also less likely to be affected due to their strong ties with Australia and New Zealand. To ensure maximisation of profit from the bloc, signatories are advised to navigate trade relations within the Agreement whilst being aware of geopolitical issues stemming from tense security relationships between member states; the most prime example being the tensions between Australia and China due to the latter’s ban of the former’s beef, wine, timber, and coal (amongst other goods) imports for political reasons. The rudimentary and rather narrow scope of the RCEP’s dispute settlement apparatus can not be relied upon as a potential solution to these obstacles as of yet but maybe a potential solution if developed.

Mega-regional FTA implementation: Reshaping the trading landscape

Upon full actualisation of these two RTAs as well as other mega-regionals such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the global trading arena may be significantly revamped and these RTAs may catalyse trade expansion to bring about advantages for members and non-members alike. This reshaping will, however, come at a cost; for members, the price may involve adjustment costs incurred due to tariff removal and new trade rules as well as new standards. For non-members, aside from the costs due to new rules and regulations, they may have to deal with global diversion of trade and investments. As such, vulnerable countries of the Commonwealth developing and LDC states are advised to actively fortify their productive capacities to be able to comply with the new standards and requirements of global trade using multilateral and bilateral assistance under the WTO’s Aid for Trade initiative. The Aid for Trade Initiative may also aid developing Commonwealth states in cushioning costs incurred through trade deal implementation processes i.e. supply response generation and domestic adjustments. These states are recommended to equally distribute investment into both “hard” and “soft” infrastructure by building stakeholder awareness and capacity with special emphasis and preference for women-led MSMEs. The LDCs can also rely on the Enhanced Integrated Framework for LDCs and the United Nations Technology Bank for LDCs to negate such costs incurred at a better rate than their more developed Commonwealth members. To ensure that these new protocols are streamlined and effectively supervised, governments of RTA members should deliberate introducing multi-faceted work programmes under institutions, equipped with generous budgets and financial backing, that are solely tasked to guide trade agreement implementation.

Enforcement of existing RTAs that have not been fully utilised, including those with global non-Commonwealth partners, could be a key stimulus for economic recovery during this COVID-19 period, especially Commonwealth LDC and developing countries that struggle with restricted fiscal space. This may also be a crucial catalyst for the transborder exchange of essential goods, food, and pharmaceuticals. RTA enforcement must not limit its focus to lowering tariffs and expanding tariff preferences because deeper integration of behind-the-border measures, improving cross-border transport and logistical infrastructure, reduction of trade costs via simplification of border protocols (e.g. Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement), and structural transformation of regional value chains are non-exhaustive examples of non-tariff changes that will result in greater trade and investment generation than simple tariff reductions. Since new trade agreements generally take long periods (i.e. decades) the benefits are not accessible until much later. For example, the Caribbean Forum (CARIFORUM) Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with the EU is the sole EPA that covers the services industry which secured significant gains relative to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS); however, the Caribbean side of service suppliers, especially those in the entertainment industry (artists, performers, cultural service providers etc.) have not been able to optimise benefits due to barriers related to mutual recognition of standards plus the difficulties they face in securing visas. This may be partially solved in this post-Brexit era wherein the UK’s relations with CARIFORUM may be able to deliver more meaningful market access, especially since such a large Caribbean diaspora dwells within the European country.

Regional cooperation during COVID-19

Africa:

With the support of the AU Commission and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, African countries have made an impressive collective front against the COVID-19 pandemic by addressing medical supply shortages and striving to procure enough vaccines for all eligible citizens across the continent. The African Medical Supplies Platform (ASMP), which includes all AU members along with the 15 member states of CARICOM that belong to the Commonwealth, is a non-profit initiative set up in June 2020 as a collective funding pool dedicated to purchasing medical supplies and consolidating the continent’s purchasing power amidst the economic crises. By mid-January of 2021, the ASMP launched the COVID-19 Vaccine Pre-Order Programme under which a new category termed “vaccine accessories” was made to facilitate the distribution of ultra-low temperature freezers, syringes, vacuum-sealed containers among many more instruments required for vaccine storage and handling.

Furthermore, the AU created the Africa Vaccine Acquisition TaskTeam to guarantee that the member African countries were being provided with enough vaccines to reach a target of 60 per cent immunisation of the continent’s population. In efforts to bolster the continent’s crisis management, several Commonwealth African states repurposed manufacturing capacity and infrastructure into medical facilities to support the national and continental healthcare sectors. The African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) has been another key provider of support to the continent’s countries in times of economic crisis, not just via concessionary export financing but also through its support for the broader development of intra-African trade. COVID-19 has been no exception, the Afreximbank permitted the use of its facilities to fund imports of crucial medical goods and vaccines; it signed off US$100 million to the ASMP initially, adding another US$2 billion for the procurement of vaccines for the AU countries via the ASMP single-source platform.

Asia:

The South Asian countries have been leading the continent’s united front against the pandemic; in March 2020, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), besides creating a website to track the pandemic’s development across the region, hosted a high-level meeting, the first since 2014, during which an emergency fund of over US$18 million was created, US$16.5 million of which was donated by the 3 Commonwealth Asian states of Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka. Of this donation by the Commonwealth states, India provided US$10 million and also provided online training to emergency responders, set up a surveillance platform for outbreak management, as well as masks and other direly needed medical equipment to the most heavily affected countries. India is one of the select Commonwealth developing countries with the ability, and facilities, to develop and manufacture quality vaccines. By volume of vaccine manufacturing, the Serum Institute of India ranks first, having produced over 100 million Covishield vaccines by June 2021[1].

Caribbean:

On 21 January 2020, the Caribbean Public Health Agency (CARPHA) dispatched its Incident Management Team-Emergency Response and the Regional Coordinating Mechanism for Health Security (RCM-HS) in response to the onset of the pandemic. The two bodies are responsible for providing the region’s governments guidelines on virus containment, training local health care workers, and securing sufficient stocks of masks, test kits, and other medical necessities. In April of the same year, the CARICOM Heads of Government convened to consult international finance bodies together, seeking fiscal support and urging donors to incorporate additional factors into consideration for their aid donations, giving special focus to the vulnerability of the Caribbean countries relative to the performance of other regions.

In October 2020, CARPHA partnered with the Pan-American Health Organisation and several more international health institutions to maximise the region’s mobility against the virus. Due to the reliance of the region’s economy on tourism and the gradual decrease in the number of cases due to effective social distancing measures, CARPHA introduced precautionary protocols to assist secure reopening of borders and the resumption of economic activities.

Pacific:

To support the Pacific region’s fight to contain the rapidly deteriorating conditions as a result of COVID-19, the Pacific Humanitarian Pathway for COVID-19 (PHP-C) was set up in April 2020. Its primary objective is to supervise specific areas impacted by the closing of, or restrictions upon, border activities; namely, the dispatchment of technical personnel to and from Forum Island Countries (FIC); repatriation of FIC nationals to their residences; biosecurity during immigration and customs; and the clearance and decontamination of planes and ships transporting medical aid, technical personnel, and FIC nationals. The provision of medical and humanitarian aid for the FICs is sought by the PHP-C from regional as well as international developmental partners via channels such as the Pacific Cooperation Foundation.

Via the World Food Programme, Australia contributed US$5.5 million to the PHP-C, of which US$4 million was allotted to aviatory delivery of crucial medical supplies and logistical assessment of the pandemic’s adverse effects on the region’s food security. Australia pledged further support to the Pacific countries’ drive for vaccine procurement by providing US$80 million to the COVAX Facility Advance Market Commitment via its Partnership for Recovery Strategy. Over the coming two years as part of the Pacific-Step-up initiative, Australia also plans to set up a COVID-19 Recovery Fund worth US$304.7 million to reverse the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic.

These actions highlight the importance of regional cooperation amidst global health crises, playing a key part in the economic recovery of Commonwealth states.

Leveraging RTAs for a robust recovery

To build back better, RTAs may prove to be one of the most beneficial long term avenues for sustainable and resilient economic recovery. Existing agreements must be fortified and reviewed and future negotiations must be based on strict provisions of equity and safeguarding of vulnerable economies. This Trade Review provides policymakers with three focus areas to equip Commonwealth states with the right tools for RTA maximisation:

1) Strengthen RTA provisions to enable cooperation amidst global crises:

Such trade agreements may be great conductors of regional trade for essential food and medical goods as they can reduce tariffs, administrative fees, and domestic taxes on these trade inflows, and also play a role in digitising cross-border processing systems to replace the paper-based and time-consuming protocols. To guarantee the streamlining of these RTAs, governments must be mindful to adhere to their obligations of transparency to the WTO, consistently publishing detailed reports on their pandemic response policies. An opportunity to improve the rules and norms of existing, and under negotiation, RTAs is the development of model provisions promoting deeper trade cooperation and coordination amidst economic and health crises, such as for arrangements on the exchange of medical goods, health care, sanitary and phytosanitary standards and food security while enhancing crisis conformity assessments and reviewing technical barriers to trade to equally benefit both (or all) parties involved in the trade.

2) Harness trade agreements as tools for inclusive recovery:

Inclusive recovery calls for the impact of marginalised demographics- women, handicapped, and disadvantaged as workers, traders, and consumers- to be considered and mainstreamed as COVID-19 has had particularly negative effects on sectors that employ these workers including the garments, tourism, and hospitality industries, more notably so in the Commonwealth small states, LDCs, and SIDS. Despite the fact that women comprise the largest share of informal cross-border traders, most RTAs do not consider these activities. As such, it is strongly recommended that provisions to support women entrepreneurs and their businesses impaired by the pandemic be implemented promptly to connect these businesswomen to the global economy. Taking the AfCFTA for instance, the negotiations currently underway of schedules for goods, services, and future e-commerce platforms present a good opportunity to bring issues faced by women to the forefront of the agenda. This will allow flexibility in the scheduling of countries’ commitment to the RTAs providing adequate policymaking leeway to accommodate and support gender-sensitive infant sectors via longer timeframes for liberalisation and simultaneously opening others to increase competitiveness. Current plurilateral discussions at the WTO may also be useful for policymakers to learn how to ameliorate current domestic regulation policies to favour and support women’s economic empowerment.

3) Build regional production and supply chains:

Amidst the havoc wreaked by the pandemic, global economies faced an alarming shortage of medical and essential supplies forcing them to over-rely on single suppliers while dealing with numerous export controls. The challenges weathered in the past two years to revive the global economy have tilted many nations, especially advanced economies, towards unilateral and self-preserving policies. The rise of “vaccine nationalism”, whereby states hoard surplus stockpiles of vaccines, and the rekindled fervour for the reshoring and shortening of global supply chains is presenting as a more attractive option than multilateralism for advanced economies that have the financial and technological ability to produce essential goods and services within their borders. For the majority of the Commonwealth states, such autarkic frameworks would be quite disadvantageous, impractical and frankly unfeasible. To counteract the growing unilateralism across the international arena, Commonwealth states, particularly the vulnerable member nations in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, must actively push for regional solutions to these global crises. This may include regional accumulation of essential wares for future global shortages and bolster regional production by adding value to current manufacturing inputs. Furthermore, increasing collaboration with regional partners in boosting regional value chains that may lessen member states’ economic vulnerability and further accelerate industrial development for those states that struggle with gaps in infrastructure and facilities. In addition, these regional value chains, if sufficiently expanded, could assist Commonwealth African states in weaning off their dependency on global partners outside Africa to better position themselves for potential global shocks in the future.

“Factory Southern Africa”

Case studies of the Southern African nations highlight golden opportunities to expand their manufacturing bases along with their proactive capacities. Amongst these countries, South Africa holds an advantageous position in terms of participation in GVCs across sectors ranging from agriculture to mining and finance, entailing South Africa’s crucial role in driving the creation of Southern Africa’s cross-country value chains. Consequently, this implies a complementary role to be played by South Africa’s counterparts in the region to support these new value chains as well as increasing linkages with South Africa’s existing GVCs.

A 2019 study determines “lead products” and intermediate products exported by South Africa that have the potential to link other South African countries with South Africa’s GVCs by supplying more competitive inputs; Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and, although less so, Mozambique present consistently competitive intermediate products in the production of the top lead products exported by South Africa such as capital goods, machinery, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods and agro-processing products. Attention will be required in guaranteeing enhanced productivity as these countries are not yet capable of integrating into South African lead export GVCs, and it must be ensured that they are not ousted entirely from regional value chains in development in South Africa. Digital technologies may be employed to accelerate productivity building and product sophistication. This is complimentary to supplier development programmes supervised by South Africa’s lead firms that are mentoring regional suppliers so they may reach the desired quality requirements.

Generally, there is an overall aim to deepen regional integration of Southern Africa to holistically facilitate these regional value chains, which should prioritise the elimination of any surviving non-tariff barriers still disrupting regional trade flows, including but not limited to restrictive RoO, import bans, quotas and levies. Due attention should also be given to the harmonisation of standards and licensing requirements.

[1]https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/serum-institute-produces-over-100-million-covishield-doses-in-june-121062700594_1.html