COVID-19’s impact on Commonwealth FDI

COVID-19’s impact on Commonwealth FDI

Pre-Pandemic Commonwealth Investment Trends

The importance of foreign direct investment (FDI) for both intra-and-extra Commonwealth trade cannot be overstated, especially concerning global value chains (GVCs) structure and operations. FDI supports domestic firm participation in global networks of production and provides a channel for them to gain access to international markets partially via facilitating their integration into trans-border supply chains. FDI also has the potential to elevate export sophistication and diversification for both intensive and extensive margins. The importance of FDI also reaches beyond the dimensions of trade; contributing to the strength of Commonwealth countries’ economies by generating more jobs by encouraging skills and technology transfers between members and non-members, creating more job opportunities, and building capacity for when domestic capital and savings reserves to finance investments deplete. Technology and skills transfer facilitated by FDI can upgrade a state’s higher-value-added production and firm-level productivity, which in turn may lead to better work environments and improve job wages. However, it must be highlighted that such benefits may only be achieved if host countries implement comprehensive policies and properly facilitate and utilise FDI inflows to retain a good reputation amongst foreign investors.

Global FDI inflows into the Commonwealth

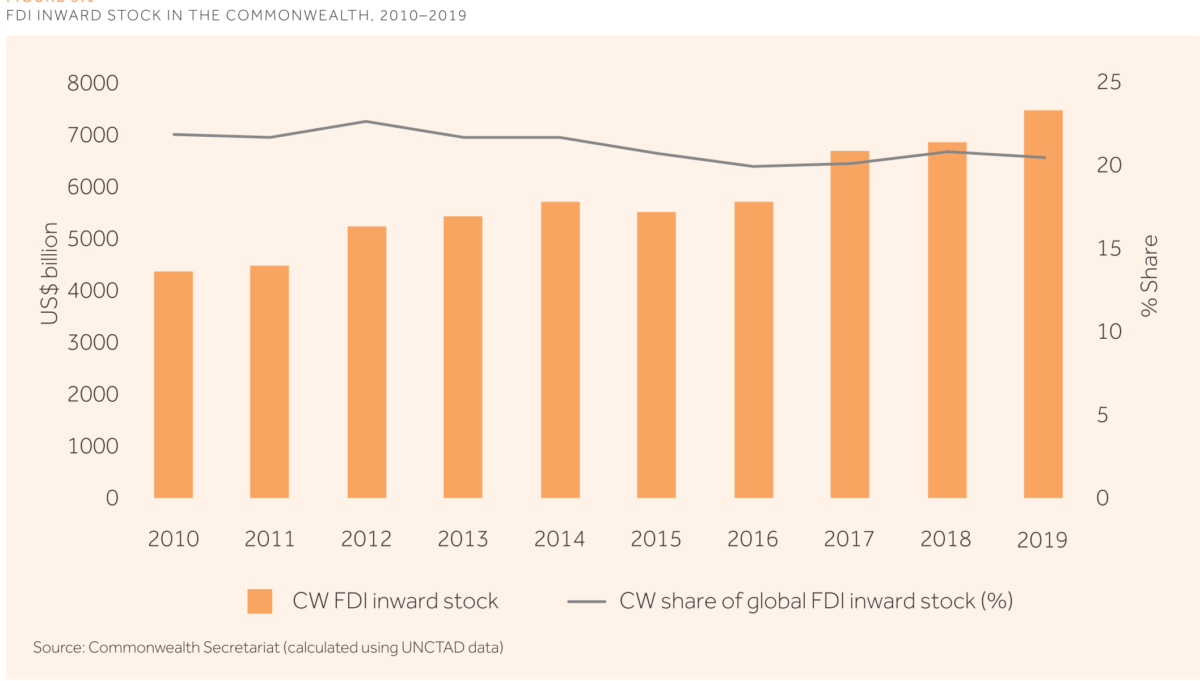

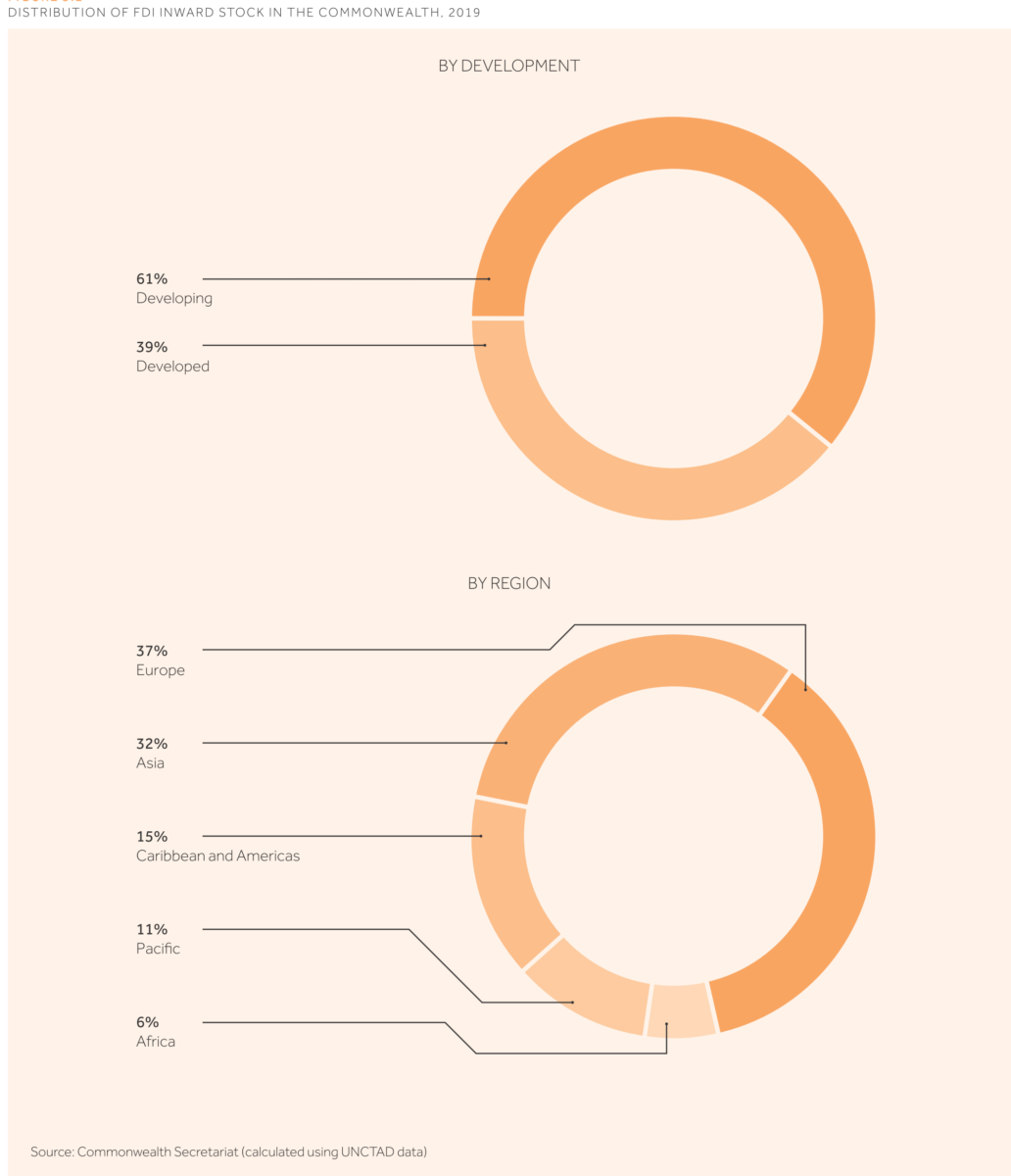

Global FDI inflows in 2019 were pegged at an estimated value of US$1.5 trillion, although slightly higher than the 2018 value of US$1.43 trillion, it was still a lower value than the 2015 estimate of 2.0 trillion and only a 0.3 trillion dollar increase from the 2009 value of US$1.2 trillion level (right after the global financial crisis). The reasons behind the decelerated growth may be attributed to delays in implementing existing investment projects, postponement of investments in the pipeline, and diminishing equity capital flows reinvested earnings. The Commonwealth’s collective FDI inward stock for 2019 summed up to US$7.5 trillion [Figure 1], almost double the 2010 value of US$4.4 trillion; despite the absolute value increase, the share of the Commonwealth in the global FDI stock has decreased 1.5 per cent down to 20.4 per cent. The bloc has performed better when it comes to annual FDI inflows; the growth rate of 6.1 per cent is notably higher than the global average of 2.4 per cent and the Commonwealth’s share in annual global FDI inflows has been steadily rising, increasing from 20.5 per cent in 2010 to 23.3 per cent in 2019. 60 per cent of the bloc’s FDI went to the developed member states. Regionally, Commonwealth Europe (UK, Malta, and Cyprus) has the highest share (37 per cent), followed by Asia (32 per cent), the Caribbean and Americas (15 per cent), the Pacific (11 per cent), and the smallest share going to Commonwealth Africa (per cent) [Figure 2]. The Commonwealth small states together hosted 10.3 per cent of the bloc’s total inward stock by 2019, with the LDCs’ share being a mere 1.7 per cent. From 2017-2019, 80 per cent of the three years’ combined amount of FDI inflows went to only five countries that were Singapore (23.9 per cent), the UK (21.1 per cent), Australia (14 per cent), India (12.4 per cent), and Canada (11.2 per cent) highlight the asymmetry in the allocation of Commonwealth investment flows in its member states.

Figure 1: FDI inward stock in the Commonwealth, 2010-2019

Figure 2: Distribution of FDI inward stock in the Commonwealth, 2019

Intra-Commonwealth FDI

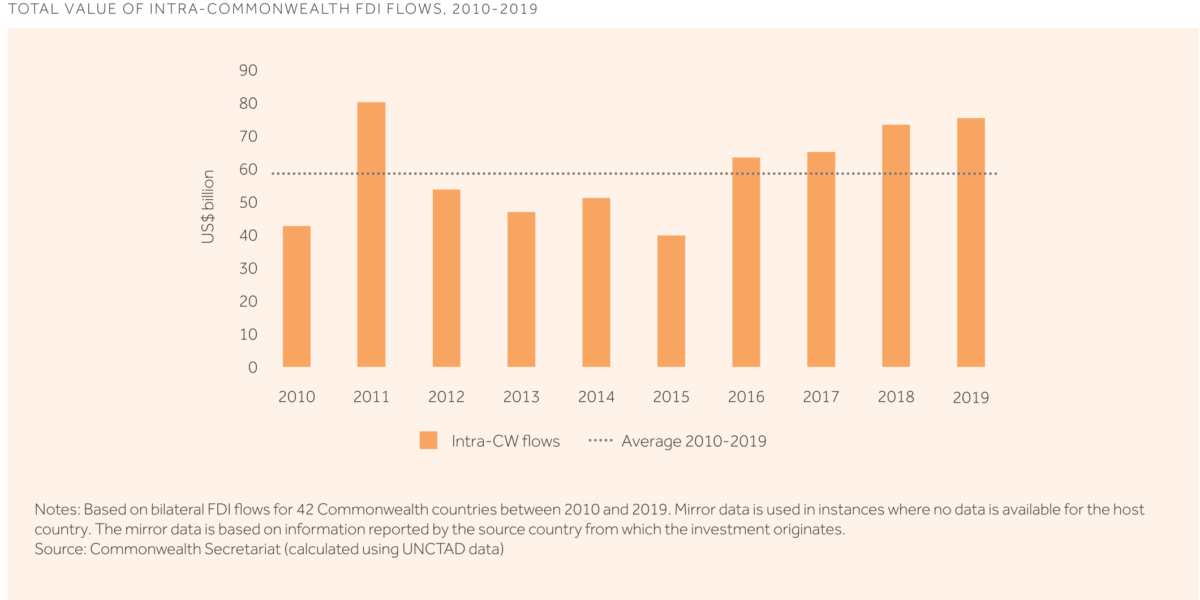

Of the US$7.5 trillion FDI stock, US$1.2 trillion (16 per cent) of the value is intra-Commonwealth. The intra-Commonwealth stock has also almost doubled since 2010 when it was pegged at US$693 billion yet despite the hike in absolute value, the share declined from 19.6 per cent in 2010 to 18.2 per cent in 2019. In addition, the intra-bloc FDI stock, too, is concentrated in a few member states namely Singapore (20.3 per cent), India (16.6 per cent), and Australia (13.3 per cent) though the list of top-ranking FDI hosts is more diverse compared to the bloc’s global FDI stocks allocation as it includes Mauritius (9.4 per cent), South Africa (4.5 per cent), Barbados (3.8 per cent), and Malaysia (3.5 per cent). These developing countries’ share outweighed the combined share of the three developed economies of the UK, Canada and New Zealand (collectively 15.7 per cent). According to UNCTAD data analysing bilateral FDI inflows of 42 member countries, intra-Commonwealth annual FDI inflows have steadily risen over the past decade (consecutively since 2015) reaching US$75.2 billion in 2019 from US$42.6 billion in 2010 [Figure 3]. Since 2017-2019, outward investments from the UK, Canada, Singapore and Mauritius constituted 90 per cent of intra-Commonwealth outflows while 86 per cent of all intra-Commonwealth FDI inflows went to India, Australia, Canada, the UK, and Singapore with Barbados, Malaysia, South Africa and Bangladesh were amongst the top 10 recipients.

Figure 3: Total value of Intra-Commonwealth FDI flows, 2010-2019

Intra-Commonwealth Investment Advantage

In the 2015 edition of the Commonwealth Trade Review studies analysing data from 2000 to 2018 revealed a “Commonwealth Advantage” as an important constituent of both intra-and-extra Commonwealth FDI inflows. Commonwealth country pairs draw 10 per cent more FDI on average compared to non-Commonwealth country pairs and investment flows between two member states is calculated to be 27.4 per cent higher for member states pairs compared to non-member states pairs. The reasoning behind the advantage is identical to those that constitute the overall Commonwealth advantage discussed in Chapter 1; English being a common language is the leading cause contributing a 9 per cent increase to FDI flows, along with similar legal systems and FTA memberships, and proximity of regional member states with each other (many member states share borders with other member states). Looking into specific types of investments it was found that greenfield investments transactions between Commonwealth countries on average are 19 per cent higher; interestingly, this effect is stronger than the aforementioned average percentage in Africa as the region draws 37 per cent more greenfield FDI than non-member country pairs.

Productive greenfield investment trends in the Commonwealth

Between 2010 and 2019, the average yearly greenfield FDI to Commonwealth countries was US$145.3 billion majorities of which came from outside the bloc whilst the intra-Commonwealth share of these investments declined during the decade by 20 per cent to 15 per cent (26.6 per cent) in 2019. These figures do not reflect the full extent of the Commonwealth advantage since 61 per cent of these greenfield FDI inflows into the Commonwealth originate from non-Commonwealth countries namely the United States (27 per cent), China (12 per cent), Japan (8 per cent), German (8 per cent), and The Netherlands (6 per cent). Commonwealth region-wise, Asia received the largest portion of 2010-2019 cumulative greenfield investments (approx. 33 per cent) followed by Africa (28 per cent) and Pacific (20 per cent) while the lowest shares went to Europe (13 per cent) and the Caribbean and Americas (5 per cent). Greenfield FDI has been a vital fount of new jobs for the Commonwealth this past decade, contributing 4,839,341 jobs across the bloc 20 per cent of which were created via intra-Commonwealth investments meaning, on average, 2.3 jobs were generated per US$1 million in intra-Commonwealth greenfield FDI. For 2017-2019, the developed member states accounted for 57 per cent of announced greenfield projects in other member countries led by the UK that contributed almost one-third of the total intra-Commonwealth greenfield FDI share at US$24.1 billion with 79,414 jobs created. The main developing member sources of such investment were Singapore, South Africa, India, Malaysia and also Bangladesh. Bangladesh is a note-worthy case of an LDC greenfield investor; between 2017 and 2019, most of the country’s greenfield FDI outflows went to India (US$1.1 billion in terms of value) of which 90 per cent was dedicated to coal, oil and gas projects whilst the remaining was used on financial services, transportation and warehousing, and plastics. Bangladesh also contributed US$140 million to Kenya’s metal and pharmaceuticals projects, US$56 million into Malaysia’s pharmaceutical sector, and US$9.5 million in South Africa’s financial services.

70 per cent of intra-bloc greenfield FDI went into the services sector of which the largest portion (35 per cent) went to real estate followed by ICT and financial services plus renewable energy. The renewable energy sector, in particular, has seen a steady rise in investment in the share of renewable and clean energy projects amidst a strong global consensus to pivot towards prioritising sustainable development. In 2019, 516 projects in foreign countries were launched globally by renewable energy firms of a combined value of US$92.1 billion, an increase of 38 per cent compared to 2018 levels. The renewable energy sector received the second-highest amount of total greenfield FDI in the Commonwealth, growing announced investment inflows by 179 per cent at a value of US$26 billion compared to 2010 values and increasing its share to 14.8 per cent in 2019 as compared to 4.4 per cent in 2010. Intra-Commonwealth greenfield investments into the renewable energy sector are also following this upward trend, with the sector receiving the fourth-highest amount of these inflows in 2019 growing by 152 per cent compared to 2010 levels at a value of US$2.9 billion via capital investments in announced projects due to which the sector’s share of intra-bloc greenfield FDI rose from 1.6 per cent in 2010 to 11 per cent in 2019. However, in regards to both investing and hosting, these intra-bloc greenfield FDI flows are consistently saturated in a few countries; more than 70 per cent of these investment flows came from the UK, Canada and India while Australia (32 per cent), Nigeria (21.4 per cent), India (19.2 per cent), and the UK (11 per cent) received 80 per cent of these investments; although Pakistan, South Africa, and Kenya have been steadily increasing their share as well as LDCs Zambia, Bangladesh, and Tanzania.

Although global investments have been hindered by COVID-19, efficient and productive investments in the renewable energy sector will create sustainable post-pandemic economic and environmental benefits that may help reduce the usage of fossil fuels and lower air pollution, which is crucial for the well-being of Commonwealth members, and create employment opportunities especially for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Besides renewable energy, the manufacturing sector drew 23 per cent of this type of intra-Commonwealth investment inflows, the largest shares of which went to the food and beverages, metals, and chemicals industries. The relatively smallest shares (7 per cent) went to the primary sector, with an overwhelming 96 per cent of this investment in 2017-2019 going into coal, oil and gas. Regionally, services constituted 90 per cent of greenfield investment inflows to Commonwealth Europe, 82 per cent in Pacific members, 67 per cent in Asia, 63 per cent in the Caribbean and Americas and 45 per cent in the African members. For Commonwealth Asia and Europe, real estate attracted the most inflows whilst for the Pacific, the renewable energy sector emerged as the most attractive, and the ICT services sector gained the most inflows in both Africa and the Caribbean and the Americas. The manufacturing sector was more salient in terms of intra-Commonwealth greenfield FDI for Commonwealth Caribbean and Americas compared to other regions, as it contributed 37 per cent of the region’s total investment inflows although a major portion of these was distributed solely to Canada and partially to Antigua and Barbuda and Barbados. Of these investments, the most sizable shares went to electronic components and metals.

Commonwealth FDI and COVID-19

Impact of COVID-19 on investment into female owned businesses

The coronavirus pandemic has devastated all types and aspects of global FDI as total inflows to the Commonwealth fell by US$153 billion and intra-Commonwealth flows fell by US$8.3 billion in 2020, entailing dire consequences for the Commonwealth’s trade due to the importance of FDI as an element of trade performance (as mentioned in section 3.1). These effects have also shown evidence of increasing gender disparity in investment opportunities. Sectors such as textiles and garments, food and beverages, hospitality, tourism, and entertainment that are more women-dominated have been some of the most adversely affected and some studies even suggest that twice as many women as men have lost their jobs during the pandemic. Additionally, the pandemic is aggravating the financial gap in funding available to women-owned MSMEs that was already pegged at a staggering US$1.5 trillion before the onset of the virus. The IMF warns that further neglect in finding solutions for these challenges during the pandemic may erase three decades’ worth of economic progress contributed by the global female population. Tackling the gender disparity and providing innovative financial instruments should be a high priority objective for policymakers worldwide to expand women entrepreneurs’ access to investment for post-pandemic recovery. According to the UN, possible plans of action include tax incentives dedicated to increasing investment in women-led businesses, supporting female angel and venture capital investors in their endeavours to discover more private capital sources, and provide women in the digital economy a comparative advantage at least initially to gain more access into the increasingly competitive market for digital finance products and services.

COVID-19 and Commonwealth’s total FDI inflows

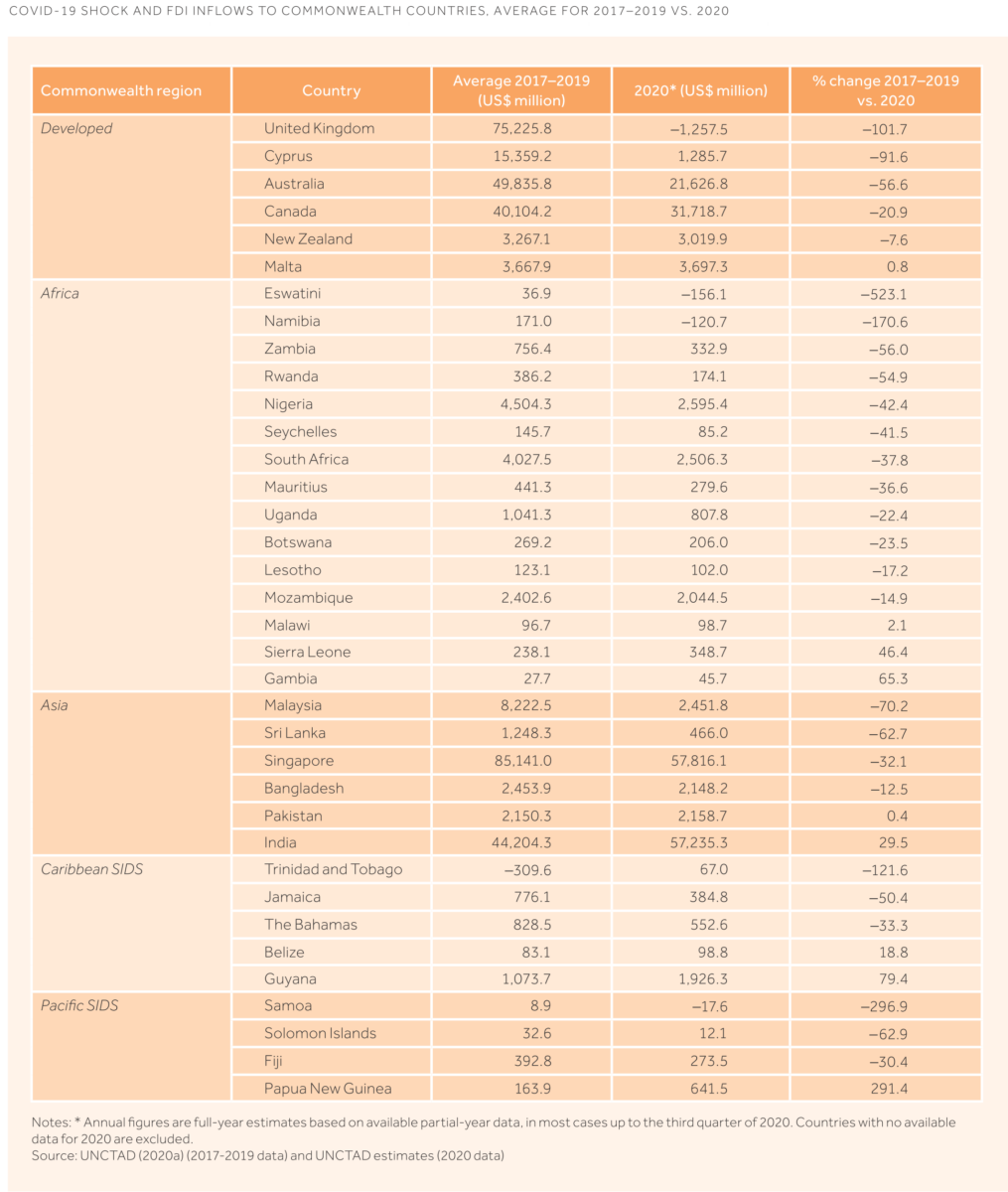

Using UNCTAD databases, this trade review analysed the 2020 FDI inflows of 36 member countries and compared them to pre-pandemic annual FDI inflows between 2017 and 2019 [Figure 4], to portray as accurately as possible the effects COVID-19 has had on the Commonwealth FDI. According to this data, globally developed countries’ FDI inflows were particularly affected by the pandemic and the Commonwealth developed members have been no exception; the UK witnessed a loss of more than 100 per cent due to divestments and negative intra-company loans with FDI inflows falling from US$75 billion to negative US$1.3 billion whilst Cyprus experienced a sharp decline of US$14 billion relative to their 2017-2019 averages falling to a value of US$1.3 billion. Inflows to Australia were halved and Canada’s FDI dipped by 21 per cent (US$8 billion) partially due to the halving of new investments in their multinational enterprises (MNEs) located in the United States. Although Malta did not suffer from FDI inflows declining into negatives and registered a positive growth of US$29 million compared to the average of the three preceding years, the growth is rather marginal and undoubtedly would have been higher had it not been for the pandemic. The decline in the demand and prices of commodities in the Q1 and Q2 of 2020 had already left the African economies vulnerable and the decline in project financing and FDI inflows by the second half of the year only worsened the region’s situation with African LDCs and SIDS being amongst the globally worst affected; Rwanda’s and Zambia’s FDI inflows were more than halved, falling by 55 and 56 per cent respectively while Seychelles’ fell by 42 per cent and Mauritius by 37 per cent. South Africa and Nigeria, two of the region’s largest economies, were also heavily affected, both suffering a loss of an estimated 40 per cent translating to a deduction of US$1.5 billion and US$1.9 billion respectively with the closure of oil-sites and lowering crude oil prices being a key factor for the latter’s loss in FDI. Relative to other member states in the region, Botswana, Lesotho and Mozambique were more insulated against global FDI drops due to ongoing project implementations and the three African LDCs- The Gambia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone- registered minimal positive growth similar to Cyprus.

Figure 4: COVID-19 shock and FDI inflows to Commonwealth countries, average for 2017-2019 vs 2020

Singapore, being one of the largest FDI recipients in Asia throughout the decade, saw inflows decrease by a staggering US$27.3 billion (32 per cent) in 2020 largely due to steep declines in cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As) but the most affected economies of Asia in the recorded database were Malaysia and Sri Lanka whose inflows contracted by 70.2 per cent (US$5.8 billion) and 63 per cent (US$0.8 billion) respectively. FDI inflows of these two countries along with Bangladesh (which’s FDI inflows contracted by 12.5 per cent) were significantly affected by the disruption of apparel manufacturing GVCs and global demand for textiles and apparel which are leading exports for these member states. Long term negative effects on these countries’ manufacturing sector may significantly hinder their export outlooks, especially due to pre-pandemic and ongoing debates over increasing re-shoring and shortening value chains that will shift focus to regional market-seeking FDI. India was the only member state of the region to completely go against the global downward trend in FDI, registering instead a positive growth of 30 per cent (US$13 billion). The reason for India’s outstanding performance can be attributed to investments into its digital and consulting sectors, both of which saw above-average growth during the pandemic due to physical and travel restrictions, as well as lucrative M&A deals in its energy and infrastructure projects. The Caribbean SIDS, the only Commonwealth category for which all members have full-year FDI inflows estimate for 2020 available, were fared slightly better than their regional counterparts; although Jamaica and The Bahamas saw their net inflows decrease by 50 per cent and 33 per cent respectively, Belize, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago all registered positive increase in their inflows, especially Trinidad and Tobago which’s inflows increase by 121.6 per cent. For Commonwealth Pacific SIDS, Samoa was the worst afflicted registering a drop of negative 296 per cent to its FDI inflows being the only member states in the region to have a negative value (-US$17.6 million), with the Solomon Islands and Fiji also contracting FDI inflows by 63 per cent and 30 per cent respectively. Although Papua New Guinea’s FDI inflows are not as high in value as India, in terms of percentage expansion of inflows the former fared much better than the latter, recording an exceptional increase of almost 300 per cent during 2020 (US$641.5 million), the highest of all Commonwealth member states for which data is available.

COVID-19 and Commonwealth’s Greenfield FDI inflows

Similar to the analysis on net FDI inflows, COVID-19’s impact on intra-Commonwealth greenfield investments were evaluated by comparing the number of greenfield project announcements between 2017 and 2019 to those announced in 2020, however in this case mostly trends during the first wave of the pandemic (Q1-Q2 2020) will be analysed with only some member cases also involving data from the time frame of the second wave (Q3-Q4 of 2020). Overall, evidence suggests a decline in announced projects for all four quarters of 2020, but most notably in Q2 and Q3, and by the end of the year 494 greenfield FDI projects had been announced, a decrease of 251 projects compared to the 2017-2019 average of 745 annual project announcements. Absolute value-wise, 2020 intra-bloc greenfield inflows fell by US$1.6 billion in Q2, US$4.7 billion lower in Q3, and US$2.9 billion lower in Q4 with losses varying by region; inflows to Commonwealth Africa and the Caribbean and Americas fell by 60 per cent and 35 per cent respectively, which plummeted further down 91 per cent and 80 per cent in Q3. During Q3, European member states registered a whopping 93 per cent decline in greenfield FDI, as well as Commonwealth Asia which’s inflows fell by 60 per cent and the Pacific regional members by 47 per cent. By Q4 member states began to see a recovery in greenfield FDI trends as compared to pre-pandemic averages. African members’ inflows only fell by 3 per cent whilst Pacific members saw their inflows boosted up by 55 per cent; however, the regions of Asia (69 per cent decrease), Europe (96 per cent decrease), and the Caribbean and the Americas (24 per cent decrease) continued to face challenges in raising their inflows.

Impact on jobs created via greenfield FDI inflows

Between 2017 and 2019, greenfield project announcements in the Commonwealth generated an average of 509,780 jobs annually; however, due to the onset of the pandemic, the number of jobs created in 2020 decreased by 42 per cent of this average to approximately 297,098 jobs. Of these jobs, intra-Commonwealth greenfield projects from 2017-2019 generated an annual average of 87,959 which was then cut in half to 45,252 in 2020, lowering the intra-Commonwealth share in total jobs produced via announced greenfield FDI from 17.3 per cent from 2017-2019 to 15.2 per cent. Although the adverse effects were felt across all regions, it was relatively worse for developing countries, especially LDCs and small states including SIDS, despite having smaller shares overall.

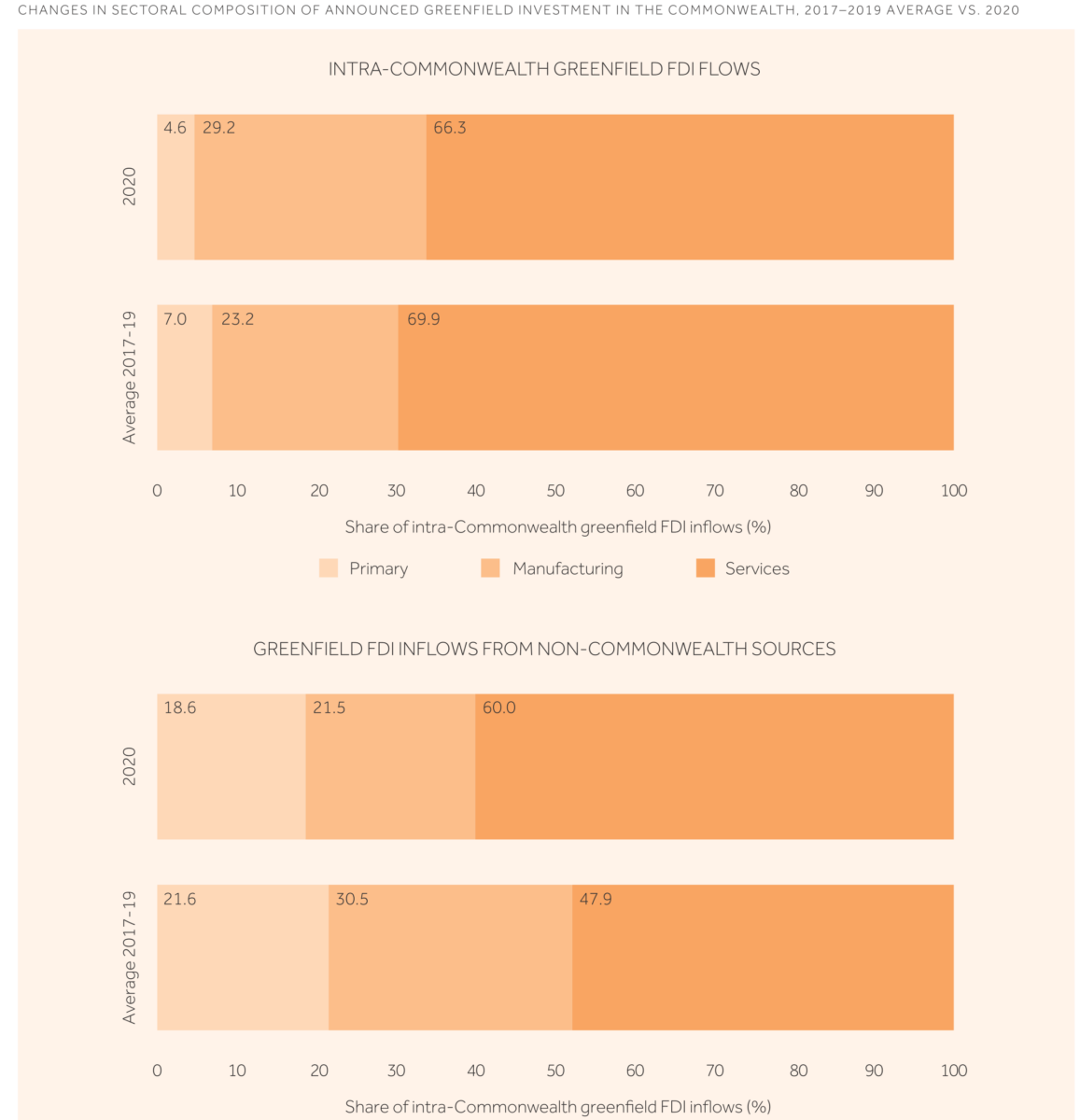

Globally, greenfield FDI flows to the majority of the primary, manufacturing, and services sectors were negatively affected by COVID-19. Compared to pre-pandemic averages (2017-2019), the inflows to the manufacturing sector decreased the most substantially with a 58 per cent drop to US$22.5 billion mainly due to the fall in investments in the metals, food and beverages, and electronic components industries, followed by the primary sector which suffered a 19 per cent drop (US$7.1 billion) due to the decline in investment in coal, oil, and gas. The least affected sector was the services sector, decreasing by 11.5 per cent to US$82.2 billion; although, in terms of value, real estate, tourism, hospitality and financial services were the most affected out of all three sectors’ industries. Intra-Commonwealth greenfield FDI inflows to the primary sector declined by 56 per cent, similar to the sector’s global decline, down from US$2 billion to US$866 million whilst intra-bloc greenfield inflows for the services sector fared worse than the global estimate, plummeting by 34 per cent to US$12.5 billion as compared to pre-pandemic levels. Unlike its global trend, the manufacturing sector’s intra-bloc greenfield investment flows were the most insulated of the three sectors, falling by 11 per cent (US$666 million) as compared to the 2017-2019 average. This was largely due to an investment of US$3.4 billion investment in Malaysia’s chemical industry as well as investment in the member state’s metals and non-automotive transport original equipment manufacturing (OEM) industry, plus sizable inflows into the UK’s pharmaceutical industry.

Impact on sectorial investments

Throughout 2020, only six industries and three services of these three sectors recorded net positive greenfield FDI inflows and remained relatively insulated to the pandemic’s implications on their supply and demand; one industry of the primary sector (minerals industry), three services (warehousing and transportation, ICT, and renewable energy generation) and five industries of the manufacturing sector (business machinery and equipment, chemicals, medical machinery, wood products and non-automotive OEM). The reasons behind their favourable performance, besides these fields being more capital-intensive, are the use of automated machinery and industrial robots, and partially also their placement in Asian GVCs which had already begun to recover in 2020. The relatively better performance of these industries in the manufacturing sector altered the pre-pandemic intra-bloc greenfield FDI structure, increasing the share of inflows for the manufacturing sector by 6 per cent [Figure 5] and whilst the services and primary sectors saw an overall decline in shares they remain sizeable, especially the former that accounts for 66 per cent of the total intra-bloc greenfield inflows.

The impact on the manufacturing, primary, and services sectors across Commonwealth regions largely reflects the Commonwealth’s overall downward trends for FDI investment in these sectors, except for some services in Africa, manufacturing in Asia, and the primary sector in the Caribbean and Americas. As for greenfield investment projects announcements, their trends too largely reflected the bloc’s global greenfield projects’ announcements patterns save for one added primary sector project in Commonwealth Asia and three extra manufacturing sector projects in the Caribbean and Americas member states.

Figure 5: Changes in sectorial composition of announced greenfield investments in the Commonwealth. 2017-2019 average vs 2020

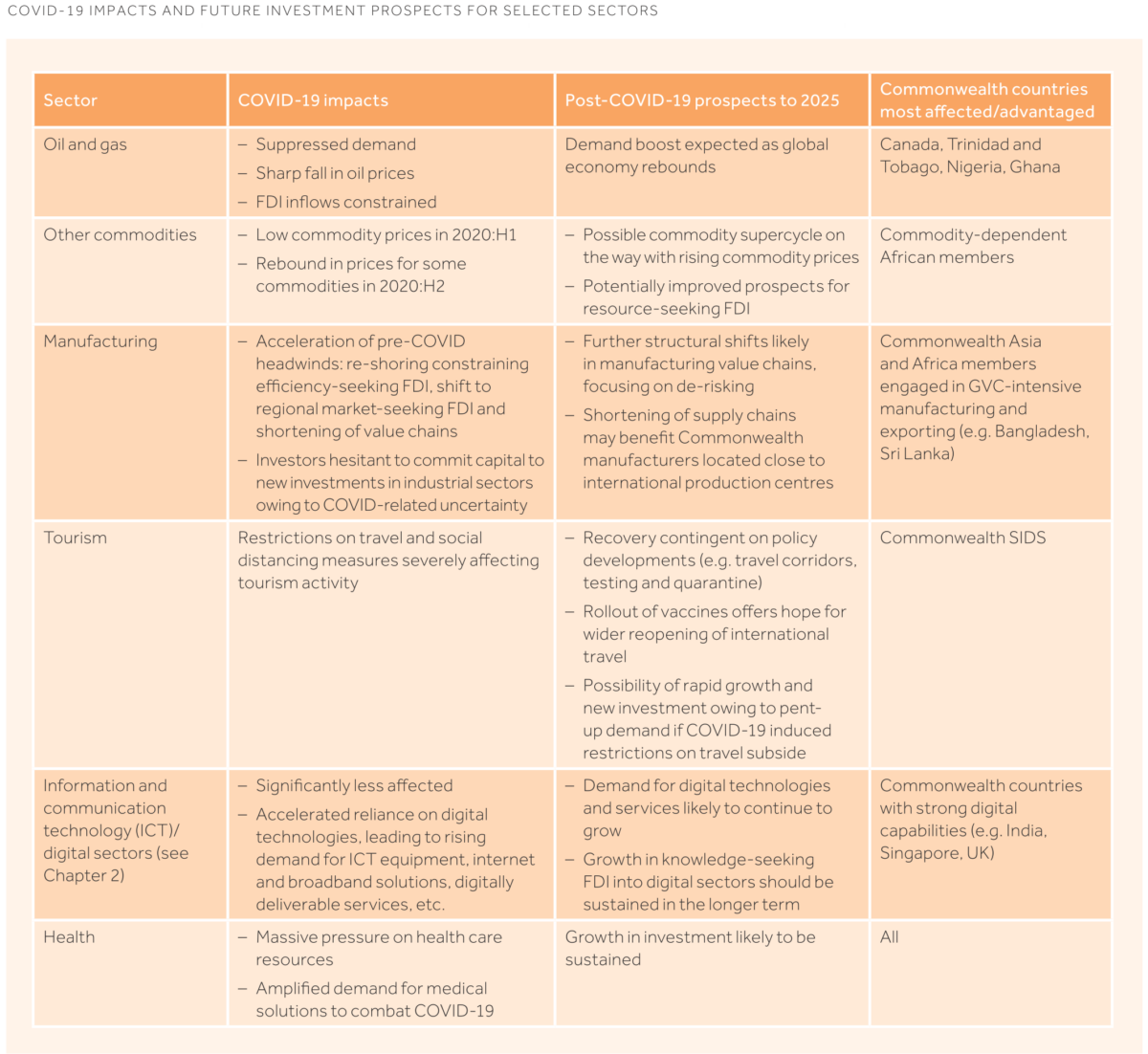

The Commonwealth’s FDI Prospects 2021-2025

As economic and trade recovery remain reliant on the containment and eventual end of the pandemic, the future of FDI investment flows are expected to be diminished and uncertain. Investors remain sceptical and cautious of new capital investment ventures and existing investment projects continue to be postponed without definite restart dates, because of which analysts believe FDI inflows will continue on a downward trajectory at least up until 2022, although the extent of the decline in 2021-2022 will be less severe as compared to 2020. The UNCTAD predicts FDI inflows to recede by 18 per cent in 2021 and then a further 7 per cent in 2022, equalling a cumulative loss of US$220 billion relative to 2019 levels. Fortunately, after this point, FDI inflows are expected to make a U-shape rebound starting in 2023. For Commonwealth member states, the pathway for recovery in FDI inflows will differ widely depending on the resilience of their economic structure, their export volume and trends, as well as their geographical location. According to preliminary assessments, the oil and gas sector will gradually recover as global economic recovery will rebound demand whilst investment in the health and ICT/digital sectors will continue to rise due to consistent demand amidst the pandemic. Overall, the industry-based sectors’ FDI inflows will remain depleted amidst global uncertainty and hesitance of investors, foreboding alarming consequences especially for developing countries that are largely reliant on greenfield FDI and all types of capital investment that is essential for their economic development, upward social mobility, and generation of new jobs. [Figure 6]

Figure 6: COVID-19 and future investment prospects for selected sectors

The after-effects of the pandemic may quite possibly lead to the restructuring of production processes and GVCs, shortening supply chains that may result in re-shoring which would be ideal for Commonwealth member countries in proximity to global production centres, especially Asian and African member states involved in GVC-intensive industries. As such, FDI will be an essential element of this economic recovery and several opportunities to boost FDI have already become evident as the worst effects of the pandemic begin to wane; one such opportunity is Chinese investment. China has been one of the fastest to recover economically from the pandemic’s effects and has been one of the top investors in Commonwealth developing member states of Asia and Africa for the past two decades. Annually between 2017 and 2019, Beijing has invested US$13.7 billion into the Commonwealth countries, becoming a significant source of FDI and commercial loans in transport, energy, telecommunications, and infrastructure projects e.g. industrial parks and special economic zones in Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania. These investments have predominantly arisen from China’s massive transnational investment program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which began in 2013 to promote regional development via integration and infrastructural connectivity. Commonwealth Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific have been extensively involved in the BRI and many member states have benefited positively due to improvements in both hard and soft infrastructure as well as port performance. The component of the BRI that invests in digital economies of BRI member states, the Digital Silk Road (DSR), has been a significant contributor to FDI in Commonwealth countries’ telecommunications sector. Furthermore, China has been a prime contributor to the New Development Bank’s (NDB) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) budget for infrastructural development project loans; while these loans only constituted 5 per cent of global lending by financial institutions in 2020, they have the capacity and capital reserves to increase their infrastructural investment operations. The AIIB, for example, is estimated to have reserves of US$100 billion (half of the World Bank’s reserves) which have been utilised to support countries amidst the pandemic via the Crisis Recovery Facility. Although Chinese FDI into Commonwealth countries, and the world in general, were below average during the first half of 2020, China’s quick recovery indicates that pre-pandemic levels of FDI inflows into recipient countries will recommence soon.

The way forward Commonwealth investments

To ensure the Commonwealth’s policy frameworks currently being developed are engineered to promote sustainable, inclusive, and robust FDI inflow recovery, the Trade Review sheds light on policy recommendations:

1) Due to the upsurge of divestments, rerouting of investments due to shifting geographical criteria for identifying optimal destinations, and diminishing efficiency-seeking investments worldwide, the Commonwealth member states may face heightened difficulty in gathering sufficient FDI inflows for economic recovery. Challenges notwithstanding, if member states make it a priority to strategise investment attraction focusing on market-seeking FDI investors planning to shift away from mainstream destinations to more diverse supply bases (e.g. MNEs are relocating investments outside China due to increased operating costs, supply chain restructuring and the US-China trade conflict’s implications), the Commonwealth states may be able to transform this difficulty into a lucrative opportunity, especially the regions of Asia and Africa due to their low costing markets.

2) For Commonwealth LDCs and developing states to direct domestic savings and FDI inflows towards productive capital, particularly in technologies to improve their current major exports and expand exports to include diversified merchandise and services (such as DDS), these member states must design and advertise innovative and attractive new incentives. They must also enlarge their export capacity for which they must promote foreign investor-friendly trade policies to draw favourable responses. An example of such trade policies includes capitalising on favourable tariff preferences to attract greenfield investments and possibly export tariff-free commodities in developed as well as developing countries, like China, where import tariffs of up to 30 per cent are fairly common.

3) Commonwealth members’ FDI outlooks are dependent on the development of regional trade integration, particularly the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) for Commonwealth Africa, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) for Commonwealth Asia and Pacific states. Between 2010 and 2020, the Commonwealth African members in the AfCFTA represented, on average, 70 per cent of intra-African announced greenfield FDI and 85 per cent in 2020. Prioritising the implementation of the AfCFTA Investment Protocol will produce added investment opportunities and inflows for these African member states. Furthermore, negotiations are currently taking place within the AfCFTA to design a framework to deepen the commitment of members to intra-African investment flows, while simultaneously creating a platform for members and third parties to discuss investment facilitation and investor obligations. These negotiations must be expedited as this will facilitate clarity between African states and foreign parties, ensure investment protection for both sides, and reduce investment transaction costs.

The RCEP, being one of the most sizeable free trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific, of which the Commonwealth states of Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Singapore are a part, is a lucrative opportunity to enhance investment flows and serves as a guarantee for the region’s investors of the RCEP’s members’ obligation to integrate and liberalise the region’s rules-based investment projects.

4) Commonwealth member states must give utmost priority to capitalising on the “Commonwealth Advantage” (discussed in section 3.1) which, although already a key contributor to total Commonwealth FDI inflows, has potential to contribute an even larger share to overall inflows and play a crucial part in the revitalising the Commonwealth and reversing the adverse impact of the pandemic. In addition, the Commonwealth possesses a dynamic diasporan community that may become significant investors for the Commonwealth. For instance, a survey of professionals and businessmen in diaspora communities in the UK from six Commonwealth countries (Bangladesh, Fiji, Ghana, Jamaica, Kenya, and Nigeria) revealed that over 60 per cent of these individuals expressed willingness to invest in Commonwealth countries with which they feel a connection. Further studies reveal that diaspora professionals are majorly entrepreneurial and actively seek to invest via starting new businesses. As such, to maximise their potential, these individuals may be provided with opportunities to invest via investment platforms for crowdfunding and bonds, and may also be encouraged to connect with innovators and other investors to establish a strong foundation to mobilise their savings and inject FDI into the Commonwealth nations they reside in. Diaspora investments are known to be more beneficial than other FDI as these inflows tend to be more stable, create more local employment, and have above-average spill-over effects.

5) Recent discussions by some members of the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative emphasised the need to streamline and accelerate administrative procedures, domestic and transborder cooperation, and temporary entry facilities for investors and businesspersons to rekindle global FDI projects. The WTO plans to implement multilateral rules and regulations for formal negotiations for multilateral investment facilitation which, if implemented, may result in added inflows into the Commonwealth member states. While this initiative is promising, it must be kept in mind that the question of the efficacy of global multilateral trade remains unclear, especially in the wake of debates for near-shoring and reconfiguration of supply chains. Furthermore, there is broad consensus that the WTO still requires further reforms to maintain its credibility as an organisation effective in tackling global trade issues and promoting multilateralism.