Commonwealth Trade and Digitalisation

Commonwealth Trade and Digitalisation

Pre-Pandemic Commonwealth Digital Trade

Commonwealth trade and digital goods

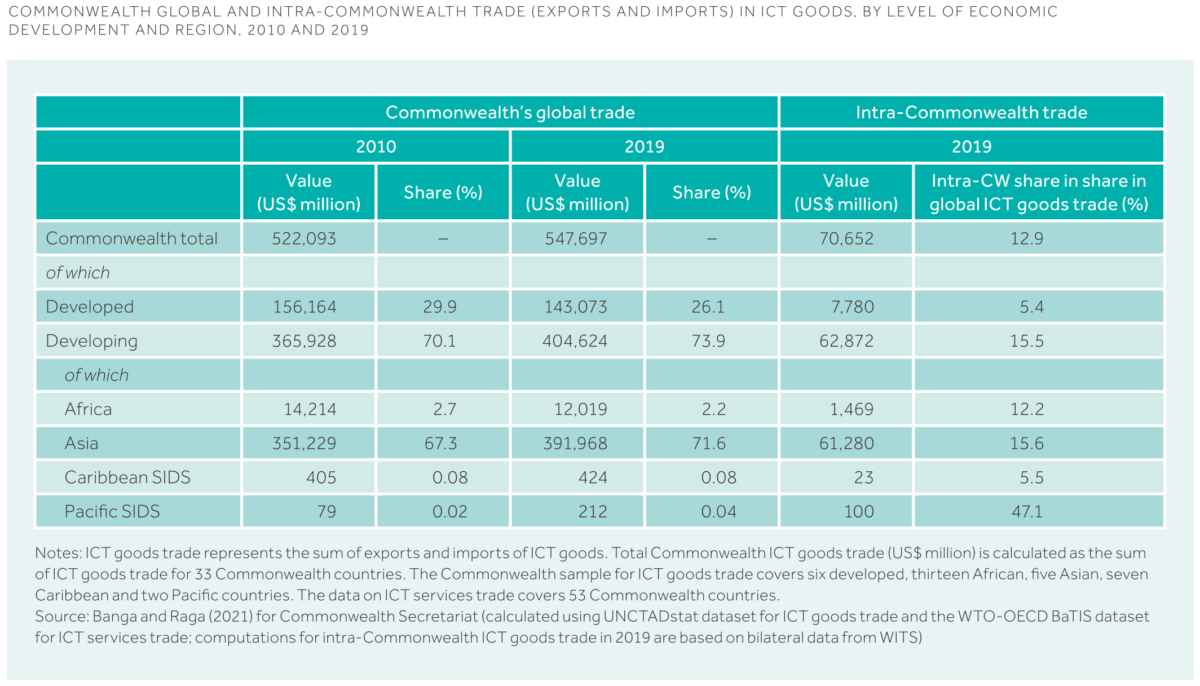

The Commonwealth’s share in global ICT goods fell from 14.5 per cent in 2010 to 11.7 per cent in 2019 albeit in absolute value terms it increased from US$522.1 billion to US$547.7 billion. Half of the ICT goods trade was in intermediate components for electronics (valves, tubes and electrical apparatus etc.) followed by computers and their auxiliary equipment (21.8 per cent) and communication devices (18.8 per cent). The Commonwealth’s ICT goods share predominantly comes from a handful of member states namely the UK, Canada and Australia from the developed countries category and Singapore, Malaysia and India from the developing countries category that collectively constituted 96 per cent of the ICT goods from 2010 to 2019. Regionally, Commonwealth Asia has been the main provider of Commonwealth ICT goods trade since 2010, providing a share of 71.6 per cent in 2019. Within the region, Singapore and Malaysia are the predominant sources for ICT goods, making up 57 and 32 per cent of the share between 2010 and 2019.

As for the developed states of the Commonwealth, the six countries all together constituted 26.1 per cent of the ICT goods trade in 2019 although they have been in decline share-wise since the beginning of the decade when their share was at 30 per cent. Commonwealth Africa’s ICT goods trade has also been declining since 2010, having dropped its share from 2.7 in 2010 to 2.2 per cent in 2019 which was mainly due to the decline of ICT imports and exports of South Africa which is the region’s main supplier (70 per cent). Shares of the Caribbean and Pacific SIDS in 2019, 0.08 and 0.04 respectively, have remained minor since 2010. Intra-Commonwealth trade of ICT goods was pegged at US$70.7 billion for 2019 which is equivalent to 13 per cent of the member countries’ global ICT goods trade which is a lower share compared to the intra-Commonwealth share of the bloc’s total goods trade (15.6 per cent).

Figure 1: Commowealth global and intra-commonwealth trade (exports and imports) in ICT goods, by level of economic development and region, 2010 and 2019

Commonwealth trade in digitsable goods

Besides ICT goods, digitsable products, meaning any product that is electronically transmittable like audio and video files, video games, e-books etc., are also significant contributors to the Commonwealth’s digital goods trade. These products are burgeoning in value and quantity due to innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data analysis, and the internet of things (IoT) that are reducing the cost and time taken for the cross-border trade of these items. Intra-Commonwealth trade of these digitsable products (including both exports and imports) amounted to US$4.6 billion in 2019; from 2017-2019 the UK, Singapore, Australia, Malaysia and India were the major exporters and importers but South Africa was the top importing country, taking almost one-third of the entire intra-Commonwealth trade in digitsable goods. Other Commonwealth African countries are gradually increasing the production of such digitsable content as well; Nigeria’s Nollywood has now become an established industry gaining 89.6 per cent of its US$3 billion income online, ranking third internationally after Hollywood and Bollywood and becoming the second-largest source of the country’s employment after the agriculture sector. As the African region’s internet connectivity improves and the citizens consume more digital content, entertainment start-ups funding has surged from 0.15 per cent of the national fund in 2019 to 2 per cent in 2020; however, the high data costs and consequently piracy may jeopardize the sustainability, in terms of revenue and employment of the industry.

Commonwealth trade in digital services

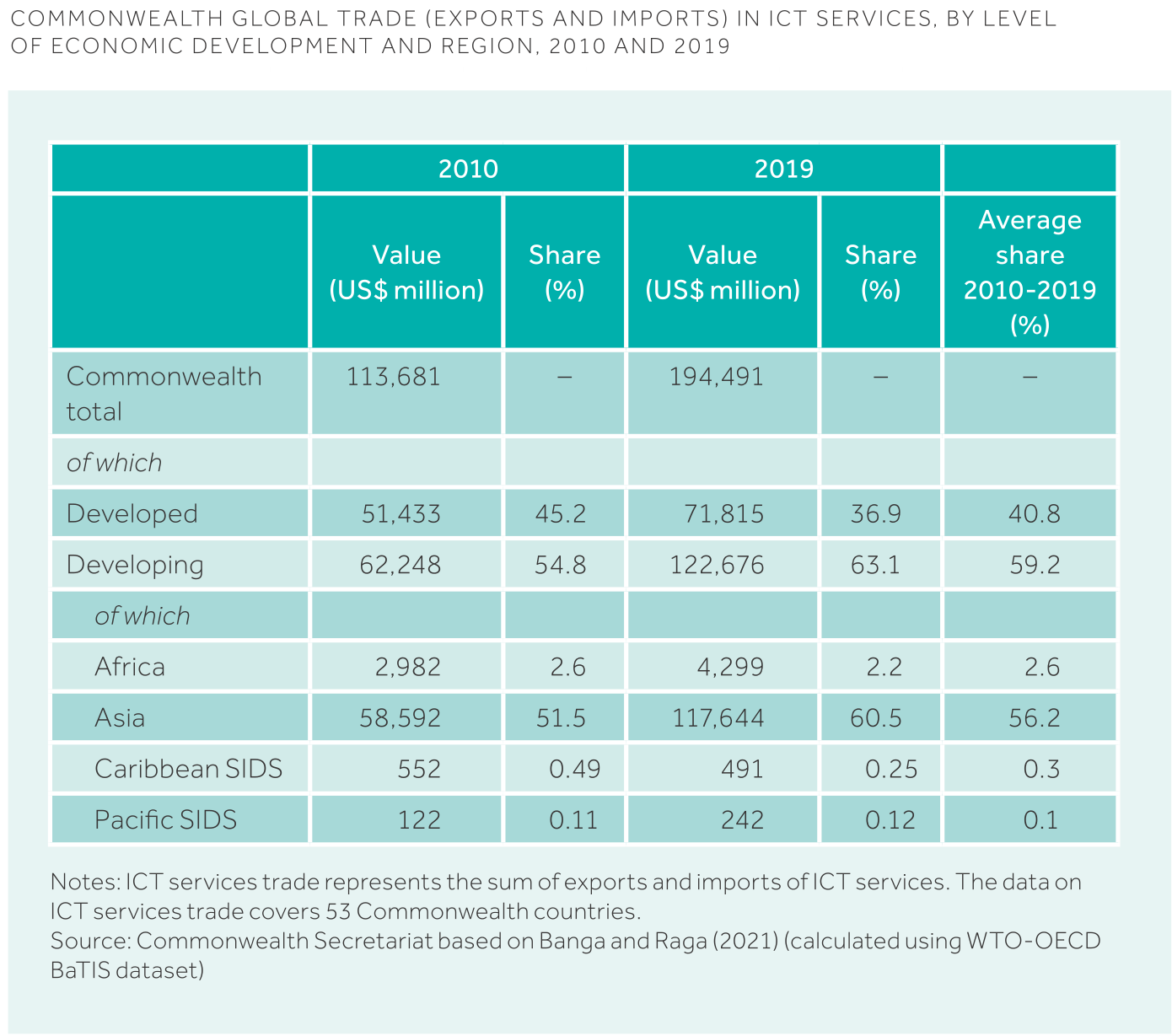

ICT services constitute a larger share of Commonwealth trade than ICT goods, expanding in value from US$113.7 billion in 2010 to US$194.5 billion in 2019 making it a sizable share of member states’ GDP in services. However, in terms of the Commonwealth’s share of ICT services globally, there has been a 3 per cent decline since 2010 meaning that right before the pandemic the Commonwealth’s global share of ICT services was estimated to be 18.1 per cent. Two-thirds of the Commonwealth’s ICT services in 2019 came from the developing members, an 8 per cent increase since 2010.

Figure 2. Commonwealth global trade (exports and imports) in ICT services, by level of economic development and region

Regionally, Asian countries represented 60.5 per cent of the total share in 2019, an increase of 9 per cent since 2010; the two leading contributors in the region were Singapore and India. Commonwealth Africa’s share of ICT services is identical to its share of ICT goods (2.2 per cent) which have also declined in number since 2010. The Caribbean and Pacific SIDS’ shares of ICT services have declined over the decade, making up less than 1 per cent combined, but are greater than their shares of ICT goods. Small states also have a minimal share in ICT services that have also been declining throughout the decade. ICT services exporting members are especially reliant on intra-Commonwealth trade; according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-WTO Balanced Trade in Services (BaTIS) dataset, 21.8 per cent of the Commonwealth’s ICT services are exported to other member states, an average even higher than that of the Commonwealth’s total exports that stand at 20.1 per cent. From 2017-2019, 22 per cent of the Commonwealth countries exported more than one-fourth of their ICT services to other member states; New Zealand, Brunei Darussalam and Cameroon exported more than half, and Australia, Bangladesh and Malaysia exported more than one-third. These exports in value, however, remain undiversified with 90 per cent of the total ICT services exports coming from just six countries- the UK, India, Singapore, Australia, Malaysia, and Canada. This trade review asserts that the previously discussed concept of the “Commonwealth Advantage” may be an important facilitator for the intra-Commonwealth cross-border operations of these ICT services.

Trans-border data and information processing is a critical aspect of all types of digital trade and is obscuring the difference between what constitutes a digital product and a digital service. For example, the software-as-a-service (SaaS) and platform-as-a-service (PaaS) are IT infrastructure services that facilitate both traditional and digital goods as well as services trade; while SaaS enables applications that drive the sales of goods, PaaS helps deliver e-commerce purchases and virtual services. Furthermore, an increasing number of products have digital content or services incorporated into them such as smart TVs and refrigerators. Digital trade is part of a larger digital ecosystem that includes the electronic infrastructure of computers, mobile devices, cyber intermediation platforms, e-commerce and much more, which is why digital trade is prevalent across more sectors than just the ICT trade sector. Due to the immensity of this ecosystem, there is a need to guarantee integration of operations across the different and constantly developing digital dimensions and also provide a comprehensive regulatory framework to streamline international automated trade that is insulated from vulnerabilities to cyber-attacks and data breaches. Commonwealth policy-makers and decision-making bodies must face the challenge of governing taxation, payment systems, trans-national data processing, cybersecurity, dispute resolution, and market concentration and competition of digitally traded goods and services.

Commonwealth trade in digitally deliverable services

ICT services are necessary facilitators for digitally deliverable services (DDS) via SaaS or ICT-enabled operations in legal or financial services as well as education, vocational training, marketing, health care, management, and other such business and/or private use oriented services. Commonwealth DDS trade, both in terms of value and share of Commonwealth’s total services trade, has been on an upward trend since 54 per cent of the Commonwealth’s services trade has been delivered digitally; in 2011 the value of these services was an estimated US$815 billion which has increased by 44.8 per cent to US$1.2 trillion in 2019. However, reflecting the same pattern as Commonwealth’s global services exports, the DDS export shares are saturated in a few member countries. In 2011, 62 per cent (US$506 billion) of DDS exports came from developed members but during the decade, these shares have declined to 55.6% (US$656 billion) owing to the 6 per cent increase to 40.9 (US$278 billion to US$482 billion) per cent share of Commonwealth Asia driven by Singapore and India. Commonwealth Africa’s DDS share has remained constant at 3.1 per cent throughout the decade whereas for Caribbean and Pacific SIDS the share has decreased from 0.4 and 0.2 per cent to 0.3 and 0.1 per cent respectively. Similarly, eight LDCs of the Commonwealth for which DDS services data was available, namely Bangladesh, The Gambia, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Solomon Islands, Uganda and Zambia, recorded a more than doubled increase in DDS value from US$3.6 billion in 2011 to US$7.7 billion in 2019 but shares wise theirs declined from 1 to 0.7 per cent. Yet this does not negate the potential of small states, LDCs and SIDS to increase their DDS shares, as it may be the best solution to tackle the challenges they face in trade development due to the lack of physical infrastructure and capital investments. Furthermore, DDS trade can be an answer to the obstacle of geographical isolation from mainstream shipping lines that these member states face because capitalising on cyber trade will allow them to deliver services remotely to large markets at lower costs. Looking at the top ten providers of DDS services, the top 5 countries- United Kingdom (estimated US$440.9 billion), Singapore (US$209.7 billion), India (US$200.4 billion), Canada (US$100 billion), and Australia (US$ 33 billion) account for 82 per cent of DDS trade, while the rest is made up mainly by the remainder of the Top 10- Malaysia, Malta, Nigeria, Ghana, and Cyprus. Upon closer inspection of this ranking, a key fact to be noted is that these countries have a larger value and share of DDS due to their massive populations; larger population sizes mean more providers and consumers of DDS reside in these states. Based on this, a review of DDS trade per 1000 people (between 2017 and 2019) revealed the top 10 DDS providers also included small states and Caribbean SIDS- Antigua and Barbuda, St Kitts and Nevis, and The Bahamas, while Grenada, Dominica, and Saint Lucia ranked just outside this list but still in the top twenty. Therefore, the potential advancement of DDS in these countries and the benefits to their trade development can not be overstated.

E-commerce in the Commonwealth

E-commerce is defined as the trade of goods and services using online platforms created solely for collecting or placing orders for all types of transactions e.g Business-to-Business, Business-to-Customer, Consumer-to-Consumer etc. Data collected for pre-pandemic e-commerce activity demonstrates uneven levels of e-commerce activity across the Commonwealth. The UNCTAD Business-to-Consumer (B2C) E-Commerce Index, is a scale of 152 countries that measures the readiness of states to support B2C transactions online (note: not all types of e-commerce) via four indicators:

1) Population’s (above the age of 15) ownership of an account for online/mobile money providing services

2) Percentage of population using the internet

3) The Postal Reliability Index

4) Security of internet servers (per 1 million people)

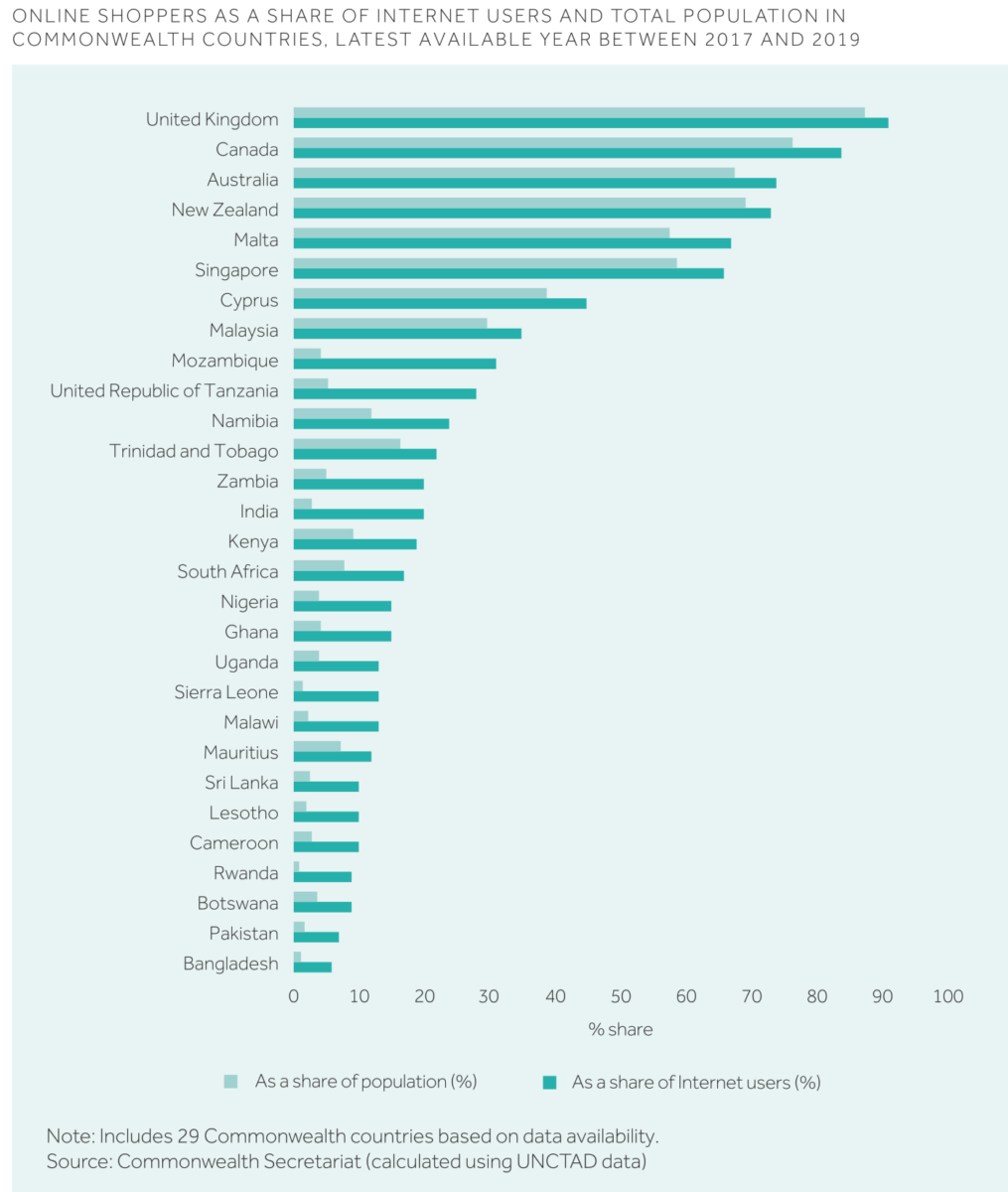

Twelve Commonwealth members were above global average values on the B2C E-Commerce Index in 2020, six of which were the developed economies that were amongst the top 20 countries on the index, while the remaining six were developing economies- Singapore, Malaysia Mauritius, India, South Africa and Jamaica. However, several African and Asian Commonwealth states (mostly LDCs) were found to be on the bottom half of the Index; furthermore, the performance of the Commonwealth countries in 2020 worsened in comparison to 2019 wherein 22 Commonwealth states beat global averages. There is further disparity amongst the Commonwealth states’ population of internet users in terms of their online shopping participation; for the 29 members for which data on online shopping usage was found, 19 countries have less than 10 per cent of their population using the internet (besides Namibia and Trinidad and Tobago) of which one-fourth shopped online. In Rwanda, Botswana, Pakistan and Bangladesh less than 10 per cent of internet users shop online, representing less than 2 per cent of the population in the cases of Pakistan and Bangladesh. Due to their well-equipped digital infrastructure and a higher percentage of online shopping platforms, developed countries are the category of member states that have above-average shares (at least 40 per cent and above) with the UK being at the top with 90 per cent of internet users (87 per cent of the population) participating in online shopping. As of 2019, Malaysia is the only developing country in the Commonwealth that is a top performer in B2C e-commerce sales which made up 6 per cent of its GDP in 2017; this highlights a key area of digital trade that has immense growth potential therefore the developing members are strongly recommended to promote an empowering environment for e-commerce.

Figure 3. Online shoppers as a share of internet users and total population in Commonwealth countries, latest available year between 2017 and 2019

Investment in the Commonwealth’s digital sectors

According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), investment in Commonwealth countries’ telecommunication services, a vital aspect of digitisation, has increased by 24 per cent from 2010 to US$50.6 billion annually in 2017 increasing the cumulative investment amount since the start of the decade to US$ 355.6 billion. Large portions of this investment went into India (US$106.1 billion or 29.8 per cent), Canada (US$78.1 billion or 21.9 per cent), Australia (US$62.9 billion or 17.6 per cent), Malaysia (US$18.9 billion or 5 per cent), and Nigeria (US$13.8 billion or 3.8 per cent). Sizeable investments also went to LDC members Bangladesh (US$8.8 billion or 2.5 per cent), Zambia (US$2.3 billion or 0.6 per cent), and Rwanda (US$630.6 million or 0.18 per cent).

Greenfield investments in Commonwealth digital trade

The rise in investment levels is mainly driven by greenfield foreign direct investment (FDI) in the communications and IT and software services sectors with US$12.3 billion and US$12.6 billion worth of capital investments announced in projects for 2019, respectively. For the communications sector, greenfield FDI inflows were mostly directed into developed economies and the developing countries of Commonwealth Asia and the sector fared well relative to other sectors as it was the most insulated against the economic shocks caused by the pandemic, showcasing the importance of such technologies in maintaining trade activity during the peak of COVID-19. In 2020, overall investment in the communications sector rose by 50 per cent (relative to 2019 levels) due to the expansion of such services in Commonwealth Asia and Africa, including LDCs; however, intra-Commonwealth greenfield investment in this sector has been unstable.

Intra-bloc greenfield FDI in the IT and software services sector has more than doubled since 2010 reaching an estimated amount of US$2.2 billion in 2019; in terms of the share of this sector in the overall greenfield FDI into Commonwealth, the percentage increased from 1.5 per cent to 8 per cent. Increase in inflows notwithstanding, 85 per cent of these greenfield FDI flows have remained saturated in just 5 member states- Australia, Singapore, the UK, India and Canada while substantial portions of the remaining 15 per cent were allocated to South Africa, Nigeria, Malaysia, and Rwanda, the last of which is an LDC wherein the government prioritised digital economy development and received US$47 billion in intra-bloc greenfield FDI. While the UK, Canada and India were among the largest recipients, they were also the largest distributors of greenfield FDI with nearly 75 per cent of intra-Commonwealth greenfield investment flows coming from the UK, India, and Canada. Global greenfield FDI into the IT and software services sector in developing member states declined by 22 per cent in 2020 diminishing the growth rate to just 3.2 per cent, showcasing that the sector was not as resilient as its communications services counterpart. Fortunately, overall investment in digital sectors of the Commonwealth remains on an upward trend, in the case of India for example record numbers of new mergers and acquisition agreements have been signed since late-2020, and with the accelerated expansion of digital technologies undertaken due to the pandemic, these sectors are likely to sustain FDI inflows in the long term.

Digital trade during COVID-19

COVID-19 has sped up the already growing digitalisation of global economies as all forms of businesses shifted their activities to online platforms. In 2020, the internet user community increased by 7.3 per cent (316 million) though this number is surely higher as some data has been lost due to difficulty in accurate reporting during the pandemic. Global internet usage stands at 51.8 per cent and although the percentage of the Commonwealth’s internet users has doubled to 48 per cent in the past decade some states, especially LDCs and SSAs, are behind the global average in ICT adoption and with the sudden shift of global trade to digital platforms, they are at risk of an even wider digital development gap that may hinder economic recovery. In the past few years, technological advancements and innovative electronic platforms have expanded international trade of a variety of digital, digitally deliverable, and digitally purchased goods and services. Online purchasing, which encompasses e-commerce, has become a leading platform for the trade of traditional goods and services.

The pandemic has been both an obstacle and an accelerator for Commonwealth digital economy development. On the one hand, it has been detrimental to the digital goods and services demand and supply chains; for instance on the supply side, labour-intensive ICT goods manufacturing with minimal automation has been disrupted due to a dearth of labourers, raw materials and intermediate inputs when lockdowns, social distancing rules, and border restrictions were implemented. Disruptions to the agricultural and manufacturing sectors have adversely affected product supply in e-commerce value chains while logistical delays in transportation have brought down transnational e-commerce deliveries. Simultaneously, digitisation of trade via e-commerce has been a crucial no-contact alternative for the trade of merchandise and services causing a surge in online demands. To showcase a few examples, an African e-marketplace platform of Nigerian origin called ‘Jumia’ increased its sales by 50 per cent in the first two quarters of 2020, in Kenya e-commerce usage tripled throughout the same year, and in the UK the share of e-commerce in total retail sales rose 31 per cent in the first half of 2020. Furthermore, a framework developed by Banga and te Velde (2020) analysed the effects of COVID-19 on the digital economy of 23 countries mainly LDCs in Africa and the Asia-Pacific region and discovered a correlation between firms’ digitisation of business activity (using digital infrastructure, ICT and e-commerce) and increase in exports compared to previous-year levels. UNCTAD studies also confirm that consumer consumption has shifted to online shopping for necessities such as medicine, groceries, hygiene products etc. Besides the surge in online purchasing and e-commerce, the significant amount of the world population switching to work-from-home has caused a significant spike in the purchasing of digital consumer products such as computers, laptops and tablets. In 2020, the world purchased 13.1 per cent more personal computers than pre-pandemic averages; the UK’s imports of laptops rose by 20 per cent between March and October of the same year. Digital communications equipment and services facilitating internet access increased proportionally to the increase in digital consumer product usage. Heightened digital product usage couples with travelling restrictions and cancellation/postponement of public activities led to increased demand for DDS and creative content such as audio/video streaming, e-books, music and games which ensured the livelihood of many content creators and artists.

India’s ICT services exports and the pandemic

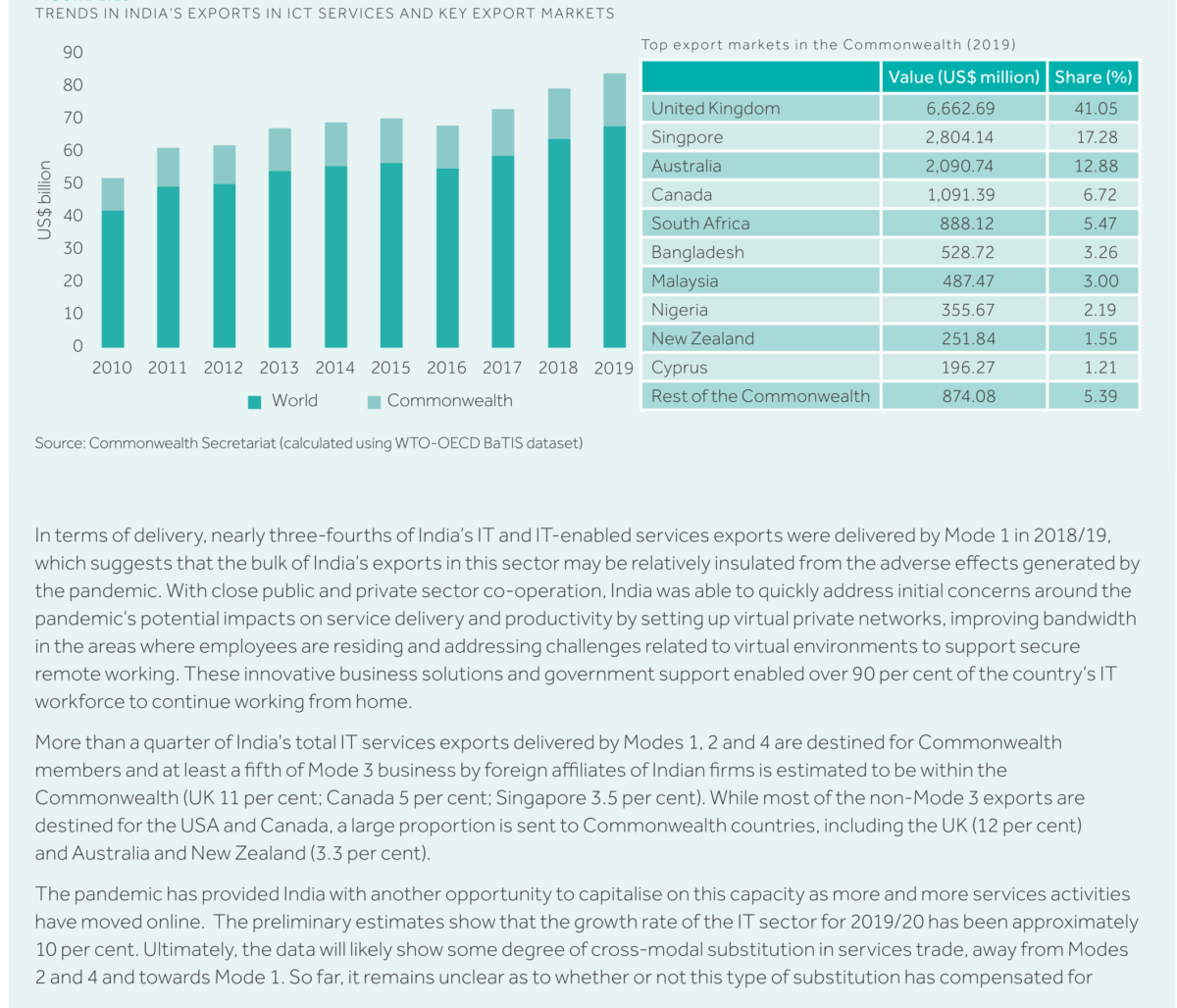

In the case of India, the largest supplier of ICT and related services in the Commonwealth (second globally after Ireland), these digital services accounted for one-third of its total services exports (US$70 billion out of US$215 billion) in 2019 even before the pandemic began. One-fourth of these services were consumed within the Commonwealth, showcasing the increasing share of India’s ICT services being directed towards the bloc which has doubled in terms of value from US$9 billion in 2010 to US$17 billion in 2019. [Figure 4]

Figure 4. Trends in India’s exports in ICT services and key export markets

Global services trade, as mentioned in Chapter 1, shifted global the usage of modes of supply mainly to Mode 1, involving transnational supply of trade via online and digital means. Nearly 75 per cent of all Indian IT and related services in 2019 and earlier were delivered via Mode 1 which explains why India’s digital economy was the most insulated against the shocks of COVID-19 and with close coordination between the private and public sectors the government was able to establish private virtual networks and improve internet bandwidth and security of private servers in commercial areas. These swift policy revisions eased the shift of 90 per cent of the workforce involved in IT and related services due to which the Indian IT sector grow by an estimated 10 per cent between 2019 and 2020 and according to The Reserve Bank of India the country’s monthly services exports since April 2017 were consistently at a value of US$17 billion, just US$1 billion short of pre-pandemic values.

Digitisation of the economy has undoubtedly showcased its crucial role in mitigating COVID-19 shocks and facilitating trade without jeopardizing the health of the world population; however, digitisation is not globally uniform, and the gap in the digitisation rates between countries could be extremely damaging to the lesser equipped countries, who may not only not recover as fast as their technological advanced counterparts. While it is true that the supply of services via Mode 1 is the optimal solution for service trade during the pandemic, it must be clarified that switching to Mode 1 requires advanced digital infrastructure and connectivity, skilled human capital, and sufficient server capacity; this is the biggest challenge for Commonwealth states as the level of preparedness amongst the bloc is extremely uneven. In addition, although the use of such digital alternatives is leading to the discovery of new and innovative opportunities in technological advancement that may be pivotal for post-pandemic global economic recovery, this brings about several new risks to consumer protection and creates new avenues for illegal trade i.e. smuggling of illegal drugs, trafficking, counterfeit medicine, knock-off protective equipment and toys which are especially worrisome in the Southeast Asian markets.

Expansion of Commonwealth internet and ICT usage

It has become evident by the data presented in this chapter that inflows of digital goods and services are predominantly sourced from a handful of leading developed and developing countries, leaving behind LDCs and most small state members of the Commonwealth due to which they have been unable to fully capitalise on the benefits of digitisation. The uneven distribution of capability, skills and readiness for digital trade is a problem not only across different Commonwealth states but also between men and women, especially for internet usage.

Despite the increasing use of mobile internet, internet access and usage across the Commonwealth is quite dissimilar; in 2019, the share of the population using the internet in the developing countries overall was 89 per cent, in the Caribbean SIDS it was 62 per cent, and in Commonwealth Asia, it was 54 per cent, all of which were above the global average of 51 per cent. However, the SSA and Pacific SIDS remained below the world average, both at around 32 per cent. Fortunately, despite their current lag, these regions are increasing their internet usage at a fast pace. For example, African members have seen their internet use triple from 11 per cent in 2010 to 32 per cent in 2019, and overall the Commonwealth’s internet usage has increased almost two-fold from 27 per cent in 2010 to 48 per cent in 2019. To keep this accelerated pace, investment in expanding broadband access for SSA and LDCs must be made a top priority. Besides investment, it is also crucial for Commonwealth members’ governance and policymakers to understand the components required for increased internet usage which include affordable broadband and ICT hardware and services, robust digital infrastructure, fast and secure servers and regulation of telecommunications and e-platforms. Affordability is key for digitisation in the Commonwealth. For example, in terms of the gross national income (GNI) per person, the monthly cost of 1.5 GB of mobile bandwidth is only 0.66 per cent of GNI for developed member states whereas for LDC’s it is more than ten times higher at 9.30 per cent, more than triple of the Commonwealth average of 4.26 per cent. High import tariffs on hardware and broadband network equipment are another aspect that has been hindering the growth of member states’ digital economy; for the Commonwealth developed countries the tariffs are on average at 1 per cent, whereas for developing countries and LDCs it is at 8 per cent, and the overall Commonwealth tariff average for such goods at 7.50 per cent, 1.1 per cent higher than the global average. 11 Commonwealth states that belong to the WTO’s Information Technology Agreement (ITA) are the exception to the previously mentioned tariffs for IT products. Internet accessibility and affordability are hampered by heavy tariffs on internet devices as high costs on mobile phones and laptops discourage internet usage. In Africa, 60 per cent of internet users connect to the web via their mobile phones however the price for the handheld devices ranges from US$35-45 which is equivalent to almost 80 per cent of the salary for some African countries which is why it is pertinent to lower import tariffs, facilitate local manufacturing and create more structured payment plans to enhance ICT accessibility and lower costs.

Research indicates a relation between internet connectivity speeds and GDP plus productivity. In developing member states heightened internet demand due to COVID-19 restrictions reduced broadband speeds by 20-30 per cent causing notable differences in the download speeds of developing members compared to developed members such as Singapore, New Zealand and Canada that had download speeds of 50 Mbps and above whilst Tanzania, Mozambique, Bangladesh and Pakistan had download speeds peaking at only 5 Mbps. Service providers of both developed and developing member countries responded by cancelling data limits or granting additional gigabits free of cost, boosting capacity, and lowering mobile transaction costs and governments in turn provided these operators with additional spectrum. The pandemic has accelerated private sector initiatives for bolstering and improving internet infrastructure in LDCs and developing member states such as satellite broadband, better mobile web services via high-altitude balloons, and Google’s undersea cable network Equiano that will in the first phase connect Portugal and South Africa while establishing its first branch in Nigeria and is expected to greatly enhance the bandwidth of the region’s internet. The Digital Silk Road (DSR), an element of China’s Belt and Road Initiative that pertains to the virtual and digital limb of the transnational infrastructure and investment program, is an exceptional opportunity for developing members that wish to enhance their digital infrastructure. Member states can bring in Chinese investment via the DSR in various fields ranging from telecommunication networks, artificial intelligence and cloud computing to mobile payment systems, e-commerce platforms and smart cities. While the DSR is a lucrative source of investment, it is advised that the Commonwealth states remain cautious of security-related concerns; some member states like Australia have already banned Chinese firms from 5G infrastructure projects.

Internet Access across the Commonwealth: What makes top performers different?

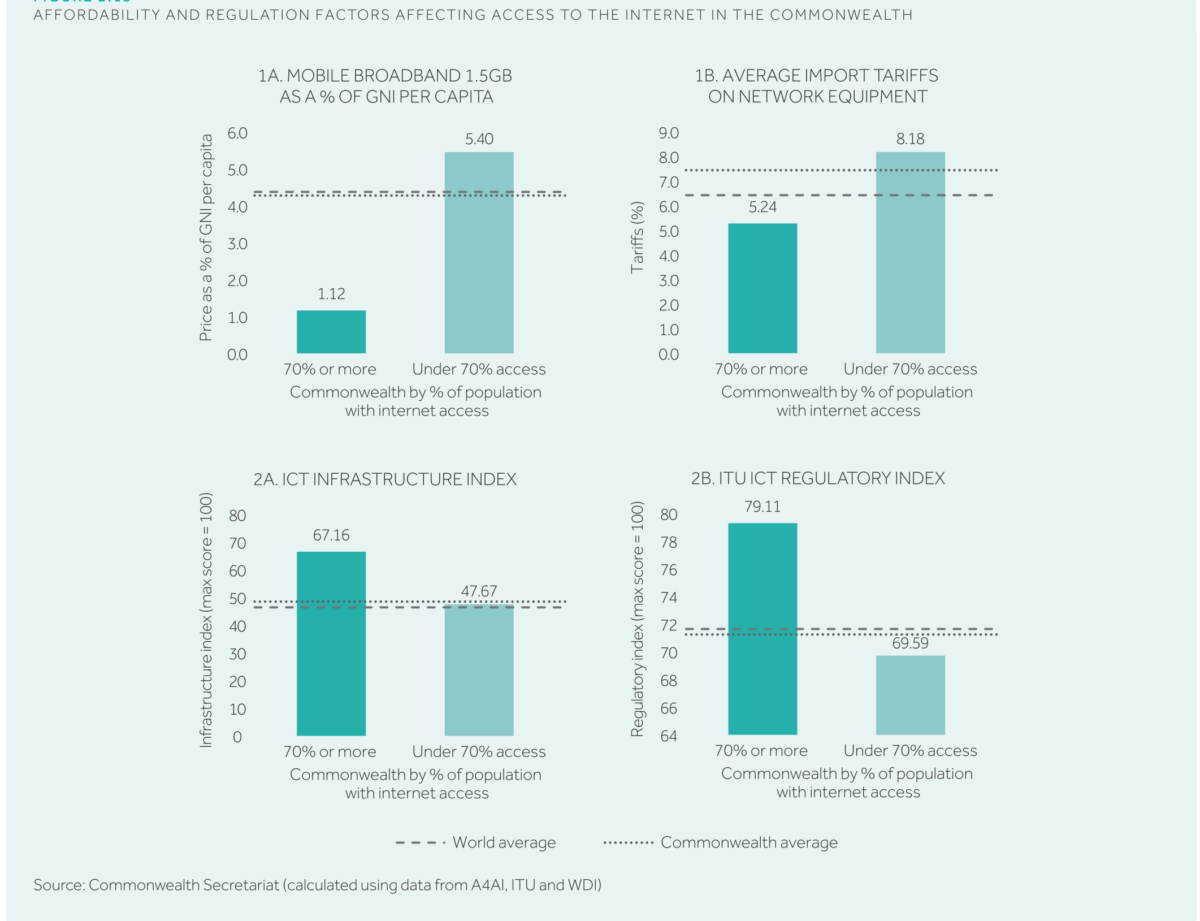

To showcase several likely factors for higher access to the digital economy, a comparative case study was conducted between 14 Commonwealth countries with more than 70 per cent of the population using the internet and 40 member states with lower access. Results showcased two main factors:

1) Affordability: An accurate measurement of affordability is the monthly cost of 1.5 GB worth of mobile bandwidth using per-person GNI [Figure 5]; the optimal GNI percentage target for entry-level fixed and mobile broadband was set at 2 per cent by the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development in 2018 that only 17 member states managed to achieve in 2019. The Commonwealth average GNI used per 1.5 GB of mobile bandwidth was 2.2 per cent; for member states with more than 70 per cent of the population using the internet, the cost per capita was found to be 1.12 per cent which is five times cheaper than the 5.40 per cent required by member states with less than 70 per cent of the population using the internet. For LDCs, the cost is even higher pegged at 9.3 per cent, but the highest percentage requirement was recorded at 16 per cent in Malawi, Sierra Leone and the Solomon Islands.

Figure 5. Affordability and Regulation Factors affecting access to the internet in the Commonwealth

The second factor on which affordability of the internet is dependent is the import tariffs on ICT hardware and networking equipment. The Commonwealth average is 7.5 per cent although across members the range is quite wide as the import tariffs in The Bahamas go up to a whopping 35 per cent whilst 7 Commonwealth states, including 4 SIDS, have zero tariffs. The average for those members with less than 70% of the population using the internet is 8.5 per cent.

2) Regulations: Strict and efficient regulatory practices are crucial for the development of ICTs leads to better affordability and access across the population. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) ICT Regulatory Tracker, which is based on four main components-regulatory authority, regulatory mandates, regulatory regime and competition framework for the ICT framework, is used to assess the efficiency and robustness of ICT regulations. According to this tracker, the Commonwealth average is a score of 72.06 out of 100, while the score of those member states with greater than 70% citizens using the internet is 80. For Commonwealth LDCs the score is a low 68, although this too is varied as countries such as Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda score above 80 while Sierra Leone scored 56. The ICT Infrastructure Index calculated by the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) evaluates the performance of policy frameworks in encouraging infrastructure expansion and the extent to which satisfactory ICT infrastructure has been implemented. As of September 2020, 51 member states, except for Dominica, St Kitts and Nevis, and Tuvalu, have registered national broadband plans and the communication index score for those states with more than 70% of the population accessing the internet is 67 whilst those with less access scored an average 44. The majority of Commonwealth LDCs, save for Rwanda, ranked even lower showcasing the need for more investments and prioritisation of ICT infrastructure.