Reigniting Old Flames: The Liberalisation of Trade in Environmental Goods and Services (EGS)

Reigniting Old Flames: The Liberalisation of Trade in Environmental Goods and Services (EGS)

Commonwealth Secretariat International Working Paper 2022/02

On 8 June 2022, the Commonwealth Secretariat (hereby referred to as ‘the Secretariat’) published a study jointly conducted by the Secretariat’s Economic Adviser on Multilateral Trade, Collin Zhuawu, and Assistant Research Officer, Kimonique Powell. The International Trade Working Paper (ITWP) provides the context of the status quo in regards to the progression of WTO negotiations on the liberalisation of Environmental Goods and Services (EGS), providing a map of the developments and discussions that have already taken place regarding EGS trade liberalisation at the WTO. Within this context of current global affairs, this Working Paper proceeds to critically evaluate the opportunities and challenges Commonwealth nations, especially small states and Sub-Saharan African member nations, face in the negotiations for EGS trade liberalisation. This conclusion of this paper focuses on highlighting focus areas for the policymakers of Commonwealth nations to assess to better understand how they may better integrate and lobby for their interests without reaching an impasse during the negotiations.

The Context

Removal of trade barriers and the liberalisation of trade is an important next step in tackling the increasingly dire consequences of climate change to facilitate universal access to effect-mitigating technologies and equipment, improve energy efficiency and expedite the transition to green economic development. Discourse on the importance of EGS began on a global level in 1986 during the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade and Negotiations, by far the largest international trade negotiation to ever take place, wherein the ‘Decision on Trade and the Environment’ and the ‘Decision on Trade in Services and the Environment’ were incorporated as part of the agreements discussed for the creation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The trade negotiations officially ended after 8 long years of debate in Marrakesh, Morocco on the 15th of April 1994 where 123 countries ratified the Marrakesh Agreement that resulted in the establishment of the WTO on 1 January 1995. In the Marrakesh Agreement, the Decisions made during the initial Uruguay Round were formally ratified stipulating the protection and preservation of the environment as well as human and animal lives as an integral pillar of multilateral trade, with the only exception to this rule being in the case where “environmental measures” were being used as tools to restrict trade which is prohibited under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Articles XI and XX (signed in 1947). The significance of the trade of environmental goods and services in aiding countries to achieve climate protection objectives, especially waste management, pollution control and sustainable use of finite resources, gave impetus to the proposal to liberalise EGS trade being brought to the fore during the WTO’s 4th Ministerial Conference, known as the Doha Development Round, in 2001. The Doha Ministerial Declaration was signed during the event and Paragraphs 31-33 of the Declaration outlined explicitly the integral role of environmental issues as a factor for consideration in multilateral trade. Paragraph 31(III) in particular put forward the agenda for “the reduction, or as appropriate, elimination of tariff/non-tariff barriers to environmental goods and services”. Other fields of negotiations during the Doha Round, such as Paragraphs 13-14, also discussed environmental concerns in the fields of agriculture.

Ministers who attended the meeting unanimously agreed to launch multilateral trade negotiations provided it was first determined how WTO rules applied to member states that are signatories of multilateral environment agreements (MEAs) and that the relationship between the trade measures undertaken through MEAs and the WTO Rules was clearly defined to avoid confusion and policy mismanagement. They also vowed to discuss arrangements for the periodical exchange of information between the MEAs and the WTO. Once this was settled, they vowed to reduce and eventually eliminate tariff and non-tariff barriers to EGS trade and instructed the WTO Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE) to study in-depth the effects of environmental measures on market access and provide technical assistance and training for capacity building to developing member states to guarantee that the policies drafted for environmental sustainability are compatible with their development goals. Considering the sheer gravity of the consequences of environmental degradation and the growing evidence of how enabling access to affordable green technology and equipment could both help mitigate environmental harm and provide economic incentives for member states to participate, it was predicted that the negotiations would result in a consensus on mutually beneficial policies and an early conclusion to the discourse.

The Present

Initially, most WTO member states expressed readiness to commit to the negotiations for EGS liberalisation. However, after over a decade of discussions and forums, they have yet to succeed in reaching a multilateral consensus. The crux of the issue lies in the complexity of the definition of EGS that could be used to create legally binding trade rules. Furthermore, liberalising EGS trade involves arriving at a mid-point of compromise for every WTO member, each of which has its own trading strengths and weaknesses, personal interests and agendas. Generally, it is observed that aside from some outlier states, the developed and developing member states are the two opposing groups largely divided over the concept and definition of what makes a commodity or service come under the umbrella of EGS. Developed member states have been at the fore of producing and exporting EGS hence positioning them as the greatest benefactors of the liberalisation of EGS trade which is why they are more adamant about drafting precise parameters for the definition of EGS as well as more legally binding international agreements on lowering tariffs for it. For developing countries, their apathetic approach is not just due to their lacking presence in the export arena of EGS, but also because the current negotiations on the liberalisation of EGS trade do not yet examine non-tariff barriers nor have there been any extensive studies presenting objective and tangible data for developing countries to understand the benefits of EGS trade liberalisation or the adverse impact of their decision to not partake in negotiations.

As for the current progress of these negotiations, experts have discovered that environmental goods have been given more focus in negotiation forums than environmental services despite the fact that they are critical for the functioning and management of environmental goods and technologies. Services comprise over 60 per cent of the environmental industry sector and are explicitly mentioned in Paragraph 31 (III) of the Doha Declaration. The lukewarm response to environmental services’ liberalisation is primarily due to a comparative lack of data on the trade environmental services and the lack of understanding of the complex factors that could help identify the trade barriers for these services. An equally important factor may be the fact that the majority of these services have predominantly been the responsibility of the public sector and municipalities due to which discussions on such services tend to be politically sensitive. In the ongoing negotiations thus far, 52 WTO members, including both developed and developing countries and the EU-27 being counted as one member, have made partial commitments to liberalising trade in environmental services in at least one subsector under the WTO GATS rules, of which 8 are Commonwealth small states and SSA countries. (Table 2.1)

A big stumbling block for assessing the scope of environmental services is how WTO members have looked toward Division 94 of the UN Central Product Classification (CPC) System and the WTO’s sectoral classification list (1/120) though the latter is largely a rendition of the former with a traditional view of environmental services as a subsection of public infrastructure services i.e. pollution control, waste management. Although the CPC encompasses integral environmental services it negates non-infrastructural services which are becoming an increasingly critical part of environmental services such as consulting, engineering, wealth management and construction. Eventually, the WTO members submitted proposals voicing concerns over the lack of holistic inclusion of environmental services and motioned for a revised classification system including the highly disputed S/CSS/W/38 [1] EU proposal. As of yet, however, these discussions remain inconclusive. The liberalisation of environmental services also faces the problem of the inability to lift restrictions on their supply. Up to now, trade in environmental services takes place mainly through Mode 3 [2] (commercial presence) and Mode 4 (temporary movement of natural persons) though these limitations do not benefit the trade of these services, especially now that their trade through Mode 1 (cross-border supply) and Mode 5 (services content embodied in goods) is gradually becoming a norm due to the COVID-accelerated digitalisation across the world. To give an example, wind turbine performance surveillance can now be done in a foreign country (Mode 1) rather than having to set up a physical office in the country of operation (Mode 3). Post-COVID advancement in environment technologies/green technology will continue to grow environmental services that require such technology as their trade becomes diversified and more convenient through Mode 1 supply.

The conceptualisation and parameters for defining environmental goods, despite the prioritised focus, have also not been successfully developed during these WTO negotiations. Thus far the term encompasses a broad variety of industrial goods that have been assessed in different stages of the goods’ life cycles to assess firstly, whether it was produced in a manner that minimises environmental damage; secondly, whether or not it is used to benefit the environment in any manner; and lastly, whether or not it helps mitigate damage to the environment that has already taken place. Based on the mentioned criteria, WTO members have identified two categories of environmental goods that could potentially be liberalised. These two categories consist of (i) goods that are used for the management of environmental degradation, such as oil spill remediation equipment and (ii) environmentally preferable products (EPP) defined as those goods that are not harmful to the environment when produced, used and disposed of and may even have a net positive impact when used to replace harmful counterparts for e.g. bio-degradable disposable cutlery and such materials. Upon assessment of these parameters, several issues arise; the items allotted to the first category may be beneficial to the environment but they are also known to have dual/multiple non-environmental purposes. Similarly, for the EPPs mentioned in the second category, it was found that, ironically, some EPPs have in certain instances substitute items that are equally as environmentally friendly or perhaps even more so than the listed EPPs. As such, creating a finite list of EPPs bears the risk of discriminating against other commodities merely based on the processes and production methods (PPM) which could lead to protectionist policy frameworks in EGS trade tariffs. Another concern which encompasses both categories is their incompatibility with the Harmonised System (HS) used to classify tariffs. The lack of proper filing and classification leads to further difficulty in understanding how to commit to removing tariffs on the group of goods without the risk of leaving out credible EGS or lifting tariffs off non-EGS. According to experts, this is a solvable matter though it will require hefty implementation costs and a long period of time.

For developed member nations, the above-mentioned “list approach” is preferred due to the fact that it is favourable for industrialised countries with a comparative advantage in the export of environmental goods. The list approach aims to combine pre-existing lists of environmental goods as drafted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), both of which have been the reference point for the WTO negotiations. The list drafted by the OECD contains over 200 items with the intention of experimenting with the properties of items to create a deeper understanding of the environmental sector whereas the APEC list contains only 54 items specifically chosen for being easily distinguishable for customs agents and having separate tariff classifications altogether thus making it easier to liberalise their trade. The WTO also consulted the environmental commodity list crafted by the Friends of Environmental Goods, the members of which are the US, the EU, Canada, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Chinese Taipei and Switzerland, containing 153 items. Ultimately, the WTO combined the recommendations from all the mentioned lists to create its own list of 411 products in 2010. Although this list approach is the preferred implementation method in the ongoing negotiations at the WTO, it is acknowledged that it fails to confront non-tariff barriers nor does it provide a robust framework to create a systematic link between environmental goods and environmental services as stipulated in the Doha paragraph 31 (III) mandate. As such, developing member states subsequently put forward the Environmental Project Approach (EPA), also known as the “integrated approach”. The integrated approach suggests simultaneous tariff reduction in environmental products and increased market access to environmental services. To elaborate, this denotes that when an environmental project meets the criteria set by either a designated national authority or is approved during the WTO’s Committee on Trade and Environment in Special Sessions (CTESS) meetings, the goods and services of the project are exempted from tariffs till its end date or upon the termination of the project. It also integrates the list approach by recommending the CTESS categorise all environmental projects, for example creating separate sections for air pollution control and solid waste management, and drafting separate lists of the goods and services involved in that project in hopes that the approach would succeed in attaining a multilateral consensus. Unfortunately, the solution was rejected by developed member states on the basis of its incompatibility with WTO rules and the argument that since all projects had an eventual expiry date, it would be impossible to draft permanent binding policies for tariff and non-tariff barriers.

The current deadlock in negotiations, however, cannot be tolerated for much longer. Global trade remains on the rise; consumption rates are increasing, employment rates are elevating with the rising population and the complex interconnected relationship of these factors is having a drastic and negative impact on the environment. The most prominent changes include waning biodiversity, climate change, and increasing pollution amongst others, all of which are putting immense pressure on already finite resources that are being used at a faster rate than they are being replenished i.e. water, forestlands and forage, minerals, and other such raw materials. This rapidly deteriorating situation across the globe has come into sharper focus following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the concomitant breakdown of global supply chains which has caused a re-evaluation of global trade and highlighted the need to ‘build back better’. Fortunately, these conditions have rekindled a discussion on the liberalisation of EGS as part of the Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions (TESSD) which is a complementary forum to the WTO’s Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE).

The Plurilateral Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA)

Witnessing the series of inconclusive negotiations on the drafting of a multilateral trade agreement for EGS, 14 WTO members, namely Australia, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, Costa Rica, Hong Kong (China), the European Union, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland and the United States, agreed amongst themselves to branch off the main discussion forums and create a simultaneous plurilateral Environmental Goods Agreement (EGA). These members were later joined by 4 more members, namely Liechtenstein, Iceland, Israel and Turkey, and it must be noted that the EU is considered one member therefore in terms of countries as signatories, the EGA has 46. These 46 states represent 90 per cent of the world’s environmental goods trade and aside from China and Costa Rica all of them are developed member states. In terms of Commonwealth membership, Australia, Canada, Malta, New Zealand, Singapore and the UK are the Commonwealth signatories of the EGA with no participation coming from the SSA and small member nations. Such plurilateral agreements are gradually becoming a preferred option not only for member states wishing to find a way around deadlocked negotiations on emerging issues but also because the benefits of these plurilateral agreements can encompass non-signatory members on a most-favoured-nation (MFN) basis without the need for providing any concessions to the signatory parties or the WTO.

The initial 14 members of the EGA first convened in 2012 and agreed to reduce the applied tariffs on all 54 products of the APEC list of Environmental Goods to 5 per cent or lower by 2015. Negotiations officially began in 2014 and the initial success of the plurilateral agreement inspired more WTO members, more so the developed than developing states, to renew their pursuit of environmental goods liberalisation via the list approach. While this was a positive and intentional outcome for the EGA participants, they did not want the EGA to be limited to the reduction of tariffs. They had an ambitious goal for the complete elimination of tariffs on environmental goods but as more and more non-signatory member states got involved in the discussion, the scope was once again brought down to simple tariff reduction and did not encompass non-tariff barriers and environmental services liberalisation as the EGA had primarily endeavoured to. Consequently, and predictably, dialogue on the EGA slowly ground to a halt in 2016 due to repeated disagreements on what products should be included in the expanding list of tariff-reduced commodities. Several member states lobbied to have the list include those goods that comprised a sizeable share of their exports and others rejected adding goods with high tariff values on the list. To give an example, China proposed to include bicycles on the list which, despite being a logical addition as an environmentally beneficial alternative for motorised transportation, was met with opposition from the EU and the US due to the fear that China’s overcapacity in the production of bicycles would overwhelm their respective markets. Additionally, several members voiced concerns over China’s intention to expand market access rather than solely working towards EGS trade liberalisation which has been seconded by research experts Bacchus and Manak (2021) who highlight the fact that whilst China leads in the export of green technology it does not import nearly as much nor has it been successful in the implementation of its domestic policies on environmental rehabilitation. Aside from members “sitting on the side-lines” and focussing on economic incentives, signatory states have also criticised the extension of EGA benefits to MFN non-member countries as unfair “free-riding” notwithstanding the condition that said benefits would only be provided to them when the EGA had a substantial amount of WTO member states became parties to the agreement.

Commonwealth Sub Saharan and Small States’ EGS Trade Portfolio

Throughout the timeline of the multilateral negotiations on EGS, Commonwealth SSA and small states have been disinterested in trade liberalisation due, firstly, to their marginal stake in EGS exports and, secondly, their concerns over the lack of focus on the removal of non-tariff-related barriers that may be harmful to their exports. This Working Paper thus calls for a deeper study of these states’ EGS trade portfolios to create a better framework for their integration into EGS trade liberalisation policies and conceivably better pathways which could offer improved and diversified benefits to incentivise their increased participation in the multilateral negotiations.

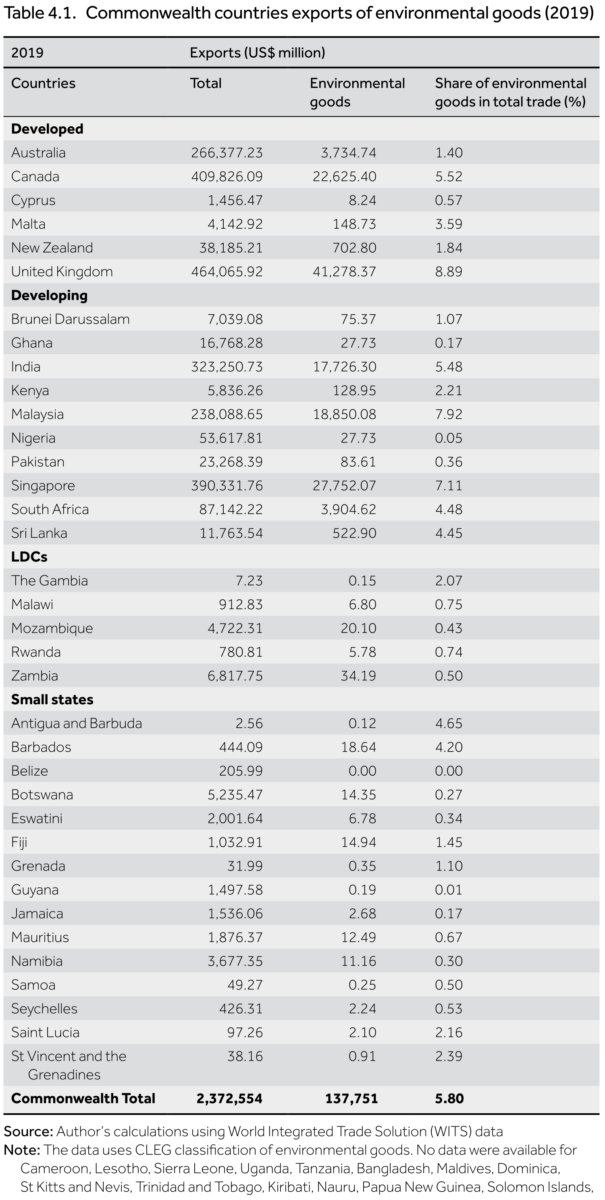

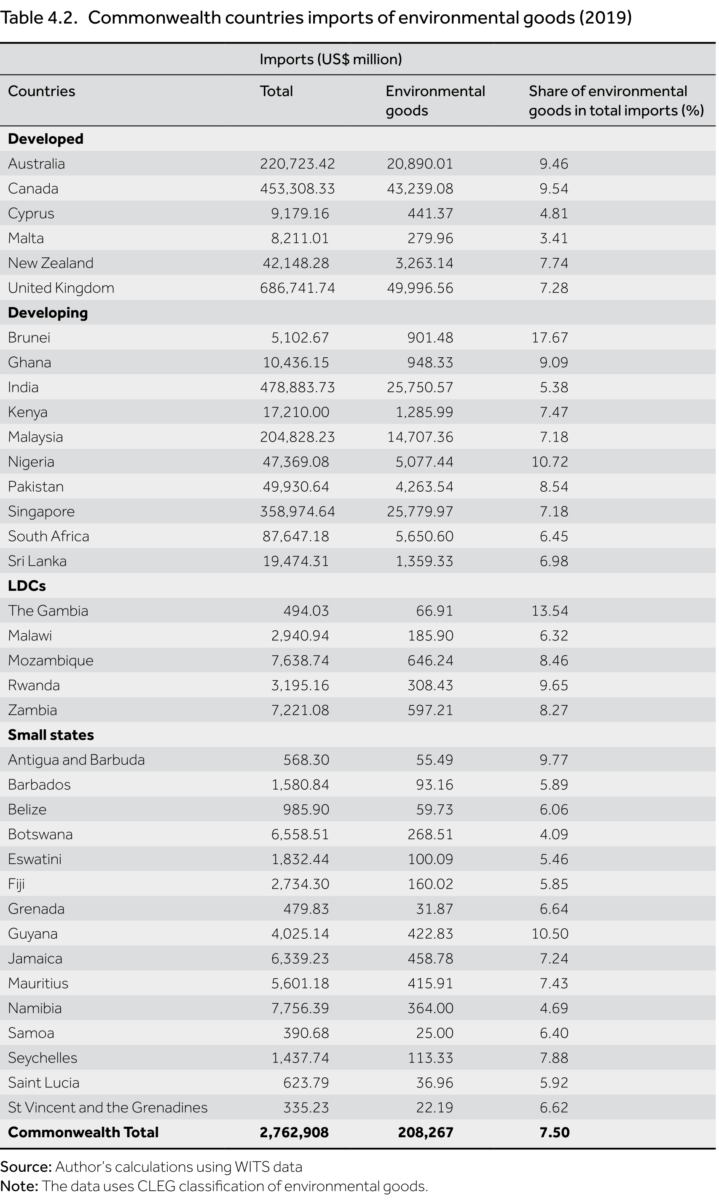

For the analysis of Commonwealth states’ environmental goods trade portfolios, in the absence of a drafted list of environmental goods agreed amongst them, the Combined List of Environmental Goods (CLEG) developed by Sauvage (2014) is employed to extract the approximate data. [Table 1] As can be seen, both Commonwealth SSA and small states are minor players in the export of these goods and their shares are lower than the Commonwealth average (5.8 per cent of total exports) with just one outlier state per category having a share near to the average. For Commonwealth Sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa has the highest share, pegged at 4.5 per cent; as for the Commonwealth small states, more specifically the small island developing states, Barbados’ environmental goods exports are also at a share of 4.5 per cent. Interestingly, as can be seen in [Table 2], with the exception of Botswana and Namibia, all Commonwealth SSA and small states’ imports have a significant share of environmental goods at an average of above 5 per cent with Antigua and Barbuda, The Gambia, Ghana, Guyana, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, and Zambia all having import shares above the Commonwealth total average of 7.5 per cent.

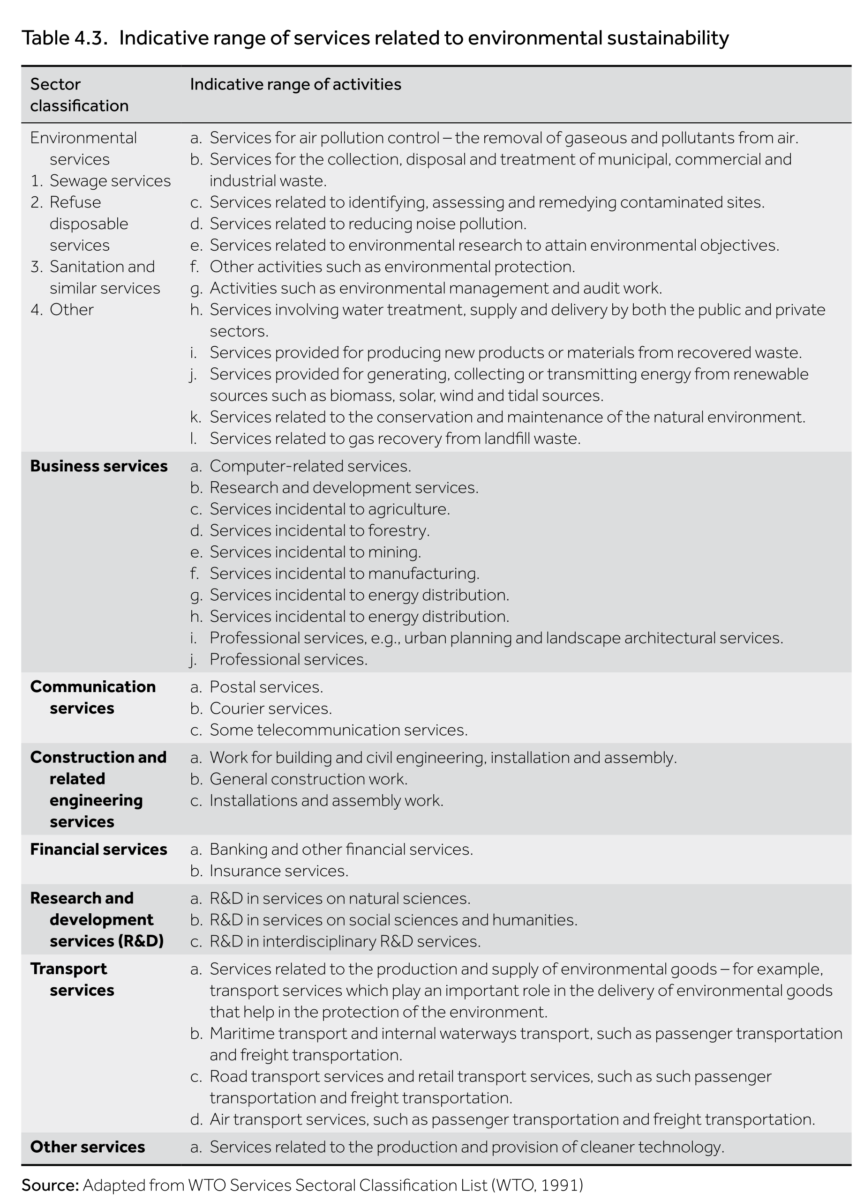

Environmental services are becoming increasingly challenging to separate from environmental goods as a separate component of environmental control and sustainability. With the accelerated pace of economic digitalisation being experienced in the post-pandemic period, more and more modern ecological products require corresponding services as portrayed in [Table 3]. Furthermore, this category of services has grown to expand beyond the limitations demarcated by the WTO’s W/120 (1991) list, now encompassing services that indirectly relate to the protection and management of environmental effects as well as those that aided in the adaptation of sustainable production for e.g. services related to agriculture, mining, energy, distribution and manufacturing. Due to their growing importance across multiple industries, developing countries have been gradually increasing emphasis on green infrastructure and imposing stricter policy frameworks which will in turn increase their demand for environmental goods and technologies. Therefore, the removal of trade barriers, whether tariff-related or not, will not be effective as long as barriers to services are not also concurrently acknowledged and worked upon due to their growing interrelatedness. Experts surmise that Commonwealth nations must draft and implement robust and consistent environmental regulations to increase actual market demand for EGS which will, in turn, generate profits for these goods and services and incentivise developing countries’ participation in their export.

Similar to environmental goods, the SSA and small states of the Commonwealth are notable importers of environmental services, predominantly services required for handling advanced technological equipment used for the mitigation of climate change including renewable energy production maintenance, optimisation of centrifugal blowers for methane capture projects etc. The restrictions put on these services due to the lack of robust regulatory frameworks greatly hinder services primarily provided via Mode 3 and Mode 4 inputs for environmental projects. The restrictions include horizontal limitations for instance investment approval requirements, time-consuming processes for extending stays for hired labour, and capital remittances to name a few. Another obstacle is the lack of these states’ commitment to core environmental services (sewage, refuse disposal, sanitation and other such services) with only 8 (Lesotho, Rwanda, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, The Gambia, Tonga and Vanuatu) of the 35 SSA and small state member countries party to these scheduled commitments. With the global climate barreling towards a rapid increase in temperature and unstable weather conditions becoming more widespread and less manageable, it is absolutely critical for these Commonwealth nations to pull ahead in their understanding of the range of services required for the betterment of the global ecosystem and their responsibility to uphold core environmental services. As a consequence of their better understanding, they may identify potential export opportunities that may be reaped upon the removal of EGS trade barriers.

Commonwealth SSA and Small State EGS trade interests amidst a transforming global economic and trade landscape

The global trade and economic landscape have been shifting since the beginning of 2001, and not in a good way. As mentioned, growing global trade has created a complex relationship between rising production and consumption, increasing job creation as the population surges and the pressure put on finite natural resources. The international community of activists have been calling for international trade and economic institutions to cease the prioritisation of industrial growth in the pursuit of economic development that is accelerating already alarming levels of deforestation, water scarcity, land degradation, greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution amongst other dire consequences. As the impact continues to cut deeper, governmental and supranational institutions are urged to draft policies and initiatives that support only those forms of economic growth and development that guarantee that world trade and environmental objectives are consistently mutually supportive. One such example is the steady growth in renewable energy since the 2000s which has motivated governments to undertake more clean energy projects. As global trends shift towards the normalisation of environmental due diligence in trade, developing countries’ interest in liberalising environmental goods, especially related to wind and solar energy which they have a comparative advantage, has been garnering varied interest depending on their export portfolio, trade policy configuration and productive capacity.

Fortunately, the growing awareness of the importance of EGS trade has increased the market size from US$866 billion in 2011 to US$1.12 trillion at the end of 2017 and is expected to surpass the US$2 trillion mark by 2025. Aside from growing awareness of the global masses, increasing domestic environmental regulations that governments are implementing to fulfil their multilateral environmental agreements, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), are exerting greater pressure on companies to “go green” and work towards widespread adoption of cleaner technologies. According to research by de Melo and Solledor (2018), environmental regulations increase trade in EGS and as such the liberalisation of EGS will become paramount for the transition to a global green economy. Concurrently, it is pertinent to bear in mind that this pace must remain on an upward trend to counter the growing costs of rising population and consumption; for example, global solid refuse production is expected to jump from 2012 volumes of 1.3 trillion tonnes to 2.2 billion tonnes by 2025 and the annual waste management costs will rise from US$205.4 billion to US$375.5 billion for the same timeline.

Developing Commonwealth states are undergoing several changes stemming from climate change, particularly SSA and small member states. The economic ramifications are not yet fully understood though these member states will face the brunt of them due to their comparatively higher geographical susceptibility to the physical impacts of climate change as well as the weak capacity for adaptive measures in both their institutions and their domestic household infrastructure, especially in regards to their technical and financial capacity. Agricultural yield outputs are predicted to fall 20 to 30 per cent, perhaps even 50 per cent, by 2050 thus these member states must act immediately to normalise environmental regulations in their trade policies and assess to mitigate all economic activity that impacts their environment. These developing states should also guarantee that adequate research and due diligence are conducted on the impact of extracting resources used to produce environmental goods, such as lithium, cobalt and other minerals, to ensure that their EGS trade is sustainable in the long term.

The Future: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Way Forward.

Potential Opportunities for the Developing Member States

The Working Paper maps out how the lowering of trade barriers for EGS is critical for the promotion of greener trade across the globe, and how participating in the negotiations on how to go about EGS trade liberalisation is essential, particularly for developing countries to have their voice and interests taken into consideration. The reduction of import costs of EGS will promote competition and increase the productivity and expansion of EGS production companies that are committed to environmental sustainability which will concomitantly weed out inefficient firms involved in “greenwashing” [3] during the natural progression of specialisation, economies of scale and innovation that all product and service trade experience as their markets mature. Even if the environmental and climate change factors were to be left out of consideration, Commonwealth SSA and small states can capitalise on the production of EGS to diversify their economies, expand market access and galvanise their economic infrastructure. Active development of productive capacity for environmental goods and provision of green services could allow these states to gain a comparative advantage in niche markets and allow them to better lobby their interests in the ongoing EGS trade liberalisation negotiations. This will result in efficient and, most importantly, equitable disbursement of EGS based on each country’s respective needs and local capacity. As supply chains for EGS diversify and strengthen, innovation will gradually flow backwards, allowing resource-efficient technologies to become more widespread. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), members of the Least Developed Country (LDC) category are positioned to benefit the most from EGS trade in terms of capacity building and overcoming hurdles they face in participating in the EGS trade due to protectionist policies several developed states have implemented, provided their voice is guaranteed a platform in the negotiations, which is something the WTO must guarantee.

As the developing member states maximise the benefits of trade liberalisation, they will see an increase in South-South trade which has the potential to promote parity in tariffs on both raw materials and manufactured goods resulting in value-added processing. This will in turn generate more jobs, especially where the value-adding processes are quite labour intensive. Moreover, this is an opportune pathway for developing states to not only penetrate existing green export global value chains but also create new regional value chains for outsourcing parts of the production process of EGS to other nations, especially given the unique bilateral cost advantage Commonwealth nations have. Since green technologies and services are quite complex and modular, many of them have to be imported from nations with more advanced technological infrastructure or raw materials have to be exported for processing e.g. waste can be sent to countries that have the most sophisticated processing capabilities to help the origin country manage their waste and also aid in their transition in becoming a more climate-neutral, resource-efficient circular economy. In terms of exports, the export of technologies and training for developing states to operate and produce such technologies themselves can promote them to high-productivity sectors which will enable a substantial structural transformation which may even help graduate them from the developing nation category whilst improving the environment. An example is the use of technology to improve their cooking appliances’ use of fuel which will cause a notable decrease in indoor air smoke pollution and at the same time lessen the burden on their energy production sectors, therefore, allowing them more time and resources to focus on innovating ways to use cleaner energy to mitigate ecological degradation.

Commonwealth SSA and small states are strongly recommended to collaborate with each other to develop common approaches to tackle climate change as well as to take concerted trade and investment-related actions to promote the mutually-beneficial and non-discriminatory liberalisation of EGS trade. Additionally, they can instate checks-and-balances mechanisms in their trade regimes and hold each other accountable for transparency and predictability, particularly in regulatory measures and standards for creating mutually beneficial markets benefitting businesses as well as the environment. One such example is the trade liberalisation of climate-smart agricultural landscape management that will also enhance agricultural output and upscale the sector.

Challenges for the Developing Member States

Despite the immense positive potential that EGS trade liberalisation may bring, this Paper has discussed at length how Commonwealth SSA and small states have been generally apathetic to the WTO negotiations, mainly due to the (current) lack of a significant stake in the export of environmental goods; such as in the case of the 2016 EGA, only one-third of their goods exports destined for the EGA’s member states are listed for negotiation. Commonwealth states are predominantly commodity exporters that are agriculture, forestry and mining heavy; even their services exports revolve around these sectors. Because their commodities are extractive in nature, environmental benefits are mainly derived from the production processes, environmental goods’ trade liberalisation is bound to affect them disproportionately due to the nom-tariff measure they may face especially when importing states impose higher standards of production requirements. And since these SSA and small states, at the same time, import many environmental goods they rely on tariff revenues themselves, and the reduction or elimination of these tariffs proposed in the WTO negotiations, many indeed end up harming their income and have ramifications for their developmental and special progress.

Subsequently, they may also be negatively affected by the surge of EGS imports the trade liberalisation may bring about which will be a challenge for their limited capacity and technological expertise to compete against. Virtually all avenues of trade liberalisation of EGS require states to have the financial and technological capacity to adjust, which these member states need time to develop, both within households and national institutions. Even in cases where the SSA and small states show a willingness to participate in multilateral discussions, they are unable to expend influence on the discussion and get their say in which EGS are admitted into the list for tariff reduction. The WTO and developed member states must provide a fair and equitable platform for these developing states to help them actualise their climate protection and sustainability goals.

The Path Forward

This Working Paper analysed the obstacles Commonwealth developing states face when considering participating in the WTO discourse on EGS trade liberalisation. These issues are essential for their National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) as well as their progress towards their respective Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for their GHG mitigation and other ecological goals ratified under the Paris Agreement. These developing states find the current WTO list, largely drafted by developed WTO member states, to be highly limiting and comprising products that they are net importers of, and this is the main crux of the issue as stated in Section 1. Therefore, any list that is to be mutually beneficial for all members of the WTO and Commonwealth, must encompass those goods for which they have a comparative advantage in terms of exports. On the other hand, SSA and small states of the Commonwealth must also meet their developed counterparts halfway by including goods with multiple uses into their definition of environmental goods, provided they are also of potential interest to them. They must be flexible which may impact them negatively in the short term to allow themselves space to develop policy space and specialisation in these products so they may eventually earn profit for them; for example, list of the previously mentioned multiple-use products that may decrease their revenue collection. For those environmental commodities listed based on their processes and production methods (PPMs), they affect developing member states more so than developed ones as the former’s exports are extractive in nature and the latter tends to enforce stringent national requirements for them. It must be stressed that these import restrictions can be in violation of the GATT 1994 Article III which obligates its signatories to grant the imports ‘treatment no less favourable than that accorded to like products of national origin’.

For Commonwealth SSA and small states, liberalisation of environmental services trade may require them to revise their pre-existing services commitments made in the trade agreements of which they are signatories. The reason for this is the fact that since environmental services include many services with multiple uses, member states may have already made commitments to the value of these services through other trade agreements; as such, they may have to revise the conditions and valuations of said services if they happen to be clashing in any manner to the commitments they may make to the liberalisation of environmental services. This is especially the case for those services commitments that are listed as “Unbound” [4] by the GATS Schedules of Specific Commitments.

The WTO negotiations on liberalising EGS trade provide an opportunity for developing member states to demand developed counterparts and the organisation to share and transfer technology essential for environmental purposes and production, at subsidised rates. Co-operation in trade liberalisation will enable multilateral trade commitments to aid countries in harnessing trade as a tool for accelerated, inclusive, and sustainable development. This Paper has proven adequately that trade-driven economic development and actions on environmental and climate change can only be executed in tandem; prioritisation of one over the other will result in ineffective execution of both priority areas. Be that as it may, developing member states are still in need of differential and prioritised treatment to be capable of developing the policy space and trade flexibilities to be able to successfully liberalise their EGS trade.

The risk of protectionist policies disguised as environmental concerns, especially where international consensus on the matter is arbitrary, can not be overstated. To prevent such asymmetrical and problematic trade policies from being implemented, developing member states are implored to be present in the WTO decision-making forums to ensure their interests are not overridden by rules they did not contribute to making, especially considering the fact that their economic development and livelihood are impacted by climate change much more so than any other party. The ultimate goal of these negotiations, and the global drive to reverse climate change, is the creation of a mutually beneficial outcome designed to account for all international, regional and local perspectives.

3. Refers to when companies convey a false or misleading impression of their products/services are environmental sound or ecologically sustainable

4. When services sectors or sub-sectors are listed as “Unbound”, it means some of the GATS rules are not applied, and when the mode of supply for these services is listed as “Unbound” it means that they are to remain consistent with market access and national treatment unless new rules inconsistent with these conditions are introduced by the WTO member in the future, which they may do so without compensating the WTO for inconsistency with the GATS rules