Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Growth and Opportunities in the Commonwealth

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG): Growth and Opportunities in the Commonwealth

This newsletter is based on the report titled “Environmental, Social and Governance Practices for Value Creation in the Commonwealth” by the Economic and Sustainable Development Directorate of the Commonwealth Secretariat (hereon: Secretariat), released on 20th April, 2023. The report was authored by Dr Ruth Kattamuri, Senior Director of the Economic, Youth and Sustainable Development Directorate; Sanjay Kumar and Delia Cox, Advisers for Debt Management at the Secretariat; and, Alex Lee-Emery, Research Officer at the Economic, Youth and Sustainable Development Directorate.

External data was used in conjunction with the aforementioned report, including publications on ESG from Deloitte, the Corporate Finance Institute and Diligent; also, SolAbility’s Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index 2022.

This newsletter provides a conceptualisation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices and highlights the data-driven evidence of the positive correlation between greater emphasis on ESG framework implementation and sustainable economic growth critical for long term value creation in the Commonwealth. Furthermore, this newsletter elaborates on how the financial benefits of non-financial ESG parameters can only be fully actualised with due diligence against the risk of companies committing “greenwashing” and awareness of the current underdevelopment of a globally standardised ESG assessment methodology as well as the asymmetrical maturity of ESG regulatory and policy frameworks across regions. This newsletter concludes with a brief outline of policy recommendations suggested to be adopted by Commonwealth nations for the uniform adoption of ESG principles.

E-S-G: What do the letters mean and why are they important?

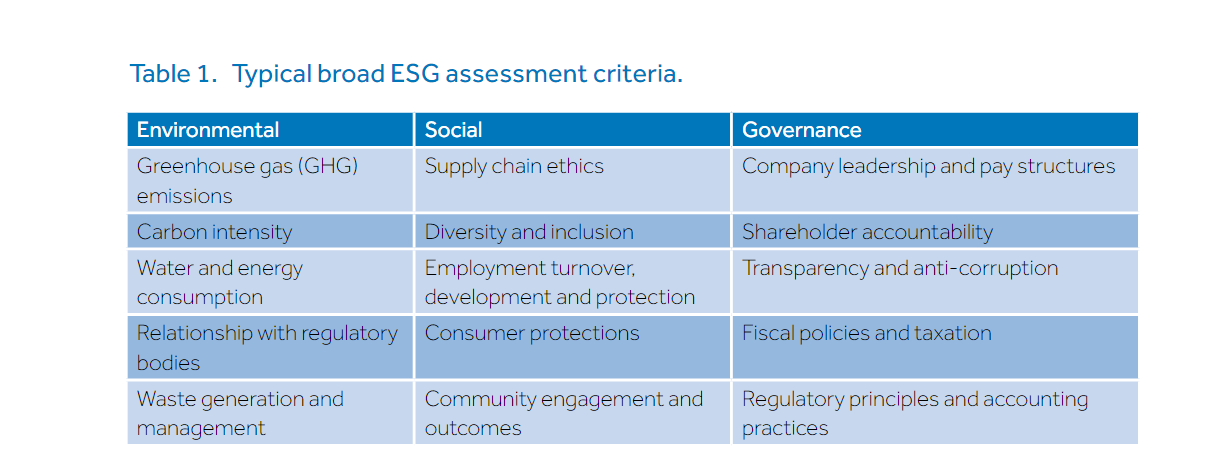

ESG in full refers to “(E)nvironmental, (S)ocial and (G)overnance” principles. While no official definition of ESG exists, it is agreed to be a holistic management framework of standards for all business-centric stakeholders involved in the structuring of organisations to understand and measure how well their companies/institutions are performing to offset risks and harness opportunities related to environmental, social and governance indicators. The “E” pillar of the framework pertains to the responsibility towards the preservation of all organic resources in our natural world; it encompasses policies and strategies to mitigate harmful emissions, maximising product lifecycles, decreasing pollution and planning initiatives for tackling climate change and deforestation amongst other green initiatives. Within the ESG Investing framework, “green investments” are prioritised and environmental risks are taken under serious consideration. The “S” pillar alludes to an organisation’s labour laws and practices and its overall relationship with internal and external stakeholders with particular emphasis on human capital management and impact on the local communities of the areas they operate in. The “G” pillar of governance, also known as corporate governance, is largely concerned with the logistics and leadership of an organisation; ESG analysts look into the mechanisms in place to secure shareholder rights, the makeup of the board of directors with special parameters in place to scrutinise board diversity, the sustainability of their compensations and benefits, best practices of the company’s human resource management as well as monitoring levels of lobbying, corruption and any political activity across the board plus all employees of the organisation.

Source: Commonwealth Secretariat

The genesis of ESG can be traced back centuries, dating back to religious commandments banning investments in slave labour. But the modern concept of ESG began when, in the 1950s, workers’ unions convened and pooled their pension funds into initiatives for the betterment of their communities and the environment, which included affordable housing schemes, health facilities and environmental rehabilitation programmes. In the 1960s, socially responsible investors began scrubbing stocks or even entire industries from their portfolios which they morally disagreed with for e.g. stocks and businesses that supported wars, racism or those that expanded with excess disregard of community misplacement or environmental degradation. This led to an international snowball event whereby in the 1980s and 1990s it had become almost a norm for investors to seek out companies in the global investment market that focussed on social responsibilities, especially due to the fact that research showcasing empirical evidence of better financial opportunities borne out of the principles and standards being adopted by these companies.

In 2000, then-Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, established the United Nations Global Compact Initiative as a call to action for companies to “align strategies and operations with universal principals on human rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption, and take actions to advance those goals”, which was a milestone as a first (non-binding) UN-to-businesses pact of its kind declaring the worldwide initiative to adopt and monitor sustainable and socially responsible policies. The Global Compact, in collaboration with chief executive officers (CEOs), asset managers, consultants, regulators and research analysts from 55 leading financial institutions, published the report titled “Who Cares Wins” which popularised the term “ESG” and its framework of recommendations. Around the same time, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Finance Initiative released a legal document mapping out guidelines for assimilating ESG parameters in financial valuations for institutional investments. These two reports created the foundation or the launch of the UN-verified Principles for Responsible Investment in 2006, a network of over 4,900 members (financial institutions, asset management firms and consulting firms) that, as at December 2022, manage approximately US$121.3 trillion in assets. The PRI’s prime role is to forward its six principles of ESG adaptation and commitment to help support its international network of investor signatories in incorporating ESG in their decision making and ownership decisions.

A PwC report predicts an 84 per cent increase in the global value of ESG-related assets under management to a global value of almost US$34 trillion. It also states that ESG assets will comprise 21.5 per cent of total global assets under management, which would mean that these ESG assets are expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of a whopping 12.9 per cent. In 2020, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) reported that approximately US$35 trillion assets under management for the year were undergoing some sort of ESG screening process, despite peak COVID-19 disruptions.

A Snapshot of Global ESG Practices

The Secretariat defines the role of ESG in investment as a ‘concept to assess the viability of proposed investments and projects based on their expected environmental and social impact and governance practices”. The concept expects companies looking to be invested in to uphold the principles and parameters of the ESG framework and puts the burden of proof on investors to be cognizant of the instruments they are investing in and make sure they have a positive impact on the environment, fortify global supply chains against disruptions, champion workers’ rights and uphold their corporate social responsibility.

ESG parameters are not just a means to increase market value and attract the interest of investors looking to invest in sustainable and socially responsible financial instruments. There is empirical evidence highlighting an estimated loss of US$1.26 trillion in revenue by 2026 due to supply chain disruptions as a consequence of environmental and climate risks. As a consequence of these disruptions and the additional charges levied to work around the disruptions, it is estimated that this may incur an additional cost of US$120 billion for private businesses across the Commonwealth. Moreover, firms across the world, both public and private, may lose out an average of 6 per cent of their market capitalisation if they fail to mitigate ESG risks, especially if they experience severe ESG-related missteps. Thus far, efforts toward ESG-adoption into regulatory and policy paradigms has been growing asymmetrically across regions, with Europe and North America at the fore, owing to their comparatively more mature regulatory infrastructure and history of mainstreaming ESG risk management, and the Sub Saharan and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) lagging behind the most.

Although annual investments in clean energy and comprehensive public services for climate adaptation have been increasing considerably, 2022 estimates from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) found that the current progress of developing nations towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) by 2030 continues to struggle with an annual funding gap of US$4.3 trillion. International financial institutions have been developing frameworks to assimilate and incorporate ESG concepts into all their project feasibility research and public investment decisions; In 2018, the World Bank released its “Environmental and Social Framework”, mapping out commitments to ten standards of sustainable practices and risk management called the Environmental and Social Standards (ESS) pertaining to the measurement and management of environmental and social risks, labour conditions, resource efficiency for pollution prevention, communal health and safety, restrictions of land acquisition and involuntary resettlement, biodiversity and natural resource conservation, underserved traditional local communities, cultural heritage, financial intermediaries and disclosure of stakeholder information. For developing and developed nations of the Commonwealth, it is recommended for their national and subnational governmental institutions to study these IFI frameworks to calibrate their own EGS frameworks to conclude more effective public investment decisions and nurture private-public partnerships (PPP) that are most suitable for the needs and requirements of own their regions of administration. Prior to these steps, however, governments should guarantee that they have the necessary capacity to meet international standards from which they base their ESG frameworks, to ensure sustainable foreign direct investment (FDI) and domestic investment inflows.

The Impact of ESG on Financial Performance and Investment Returns

Compared to traditional investing, it is suggested that ESG parameters can result in bigger and better output for shareholders via more productive business outcomes, better returns as compared to conventional portfolios, more abundant welfare for people and more sustainable economic growth overall without having to jeopardise the environment. To gain an empirical insight on the correlation between ESG and improved financial performance, over 1,000 research papers on ESG published between 2015 and 2020 were assessed and results showcased that 58 per cent of the corporate studies saw a positive correlation while 34 per cent presented neutral and mixed results and 8 per cent portrayed a negative relationship. Research looking into the correlation between ESG and financial performance observed 5 overarching ways that ESG generates value for firms:

- Bolstered economic growth: Attracting long term customers with sustainable products. Achieve better resources as a result of improved community and governmental relations.

- Cost reduction: Lower energy fees and reduced natural resource input.

- Minimising regulatory and legal intercession: Greater strategic freedom as a result of less strict regulations on advertising and comparatively less penalties. Greater share of government subsidies due to community confidence.

- Uplifting productivity: Higher levels of employee motivation and higher levels of talent retention due to established social credibility

- Optimised asset selection and investment allocation: More investment returns due to allocation of capital in sustainable and long term financial instruments. Also evade risks of short term payoff investments with long term environmental risks.

In contrast to traditional investment performance it was noted that ESG profit levels were not significantly higher than those of conventional investing portfolios, a fact that is often forwarded as an argument by those who claim ESG to be no more than a corporate formality. It is also true that ESG disclosures on their own are not sufficient for improving financial performance. The impact of ESG on financial performance is often understated because performance becomes more and more pronounced over long term horizons. Furthermore, ESG measures drive higher financial performance returns through improved mediation, improved risk management and most importantly, by insulating portfolios with downside protection during global, regional and national social or economic crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as researched by the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing in 2021, in a sample of 3,000 funds all sustainable equity funds outperformed their counterparts by a median of 3.9 per cent; another study analyzing 26 ESG indices also observed 24 of the sample indices outperforming the conventional indices. A more recent study by Morningstar highlighted how, in the overall decline of value across global funds as a result of the global economic recession, the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the consequent inflation, ESG funds had incurred the least loss.

This is especially critical as we navigate the post-pandemic economic arena that has proved to be vastly dissimilar to the economic ecosystem prior to the pandemic and its consequences, both the negative and the unexpected technological and innovative positives. Governments across the world are prioritising insulation against economic shocks and sustainable economic recovery; as such, ESG frameworks in investments and asset management will help guide for improved private and public fund allocation and more reliable tax revenues while screening projects to ensure national and international climate change targets and social and governance standards are being met and maintained.

What are the challenges in implementing effective ESG frameworks?

The recent interest in ESG has been unprecedented and immense. Many have called for the adaptation of ESG frameworks, however, many have also raised rightful concerns on the lack of verified and feasible ESG standards on which to base policies and organisational restructuring.

A common concern for both public and private sectors is the absence of a precise, clear and standard definition of ESG that can apply across all industries. Due to this, various assessment methodologies produce variable reports and inconsistent scores more so dependent on the chosen indicators rather than consistent comparisons. A 2022 study looking into the correlation between different ESG assessment providers saw a 54 per cent correlation between their assessment indicators; this percentage became even lower when disaggregating and assessing the qualitative social and governance scores. The incorporation of environmental, social and governance indicators into a single index without proper standardisation and presentation of each individual indicators standards and weightage also incubates erroneous results; for example, if a company has subpar performance for environmental initiatives and policy changes, it can still end up having a satisfactory overall score if it scores above average in the social and governance indicators. Moreover, these indices run the risk of masking inherent social and environmental trade-offs companies have to make. On the contrary, traditional stock and company credit ratings have a 99 per cent correlation.

A lack of cohesive and comprehensive definitions, standards and parameters can result in “greenwashing” which describes the false claims companies and organisations make by inflating their ESG scores, particularly when self-reported, or presenting them in a misleading manner. Considering the increased attention and favour being given for high ESG scores, companies may miss the actual intent of ESG frameworks for the betterment of social and environmental outcomes and focus solely on the profit incentives and increased investor interest. Be that as it may, one possible solution has emerged with notable consensus which is the recommendation to establish working groups to agree upon common taxonomies across the regions without them being alterable across different jurisdictions. An example being the ambitious 2020/852 European Union (EU) Regulation “on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment” currently being developed that has outlined six major environmental outcomes (climate change mitigation; climate change adaptation; sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; transition to a circular economy; pollution prevention; and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems) with three distinct tiers for the level of contributions made by companies. “Substantial contribution economic activities” is the highest tier, after which is the “enabling economic activities” tier and the “transitional economic activities” tier based on a descending order of level of contributions by the firms. Provisions to update and maintain the criteria are also clearly stipulated.

Within the Commonwealth, Australia, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa and the United Kingdom have made significant progress in developing taxonomies for green financing. Developed countries tend to fare better in the current ESG policy environment than developing nations as they are better able to incentivise the adoption of trustworthy standards and development of reliable and readily available ESG products. Developed nations therefore have low investment risk even though, ironically, developing nations stand to benefit more from the benefits of ESG. In some cases, such as in the case of the Commonwealth Small Island Developing States like Fiji, climate change is the main cause for the high risk ratings they receive, despite being amongst the lowest contributors to factors of environmental degradation. In regards to access to quality and consistent sustainability data on which to base ESG framework, both developed and developing nations struggle, despite the influx of articles and publications on the benefits of ESG. Research institutions should help design a framework that facilitates modular and transparent reporting requirements for each pillar. In parallel, considering the reality that a successful ESG framework will take time to develop, firms such as The Economist have suggested companies to only focus on lowering greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions and suggest that investors consider this the most overarching indicator in the face of the scale and immediacy of climate change. Private sector companies in particular are advised to cooperate closely with national and provincial governments to achieve Net Zero and SDG goals by 2030.

Currently, policy instruments are being pushed forward to decree businesses to disclose their emission levels and other outputs that impact environmental health. If these disclosures are guaranteed to be frequent and transparent, it will greatly increase stakeholder awareness of ESG issues, creating an added layer of pressure onto the firms to disclose transparently and commit to more sustainable initiatives. In 2022, the UK became the first Commonwealth nation and G20 nation to mandate 1,300 UK-registered firms to disclose their climate-related financial statements; this policy came as a recommendation from the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, an industry group established at COP’21. Under this mandate, companies and limited liability partnerships (LLPs) with over 500 employees will be required to present a copy of governance arrangements undertaken to assess climate-related risks and also opportunities as well as a description of the methodology they will use to execute this task; how these identification processes are embedded into their overall risk management policies and business models; the timetable of their assessments; and, a description of targets used to manage climate-related opportunities and key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess progress against these targets along with a description of the calculations on which the KPIs are based.

As countries gradually work towards their Net Zero deadlines, capital will continue to be allocated to refining and developing robust and standardised ESG assessments and frameworks, the systemic transition to mainstreaming ESG investing will continue and in time will present more robust and objective evidence on the effectiveness of ESG adoption for the future of global sustainable economic development.

ESG and the Role of the Government and the Public Sector

With expenditure averaging 36 per cent of GDP annually, governments are amongst the most prominent institutional investors across the world. They are responsible for the employment of several thousands of civil servants and are directly and indirectly one of the biggest contributors to waste and carbon emissions. They are also directly responsible for the management of sustainability issues and creation and implementation of sustainable development solutions. By mainstreaming ESG practices into the policy frameworks of the main governmental organs and the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), it would present immense potential for the acceleration of ESG adoption in national and subnational fiscal decision making and infrastructural project management. Furthermore, as IFIs have begun to demand thorough social, environmental and governance assessments and plans of action for progress monitoring as a requisite for financing projects, governments that adopt ESG standards will be more aligned with IFI standards and can more effectively build capacity to perform well within these frameworks to attain improved access to climate-focussed financing.

Global public sector reporting, despite the aforementioned positive outcomes of it, has been lacking and inconsistent. According to the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) global survey conducted in 2021, only 20 per cent of the respondents confirmed that sustainability reporting was incorporated into their company’s policy mandates and less than 50 per cent actually produced annual sustainability reports; of the companies that did publish them, only 37 per cent stated that they were confident in their in-house skills to deliver comprehensive findings. Without commitment to sustainability reporting by the public sector, ambitious climate change targets can not be met with the initiative of private sectors alone.

Sovereign wealth funds and state-owned pension funds are particularly suitable for ESG frameworks due to their public ownership and inclination towards long-term and maiximised returns. These sovereign funds are seen as representatives of the government’s priorities and goals for the future and many countries have hitherto allotted funds into separate ESG funds, emission budgets and Net Zero targets to be met by or before 2050. According to the Net Zero Tracker 2022, all Commonwealth nations have set aside capital emission reductions and targets which cover 40 Net Zero commitments. Due to the burden of answerability to the public communities, public sector and sovereign funds dedicated to ESG parameters are bound to require greater levels of transparency and reporting. Taxpaying citizens and community stakeholders can demand their right to be kept informed and understand how exactly the fund is being spent. The private sector organisations are also advised to match this level of transparency and reporting to the public, particularly those that have the support of public financing. ESG metrics have also been found to be compatible and useful when integrated into the creation of debt portfolios and sovereign debt management systems due to the uptake in interest by sovereign bond investors. These investors are encouraging research into ESG assessment which has also made credit rating agencies acknowledge the importance of ESG risk assessment and several renowned agencies like S&P, Moody’s and Fitch have all declared their commitment to adjusting credit risk ratings with ESG parameters.

- Green bonds: In 2007, the European Investment Bank introduced the “Climate Awareness Bonds,” marking the inception of green bonds. Subsequently, other supranational issuers, including the World Bank, followed suit. Green bonds are designed to raise funds specifically for projects that have a beneficial environmental effect. These projects can encompass various areas such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean transportation, green buildings, wastewater management, and climate change adaptation.

- Blue Bonds: In October 2018, the World Bank played a key role in the introduction of Seychelles’ sovereign blue bond, marking it as the world’s first of its kind. These unique bonds allocate the raised funds specifically to support marine-focused projects, including the preservation of biodiversity, the promotion of coastal economies, and the development of sustainable fisheries.

- Social bonds: Social bonds have gained significant popularity as a type of fixed-income product, and their issuance is predominantly led by multilateral development banks (MDBs). These banks often have access to a pipeline of projects that meet the criteria for social bond eligibility. Examples of such projects include initiatives related to food security and sustainable food systems, local economic development, affordable housing, and essential services such as healthcare. To help support issuers verify transparent, financially and socially sound and sustainable projects, Social Bond Principles (SBPs) were released by the International Capital Market Association in 2021.

- Gender bonds: Gender bonds are a recent development, and there is currently no official definition in place. However, they can be broadly understood as bonds that aim to promote women’s empowerment and gender equality. International initiatives like the ‘UN Women Empowerment Principles’ and the ‘2X Challenge’ can serve as guidelines to identify suitable investment activities and assess the benefits and impacts of gender bonds. Notable examples include the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) issuance of a US$90 billion gender bond in 2017 and the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) commitment in 2020 to fully support Indonesia bank OCBC NISP’s gender bond.

- COVID-19 bonds: These bonds were created as a result of the rising demand for diversified financial instruments following the global onset of COVID-19 in 2020. These bonds specifically raise finance as insulation against global economic shocks and to reverse the adverse effects of the pandemic to drive more socially-cognizant economic recovery strategies.

- Sustainable bonds: Sustainability bonds are a type of bonds that are used to exclusively fund or refinance a combination of environmental and social projects. They provide a broader scope of investment opportunities and cover various project categories. While the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer a wide range of possibilities for issuers to contribute to the 2030 Agenda, SDG bonds are still in the early stages of development. The growth of the SDG bond market can be facilitated by expanding the range of eligible assets and project categories, along with providing clear guidance on how the bonds align with the SDGs.

- Transition bonds: Transition bonds are utilised to raise funds specifically for projects that are dedicated to pre-defined activities aimed at facilitating climate transition.

ESG bonds are a particularly good choice as they are usable by a variety of stakeholders looking to fulfill SDGs from corporates, governments, banks and municipalities to retail investors and the general public. Compared to the equity market, the bond market is double in size. Bonds may be a more attractive choice due to the fact that, compared to equity, bonds have more stable return rates and price fluctuations are also more stable and predictable with less risk of significant and sudden capital loss due to short-term changes in the market. Due to the current appetite for ESG-related bonds, the costs of debt servicing on these bonds is lower than the costs of conventional bonds, according to the Secretariat.

The green bond market is the most prevalent ESG-related bond and remains central to the ESG bond ecosystem, still growing at an annual average rate of 20 per cent. Green bonds are popular amongst investors as they are perceived to add value without increasing any form of risk and also because the impact measurement of green bonds is more straightforward and quantifiable since it is easier to make quantitative measurements for environmental parameters as compared to social or governance indicators. Green bonds are also easier to “ring fence” due to the investor confidence in their advantages and positive impact, whereas social and governance bond markets are still considered “niche” and have not been able to gain as much and as diverse support. Such asymmetries notwithstanding, social bonds gained substantial traction in 2020 as a means to finance improved healthcare infrastructure and services during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, social bond issuances have predominantly been dealt by government agencies and supranational and local authorities while corporate issuers, including banks and non-financial issuers, have struggled to procure assets or potential projects that could fit the requirements of the SBPs.

Lastly, ESG bonds do carry financial stability risks that stakeholders and policymakers, especially those in emerging markets, must be aware of and monitor closely. The investor base for these bonds differs from traditional investors and may be more sensitive to global financial conditions, especially due to the technology-focused nature of many ESG indices. This becomes a significant factor to consider in the present policy landscape, as central banks in advanced economies are increasing interest rates and scaling back pandemic-related policy support.

Assessing ESG Models for the benefit of the Commonwealth

Global economic growth is projected to decelerate from an estimated 6.1 per cent in 2021 to 3.6 percent in 2022 and 2023 (IMF 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruption globally and will have long-lasting effects, including increased poverty and debt that pose a threat to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As countries recover from the pandemic, they face multiple challenges, such as rising commodity prices, global inflationary pressures, high levels of debt, geopolitical instability, conflicts, and persistent supply chain disruptions. These factors contribute to uncertainty in the pace of economic recovery, particularly for low-income countries, Small Island developing states (SIDS), and least developed countries (LDCs). Moreover, the existential risks related to climate change, especially for small island states, are escalating rapidly. It is crucial to have effective long-term financing and investment strategies to steer global development in the right direction and address the increasingly complex global challenges we face. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations provide one pathway for countries to channel capital towards achieving SDG outcomes more effectively.

During the 2022 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), the Commonwealth Secretariat’s mandate to enhance and expand technical support for development financing was reaffirmed. The outcome of the CHOGM, as outlined in Communique Outcome 39, offers an opportunity to explore various activities and provide technical assistance related to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) aspects for member states.

39. Heads recognised the crucial role of investment in transforming economies and creating inclusive economic growth and long-term prosperity. They acknowledged that high quality investment and infrastructure, both digital and physical, and notably clean, green infrastructure investment, is a cornerstone of sustainable economic growth.

Within the Commonwealth, numerous prominent international finance hubs and stock exchanges contribute to private sector Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives. These include cities like London, Singapore, Toronto, Melbourne, Mumbai, Cape Town, Mauritius, The Bahamas, Kigali, Nairobi, and Lagos. There is an opportunity for regulators and countries to exchange policy experiences as they develop their own sustainable investment and policy frameworks that align with their specific contexts. Commonwealth nations would benefit from formulating strategies to incorporate ESG factors into their institutional and legal frameworks for sovereign debt management. This would encompass various aspects of back, middle, and front-office activities, including funding and issuance strategies, investor relations programs, debt management practices, and reporting transparency. By implementing such strategies, governments can establish actionable plans that connect sovereign debt to impactful ESG outcomes, while also diversifying and expanding their investor base.

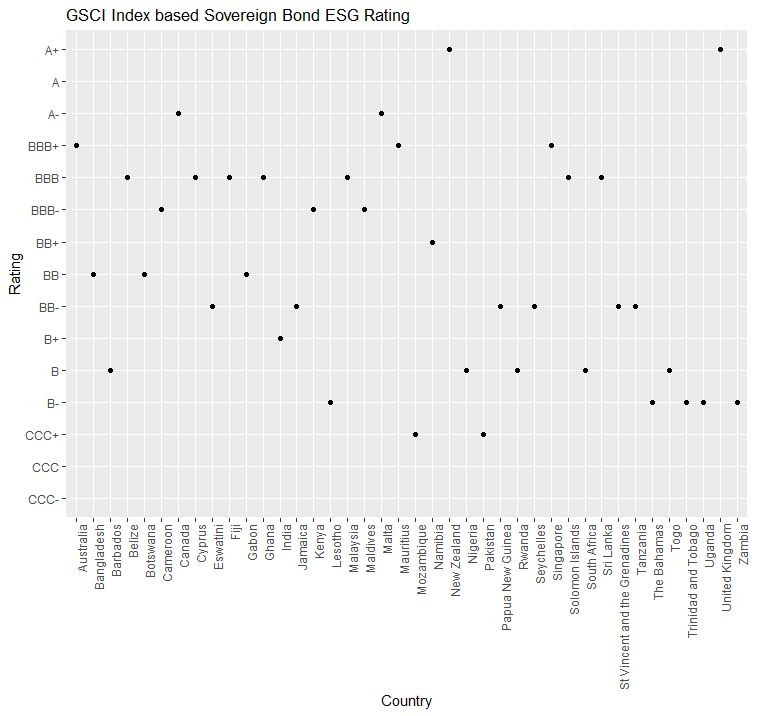

In Figure 1, based on SolAbility’s Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index ESG Rating of Sovereign Bonds, the Commonwealth nations’ ratings have been compiled and displayed to showcase that Commonwealth nations vary widely depending on each member nations’ separate policies and level of prioritisation of ESG parameters.

Enhancing capacity and providing training on ESG concepts, risks, and opportunities could be extended at both the national and subnational levels. This would assist in aligning with standards set by International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and improving sustainability and performance in the public sector, especially in achieving Net Zero targets. Moreover, fostering collaboration among Commonwealth countries for regular discussions and the development of ESG strategies would facilitate knowledge exchange, data sharing, and the establishment of coherence amidst the variety of methodologies and definitions currently in circulation. Supporting the creation of sustainable finance taxonomies and implementing regulations for carbon disclosure would be advantageous, aiming to avoid market fragmentation and inconsistent regulatory approaches.

To address the challenge of limited reporting and sustainability data, the creation of additional research toolkits and country trackers could be explored. These resources would enable benchmarking, monitoring, and expediting progress in sustainable investing at the country level. As the concept of ESG continues to expand, it holds the potential to support governments, businesses, communities, and individuals in collaboratively fostering a socially and environmentally responsible economy and society, while prioritising the protection of our planet.

Sources

Baker, B. (2023). ESG investing statistics 2023. Bankrate. https://www.bankrate.com/investing/esg-investing-statistics/#stats

Deloitte (n.d.) #1 What is ESG? https://www2.deloitte.com/ce/en/pages/global-business-services/articles/esg-explained-1-what-is-esg.html

Diligent Insights. (n.d.). What is ESG? An Environmental, Social and Governance Guide – https://www.diligent.com/insights/esg/

International Finance Corporation. (2005). Who Cares Wins: 2005 Conference Report [PDF]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/9d9bb80d-625d-49d5-baad-8e46a0445b12/WhoCaresWins_2005ConferenceReport.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=jkD172p

Morris, I. (2023, February 27). ESG Investing: The Past, Present, and Future. Govenda. https://www.govenda.com/blog/esg-investing-past-present-future

Peterdy, K. (2023, May 30). ESG (Environmental, Social, & Governance). Corporate Finance Institute. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/esg/esg-environmental-social-governance/

SolAbility (2022, September 14). Sovereign bonds & sustainability. https://solability.com/solability/the-global-sustainable-competitiveness-index/sovereign-bonds-sustainability

The Commonwealth Secretariat (2023, April 20). ESG Practices for Value Creation in the Commonwealth https://www.thecommonwealth-ilibrary.org/index.php/comsec/catalog/view/1104/1103/9707